Appendix F — Calculus tutorial#

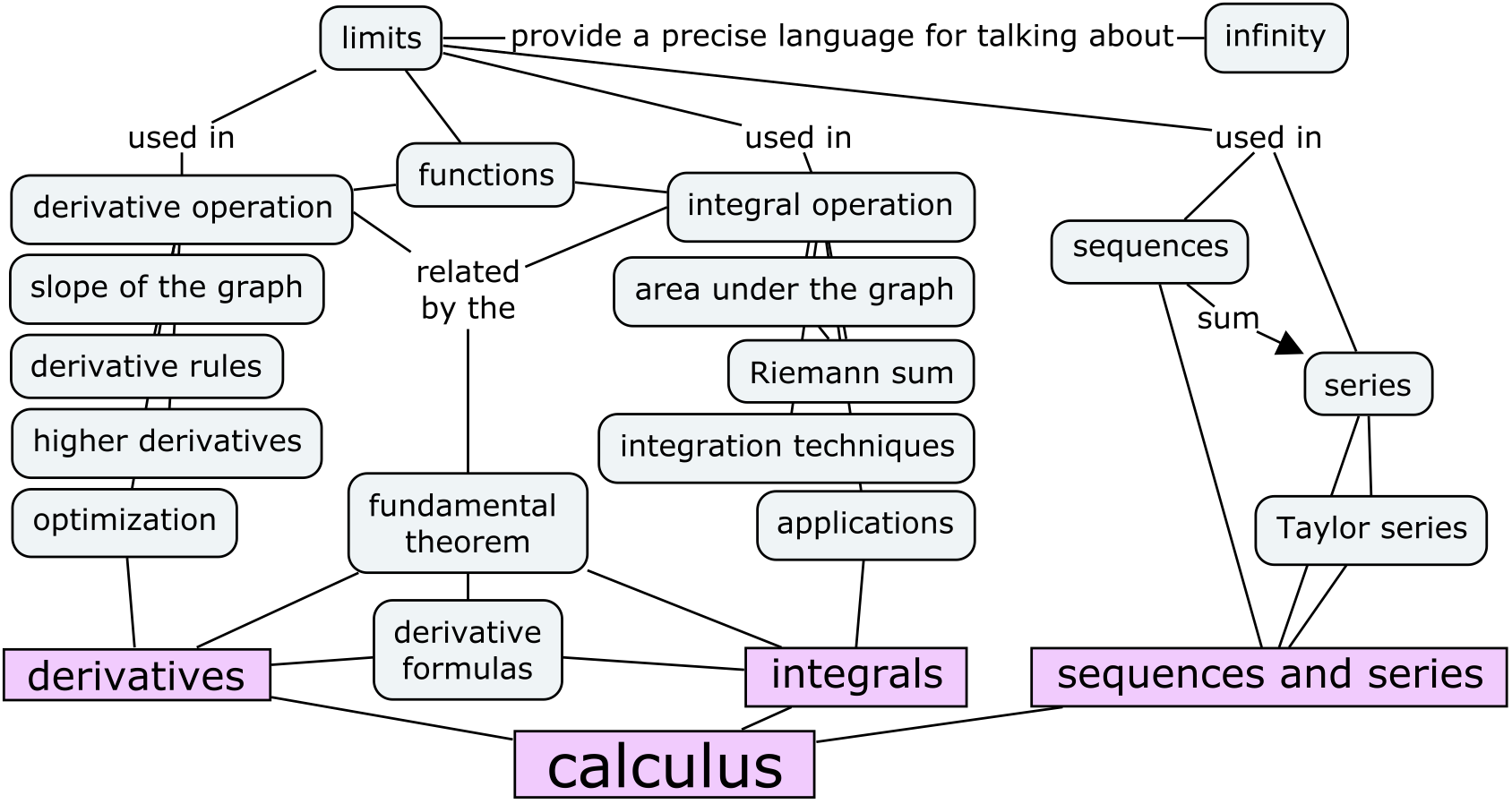

Calculus is the study of the properties of functions.

