Section 2.6 — Inventory of continuous distributions#

This notebook contains all the code examples from Section 2.6 Inventory of continuous distributions of the No Bullshit Guide to Statistics.

Notebook setup#

# Ensure required Python modules are installed

%pip install --quiet numpy scipy seaborn ministats

Note: you may need to restart the kernel to use updated packages.

# load Python modules

import numpy as np

import seaborn as sns

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from ministats import plot_pdf

from ministats import plot_cdf

from ministats import plot_pdf_and_cdf

# Figures setup

plt.clf() # needed otherwise `sns.set_theme` doesn't work

sns.set_theme(

context="paper",

style="whitegrid",

palette="colorblind",

rc={"font.family": "serif",

"font.serif": ["Palatino", "DejaVu Serif", "serif"],

"figure.figsize": (6,2)},

)

%config InlineBackend.figure_format = "retina"

<Figure size 640x480 with 0 Axes>

# Simple float __repr__

import numpy as np

if int(np.__version__.split(".")[0]) >= 2:

np.set_printoptions(legacy='1.25')

# Set random seed for repeatability

np.random.seed(42)

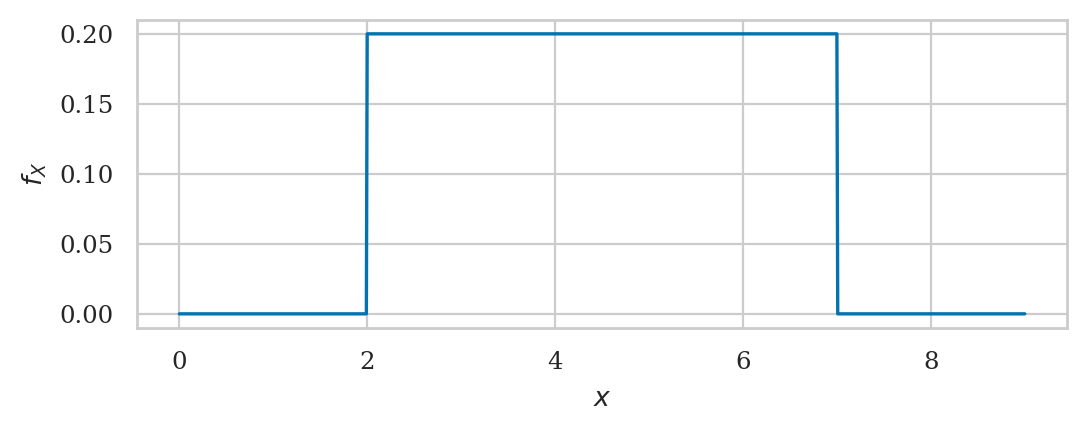

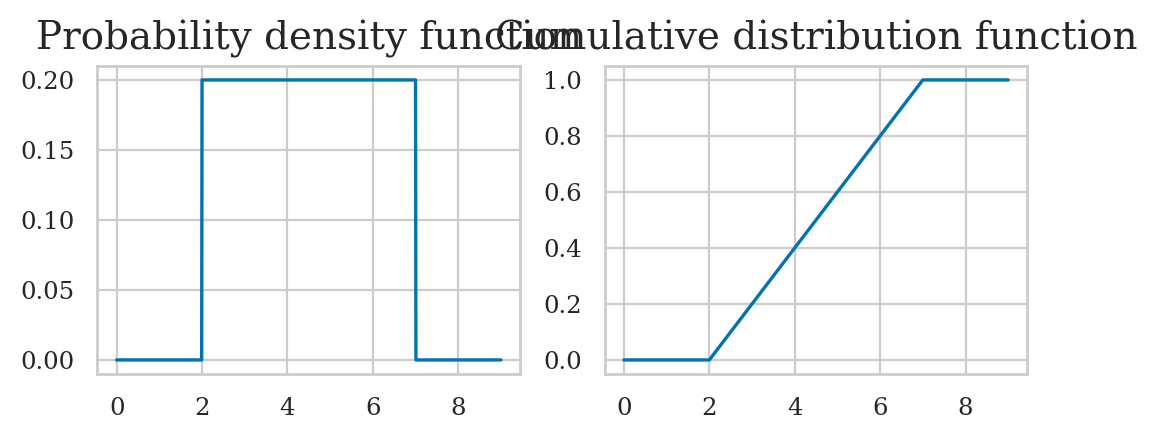

Uniform distribution#

The uniform distribution \(\mathcal{U}(\alpha,\beta)\) is described by the following probability density function:

For a uniform distribution \(\mathcal{U}(\alpha,\beta)\), each \(x\) between \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) is equally likely to occur, and values of \(x\) outside this range have zero probability of occurring.

from scipy.stats import uniform

alpha = 2

beta = 7

rvU = uniform(alpha, beta-alpha)

# draw 10 random samples from X

rvU.rvs(10)

array([3.87270059, 6.75357153, 5.65996971, 4.99329242, 2.7800932 ,

2.7799726 , 2.29041806, 6.33088073, 5.00557506, 5.54036289])

# # ALT. use sns.lineplot

# # plot the probability density function (pdf) of the random variable X

# xs = np.linspace(0, 10, 1000)

# fUs = rvU.pdf(xs)

# sns.lineplot(x=xs, y=fUs)

Cumulative distribution function#

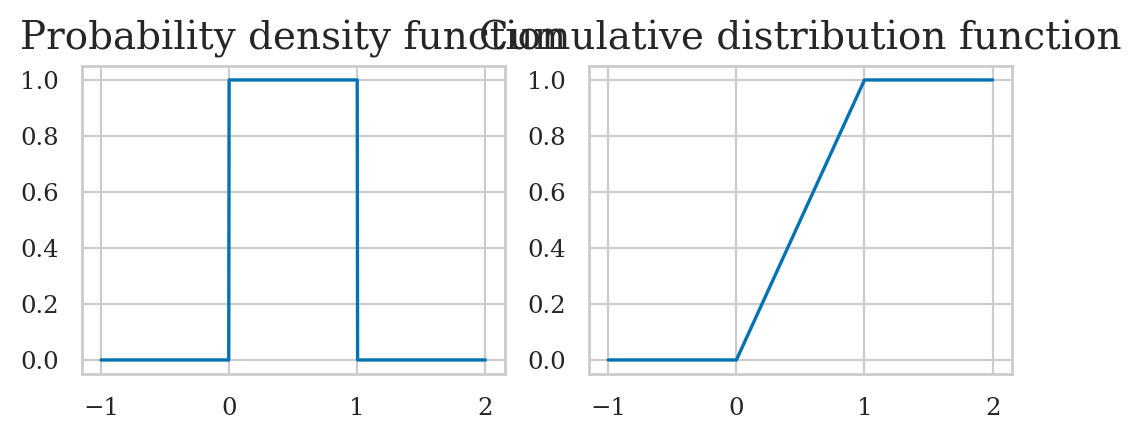

Standard uniform distribution#

The standard uniform distribution \(U_s \sim \mathcal{U}(0,1)\) is described by the following probability density function:

where \(U\) is the name of the random variable and \(u\) are particular values it can take on.

The above equation describes tells you how likely it is to observe \(\{U_s=x\}\). For a uniform distribution \(\mathcal{U}(0,1)\), each \(x\) between 0 and 1 is equally likely to occur, and values of \(x\) outside this range have zero probability of occurring.

from scipy.stats import uniform

rvUs = uniform(0, 1)

# draw 10 random samples from X

rvUs.rvs(1)

array([0.02058449])

import random

random.seed(3)

random.random()

0.23796462709189137

random.uniform(0,1)

0.5442292252959519

import numpy as np

np.random.seed(42)

np.random.rand(10)

array([0.37454012, 0.95071431, 0.73199394, 0.59865848, 0.15601864,

0.15599452, 0.05808361, 0.86617615, 0.60111501, 0.70807258])

Simulating other random variables#

We can use the uniform random variable to generate random variables from other distributions.

For example,

suppose we want to generate observations of a coin toss random variable

which comes out heads 50% of the time and tails 50% of the time.

We can use the standard uniform random variables obtained from random.random()

and split the outcomes at the “halfway point” of the sample space,

to generate the 50-50 randomness of a coin toss.