The operations of calculus are used to describe the limit behaviour of functions,

calculate their rates of change, and calculate the areas under their graphs.

In this section we’ll learn about the SymPy functions for calculating

limits, derivatives, integrals, and summations.

Click the binder button or this link

bit.ly/calctut3 to run this notebooks interactively.

Notebook setup#

%pip install --quiet sympy numpy scipy seaborn ministats

Note: you may need to restart the kernel to use updated packages.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import seaborn as sns

sns.set_theme(

context="paper",

style="whitegrid",

palette="colorblind",

rc={"font.family": "serif",

"font.serif": ["Palatino", "DejaVu Serif", "serif"],

"figure.figsize": (5, 1.7)},

)

%config InlineBackend.figure_format = 'retina'

# simple float __repr__

np.set_printoptions(legacy='1.25')

from sympy import init_printing

init_printing()

Introduction#

Example: car trip#

Suppose you’re driving to see a friend in a neighbouring town. The total length of the journey is 27000 m (27 km) along a straight road. We can describe your position over time as a function \(x(t)\), and use the car’s trip odometer to measure the distance travelled. Right before you leave, which we’ll call \(t=0\), you reset the trip odometer so it reads \(x(0)=0\) m.

Velocity#

The derivative function \(x^{\prime\!}(t)\), pronounced “\(x\) prime,” describes how the function \(x(t)\) changes over time. In this example \(x^{\prime\!}(t)\) is the car’s velocity. If your current velocity is \(x^{\prime\!}(t)=15\) m/s, then the car’s position \(x(t)\) is increasing by \(15\) m each second. If you maintain this velocity, the position will increase at a constant rate: \(x(0)=0\) m, \(x(1)=15\) m, \(x(2)=30\) m, and so on until \(t=1800\) s when you’ll have travelled \(1800\times 15 = 27000\) m and reached your destination.

To estimate the time remaining in the trip, assuming the velocity \(x^{\prime\!}(t)\) stays constant, you can divide the remaining distance by the current velocity: $\(\text{time remaining at } t \; \; =\; \frac{ 27000 - x(t) }{ x^{\prime\!}(t) } \;\;\; \textrm{s}.\)\( The bigger the derivative \)x^{\prime!}(t)$, the faster you’ll arrive. If you drive two times faster, the time remaining will be halved.

Inverse problem#

Imagine that the car’s odometer is busted and you don’t have any way to measure the distance \(x(t)\) you have travelled over time. The car’s speedometer is still working though, so you know the velocity \(x^{\prime\!}(t)\) at all times. Is there a way to calculate the distance travelled using only the information from the speedometer?

There is! You can infer the position at time \(t\) from the velocity \(x^{\prime\!}(t)\). Think about it—if the speedometer reports \(x^{\prime\!}(t)=15\) m/s, then you know that the car’s position is increasing at the rate of \(15\) m each second. We can describe the total distance travelled until time \(t=\tau\) (the Greek letter tau) as the integral of the velocity function \(x^{\prime\!}(t)\) between \(t=0\) and \(t=\tau\): $\(x(\tau) \; = \; \int_{t=0}^{t=\tau} x^{\prime\!}(t)\, dt.\)\( The integral symbol \)\int\( is an elongated \)S\( that stands for *sum*. To calculate the total distance travelled, we imagine splitting the time between \)t=0\( and \)t=\tau\( into many short time intervals \)dt\(. During each instant, the position increases by \)x^{\prime!}(t)dt\( m, where \)x^{\prime!}(t)\( is the velocity (measured in m/s), and \)dt\( is the time interval (measured in seconds). The integral \)\int_{0}^{\tau} x^{\prime!}(t), dt\( calculates the "sum" of these \)x^{\prime!}(t),dt\( contributions accumulated between \)t=0\( and \)t=\tau$.

The situation described in the car example shows that calculus concepts are not theoretical constructs reserved only for math specialists, but common ideas you encounter every day. The derivative \(q^{\prime\!}(t)\) describes the rate of change of the quantity \(q(t)\). The integral \(\int_a^b q(t)dt\) measures the total accumulation of the quantity \(q(t)\) during the time period from \(t=a\) to \(t=b\).