The function flip_coin defined below shows how to do this:

def flip_coin():

u = random.random() # random number in [0,1]

if u < 0.5:

return "heads"

else:

return "tails"

# simulate one coin toss

flip_coin()

'heads'

# simulate 10 coin tosses

[flip_coin() for i in range(0,10)]

['tails',

'tails',

'heads',

'heads',

'tails',

'heads',

'heads',

'tails',

'heads',

'tails']

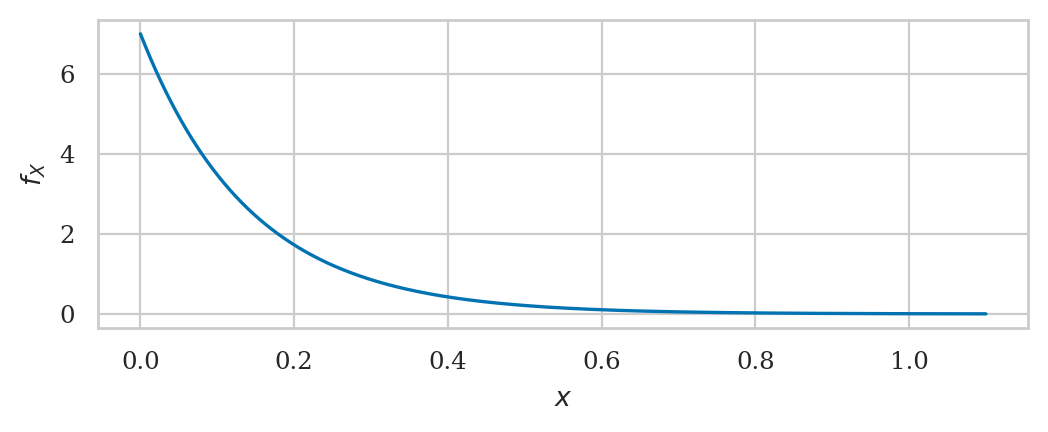

Exponential distribution#

from scipy.stats import expon

lam = 7

rvE = expon(loc=0, scale=1/lam)

To create the model rvE,

we had to specify a location parameter loc,

which we set to zero,

and a scale parameter,

which we set to the inverse of the rate parameter \(\lambda = \texttt{lam}\).

The location parameter can be used to shift the exponential distribution to the right,

but we set loc=0 to get the simple case that corresponds to the un-shifted distribution \(\textrm{Expon}(\lambda)\).

rvE.mean(), rvE.var()

(0.14285714285714285, 0.02040816326530612)

# math formulas for mean and var

1/lam, 1/lam**2

(0.14285714285714285, 0.02040816326530612)

## ALT. we can obtain mean and ver using the .stats() method

## The code below also computes the skewness and the kurtosis

# mean, var, skew, kurt = rvE.stats(moments='mvsk')

# mean, var, skew, kurt

# f_E(5) = pdf value at x=10

rvE.pdf(0.2)

1.7261787475912451

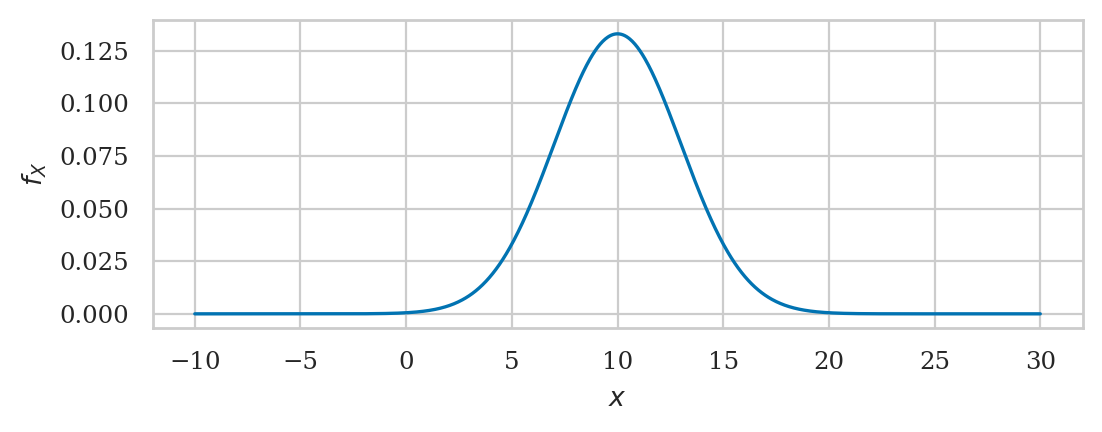

Normal distribution#

A random variable \(N\) with a normal distribution \(\mathcal{N}(\mu,\sigma)\) is described by the probability density function:

The mean \(\mu\) and the standard deviation \(\sigma\) are called the parameters of the distribution. The math notation \(\mathcal{N}(\mu, \sigma)\) is used to describe the whole family of normal probability distributions.

from scipy.stats import norm

mu = 10 # = 𝜇 where is the centre?

sigma = 3 # = 𝜎 how spread out is it?

rvN = norm(mu, sigma)

rvN.mean(), rvN.var()

(10.0, 9.0)

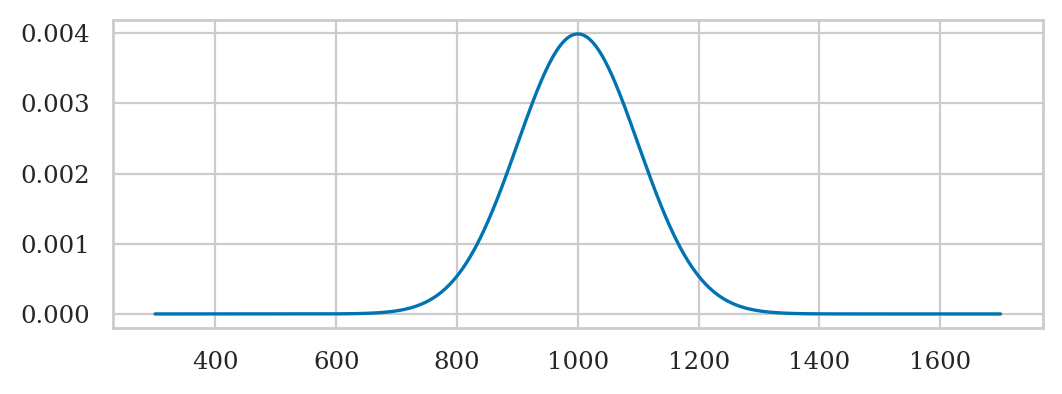

# ALT. generate the plot manually

# create a normal random variable

from scipy.stats import norm

mean = 1000 # 𝜇 (mu) = where is its center?

std = 100 # 𝜎 (sigma) = how spread out is it?

rvN = norm(mean, std)

# plot its probability density function (pdf)

xs = np.linspace(300, 1700, 1000)

ys = rvN.pdf(xs)

ax = sns.lineplot(x=xs, y=ys)

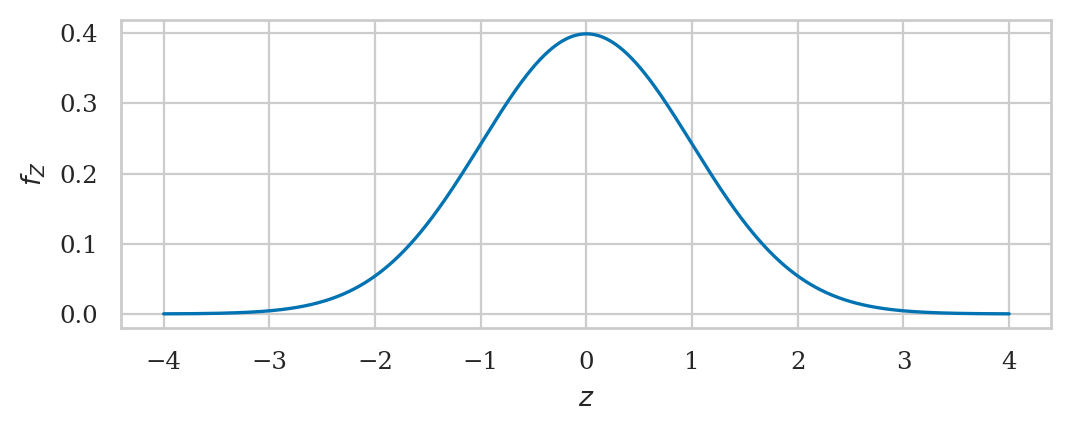

Standard normal distribution#

A standard normal is denoted \(Z\) with a normal distribution \(\mathcal{N}(\mu=0,\sigma=1)\) and described by the probability density function:

from scipy.stats import norm

rvZ = norm(0,1)

rvZ.mean(), rvZ.var()

(0.0, 1.0)

Cumulative probabilities in the tails#

Probability of \(Z\) being smaller than \(-2.2\).

rvZ.cdf(-2.3)

0.010724110021675809

Probability of \(Z\) being greater than \(2.2\).