Doing calculus: then and now#

Symbolic calculations using pen and paper#

The pen-and-paper approach is a good way to learn calculus, because manipulating math symbols “by hand” develops your intuitive understanding of calculus procedures. Writing math on paper allows you to use high-level abstractions and arrive at exact symbolic answers.

Symbolic calculations using SymPy#

The Python library SymPy allows you to do symbolic math calculations on a computer.

%pip install -q sympy

Note: you may need to restart the kernel to use updated packages.

import sympy as sp

# define symbolic variable x

x = sp.symbols("x")

The symbols function creates SymPy symbolic variables.

Unlike ordinary Python variables that hold a particular value,

SymPy variables act as placeholders that can take on any value.

We can use the symbolic variables to create expressions,

just like we do with math variables in pen-and-paper calculations.

expr = 4 - x**2

expr

sp.factor(expr)

You can also substitute a particular <value> for the variable \(\tt{x}\)

into the expression expr by calling the method expr.subs()

and passing in a python dictionary object {x:<value>}.

expr.subs({x:1})

We can also also ask SymPy to solve the equation expr = 0,

which means to find the values of \(x\) that satisfy the equation \(4 - x^2 = 0\).

sp.solve(expr, x)

The function solve is the main workhorse in SymPy. This incredibly

powerful function knows how to solve all kinds of equations. In fact

solve can solve pretty much any equation! When high school students

learn about this function, they get really angry—why did they spend

five years of their life learning to solve various equations by hand,

when all along there was this solve thing that could do all the math

for them? Don’t worry, learning math is never a waste of time.

The function solve takes two arguments. Use solve(expr,var) to

solve the equation expr==0 for the variable var. You can rewrite any

equation in the form expr==0 by moving all the terms to one side

of the equation; the solutions to \(A(x) = B(x)\) are the same as the

solutions to \(A(x) - B(x) = 0\).

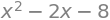

For example, to solve the quadratic equation \(x^2 + 2x - 8 = 0\), use

sp.solve(x**2 + 2*x - 8, x)

In this case the equation has two solutions so solve returns a list.

Check that \(x = 2\) and \(x = -4\) satisfy the equation \(x^2 + 2x - 8 = 0\).

Simplify any math expression

sp.simplify(5*x - 3*x + 42)

sp.expand( (x-4)*(x+2) )

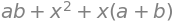

Collect the terms in expression that contain different powers of x.

a, b, c = sp.symbols("a b c")

sp.collect(x**2 + x*b + a*x + a*b, x)

Numerical computing using NumPy#

The Python library NumPy makes it easy to do numerical calculations on a computer.

%pip install -q numpy

Note: you may need to restart the kernel to use updated packages.

import numpy as np

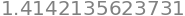

Compute an approximation to \(\sqrt{2}\).

np.sqrt(2)

Create an array of numbers manually.

np.array([1.0, 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.4, 1.5])

array([1. , 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.4, 1.5])

Create the same array by calling the linspace function,

with starting point, end point, and number of steps.

np.linspace(1.0, 1.5, 6)

array([1. , 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.4, 1.5])

xs = np.linspace(0, 2, 11)

xs

array([0. , 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1. , 1.2, 1.4, 1.6, 1.8, 2. ])

def h(x):

return 4 - x**2

fhs = h(xs)

fhs

array([4. , 3.96, 3.84, 3.64, 3.36, 3. , 2.56, 2.04, 1.44, 0.76, 0. ])

Scientific computing using SciPy#

The Python module SciPy is a toolbox of scientific computing helper functions. For example, computing the integral of the function \(h(x) = 4 - x^2\) between \(x=0\) and \(x=2\) requires only a few lines of code:

%pip install -q scipy

Note: you may need to restart the kernel to use updated packages.

from scipy.integrate import quad

quad(h, 0, 2)[0]

Applications of calculus#

We use calculus concepts to describe various quantities in physics, chemistry, biology, engineering, machine learning, business, economics and other domains where quantitative analysis is used. Many laws of nature are expressed in terms of derivatives and integrals, so it’s essential that you learn the language of calculus if you want to study science.