1 - rvZ.cdf(2.3)

0.010724110021675837

Probability of \(|Z| > 2.2\).

rvZ.cdf(-2.3) + (1-rvZ.cdf(2.3))

0.021448220043351646

norm.cdf(-2.3,0,1) + (1-norm.cdf(2.3,0,1))

0.021448220043351646

Inverse cumulative distribution calculations#

rvZ.ppf(0.05)

-1.6448536269514729

rvZ.ppf(0.95)

1.6448536269514722

rvZ.interval(0.9)

(-1.6448536269514729, 1.6448536269514722)

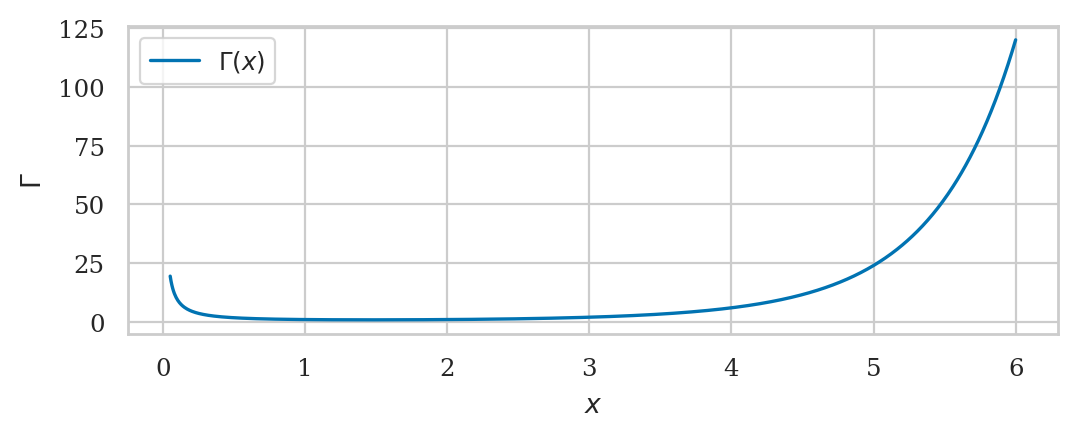

Mathematical interlude: the gamma function#

Gamma function#

from math import factorial

from scipy.special import gamma as gammaf

gammaf(1), factorial(0) # = 0! = 1

(1.0, 1)

gammaf(2), factorial(1) # = 1! = 1

(1.0, 1)

gammaf(3), factorial(2) # = 2! = 2*1

(2.0, 2)

gammaf(4), factorial(3) # = 3! = 3*2*1

(6.0, 6)

gammaf(5), factorial(4) # = 4! = 4*3*2*1

(24.0, 24)

gammaf(5.1)

27.93175373836837

factorial(4.1)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[47], line 1

----> 1 factorial(4.1)

TypeError: 'float' object cannot be interpreted as an integer

[gammaf(x) for x in [5, 5.1, 5.2, 5.5, 5.8, 5.9, 6]]

[24.0,

27.93175373836837,

32.578096050331354,

52.34277778455352,

85.6217375127053,

101.27019121310353,

120.0]

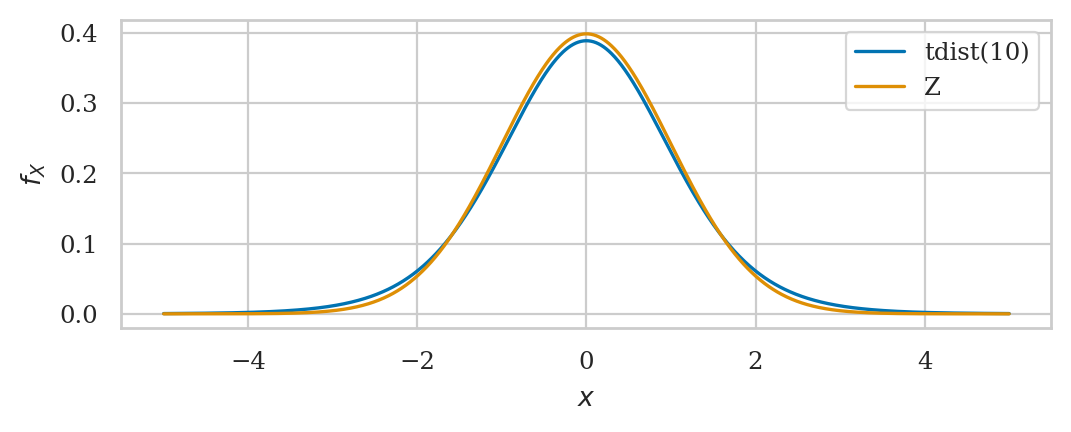

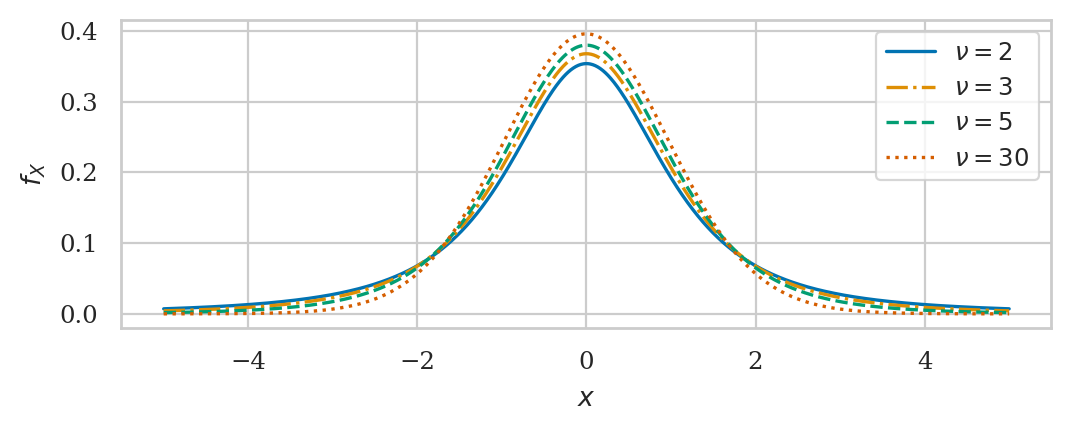

Student’s t-distribution#

This is a generalization of the standard normal with “heavy” tails.

from scipy.stats import t as tdist

rvT = tdist(df=10)

rvT.mean(), rvT.var()

(0.0, 1.25)

# Kurtosis formula kurt(rvT) = 6/(df-4) for df>4

rvT.stats("k")

1.0

rvT.cdf(-2.3)

0.022127156642143552

rvT.ppf(0.05), rvT.ppf(0.95)

(-1.8124611228107341, 1.8124611228107335)

Fisher–Snedecor’s F-distribution#

from scipy.stats import f as fdist

df1, df2 = 15, 10

rvF = fdist(df1, df2)

rvF.mean(), rvF.var()

(1.25, 0.7986111111111112)

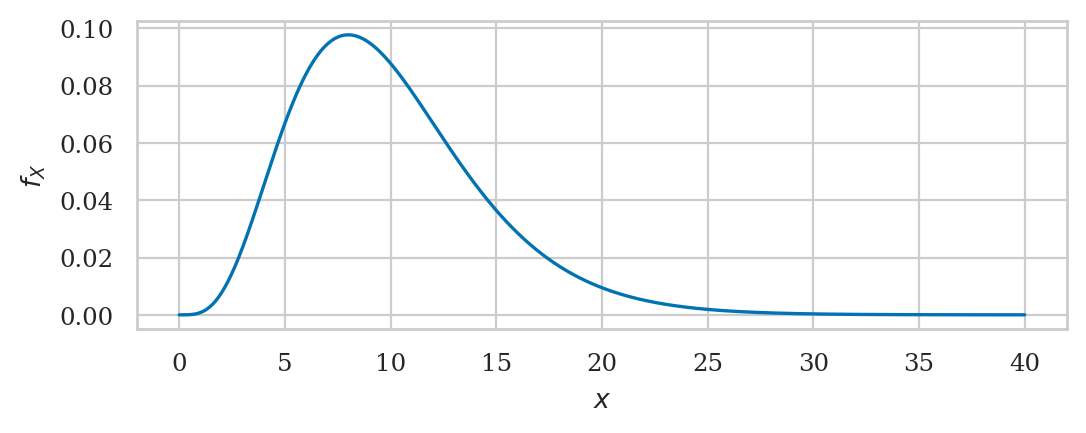

Chi-squared distribution#

from scipy.stats import chi2

df = 10

rvX2 = chi2(df)

rvX2.mean(), rvX2.var()

(10.0, 20.0)

1 - rvX2.cdf(20)

0.02925268807696113

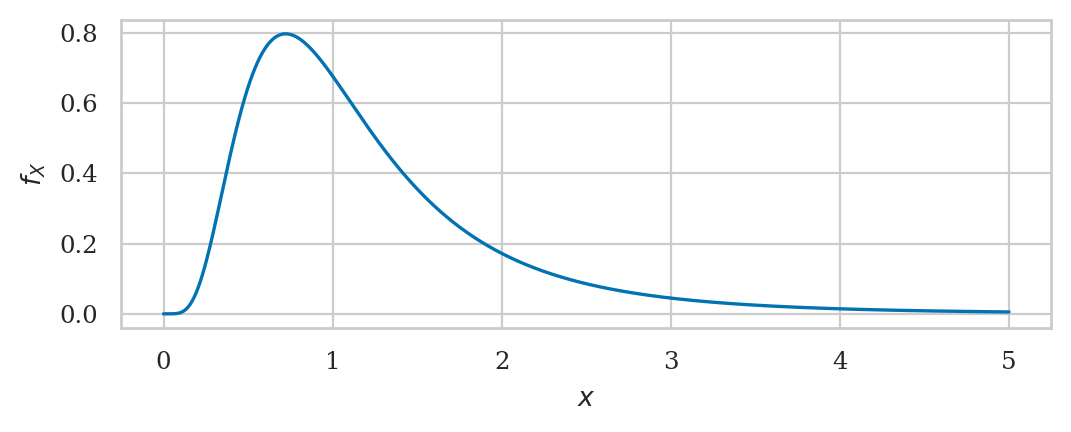

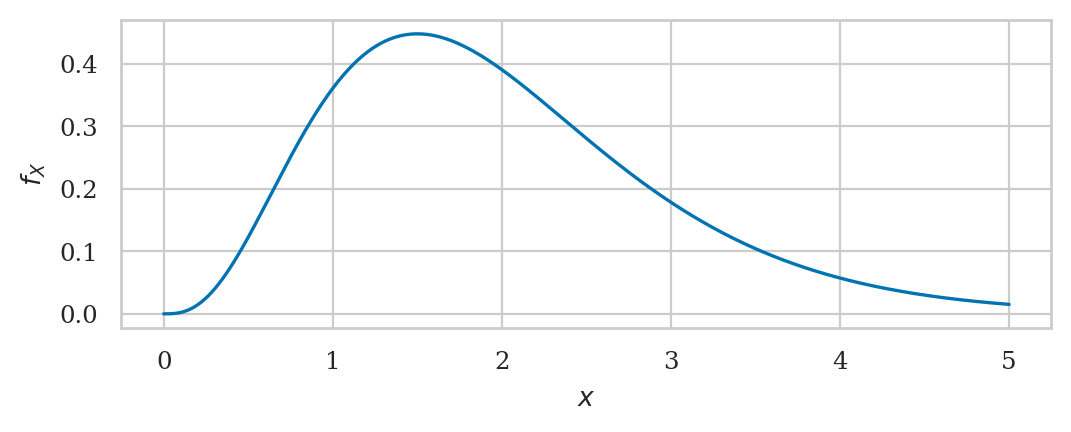

Gamma distribution#

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gamma_distribution

https://docs.scipy.org/doc/scipy/reference/generated/scipy.stats.gamma.html

from scipy.stats import gamma as gammadist

alpha = 4

loc = 0

lam = 2

beta = 1/lam

rvG = gammadist(alpha, loc, beta)

rvG.mean(), rvG.var()

(2.0, 1.0)

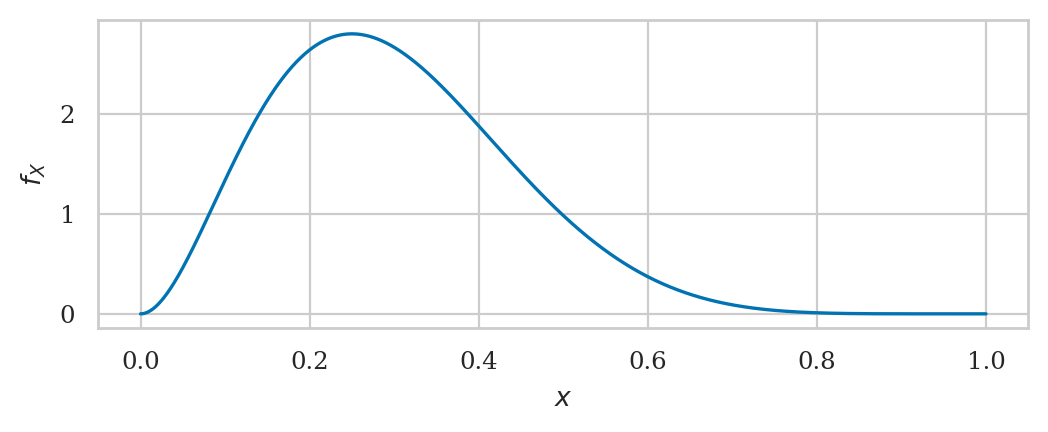

Beta distribution#

from scipy.stats import beta as betadist

alpha = 3

beta = 7

rvB = betadist(alpha, beta)

rvB.mean(), rvB.var()

(0.3, 0.019090909090909092)

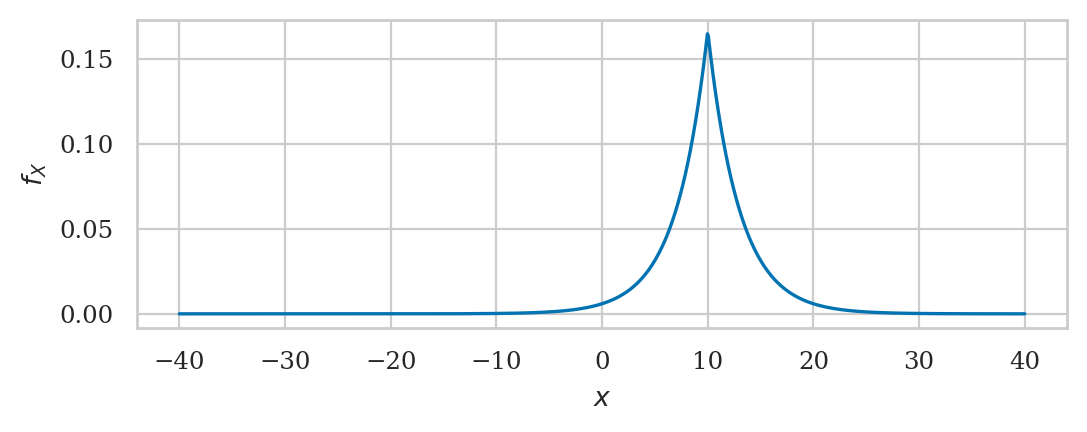

Laplace distribution#

from scipy.stats import laplace

mu = 10

b = 3

rvL = laplace(mu, b)

rvL.mean(), rvL.var()

(10.0, 18.0)

Explanations#

Location-scale families#

Normal location-scale family example#

Exam question 1:#

b = 109

muN = 100

sigmaN = 5

# standardize b

z_b = (b - muN) / sigmaN

z_b

1.8

from scipy.stats import norm

rvZ = norm(loc=0, scale=1)

1 - rvZ.cdf(z_b)

0.03593031911292577

Exam question 2:#

z_l = rvZ.ppf(0.05)

z_u = rvZ.ppf(0.95)

[sigmaN*z_l + muN, sigmaN*z_u + muN]

[91.77573186524263, 108.22426813475737]

Equivalent calculations using “custom” model#

b = 109

rvN = norm(loc=100, scale=5)

1 - rvN.cdf(b)

0.03593031911292577

[rvN.ppf(0.05), rvN.ppf(0.95)]

[91.77573186524263, 108.22426813475737]

Student’s t location-scale family#

b = 109

locS = 100

scaleS = 5

t_b = (b - locS) / scaleS

t_b

1.8

from scipy.stats import t as tdist

rvT = tdist(df=6, loc=0, scale=1)

1 - rvT.cdf(t_b)

0.06097621069194392

Equivalent calculations using “custom” model#

rvS = tdist(df=6, loc=100, scale=5)

1 - rvS.cdf(b)

0.06097621069194392

Uniform location-scale family#

locV = 100

scaleV = 20

b = 115

u_b = (b - locV) / scaleV

u_b

0.75

from scipy.stats import uniform

rvU = uniform(0, 1)

1 - rvU.cdf(u_b)

0.25

rvV = uniform(100, 20)

1 - rvV.cdf(115)

0.25

Chi-square scale family#

scaleS = 10

b = 150

q_b = 150 / scaleS

from scipy.stats import chi2

rvQ = chi2(df=7)

1 - rvQ.cdf(q_b)

0.03599940476342878

rvS = chi2(df=7, scale=10)

1 - rvS.cdf(150)

0.03599940476342878