Math prerequisites#

Sets notation#

S = {1, 2, 3}

T = {3, 4, 5, 6}

The statement \(x \in S\) means \(x\) is one of the elements of the set \(S\).

In Python, we can use the in statement to check if a value is inside the set.

1 in S

True

The in statement returns False for a value that are not in the set.

7 in S

False

Set operations#

print("S ∪ T =", S.union(T))

print("S ∩ T =", S.intersection(T))

print("S \\ T =", S.difference(T))

S ∪ T = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}

S ∩ T = {3}

S \ T = {1, 2}

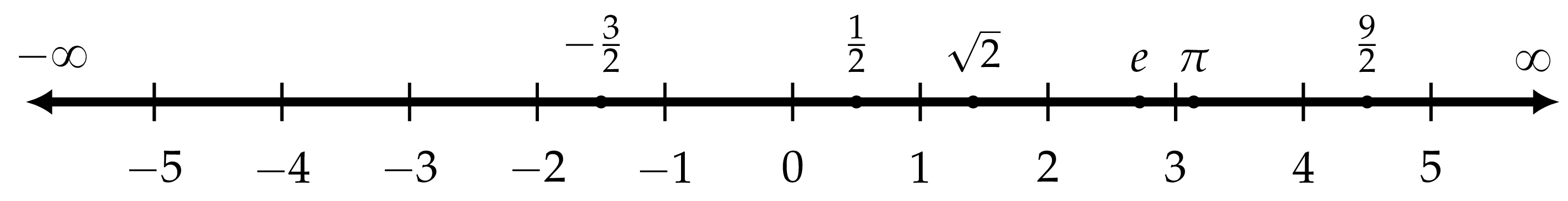

The number line#

Infinity#

The math symbol \(\infty\) describes the concept of infinity. We use the symbol \(\infty\) to represent an infinitely large quantity, that is greater than any number you can think of. Geometrically speaking, we can imagine the number line extends to the right forever towards infinity, as illustrated in the number line figure above. The number line also extends forever to the left, which we denote as negative infinity \(-\infty\).

Infinity is not a number but a process. When we use the symbol \(+\infty\), we’re describing the process of moving to the right on the number line forever. We go past larger and larger positive numbers and never stop.

Infinity is a key concept in calculus, so it’s important that we develop a precise language to talk about infinitely large numbers and procedures with an infinite number of steps, which we’ll do in the section on limits.

Functions#

In Python, we define functions using the def keyword.

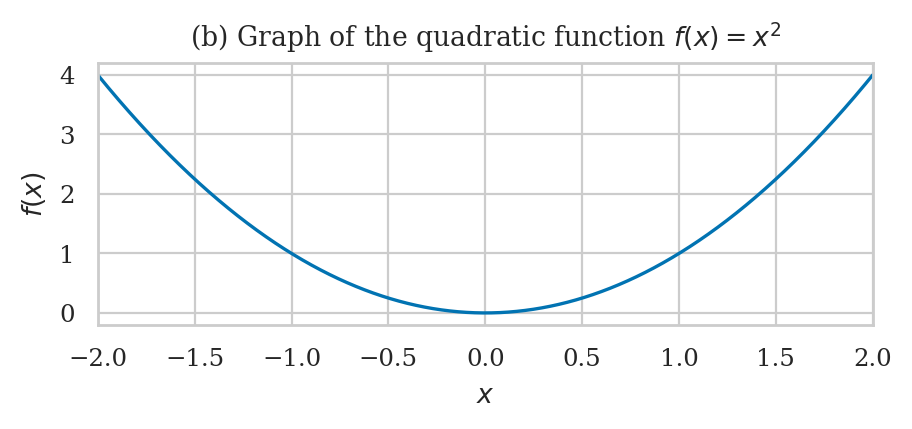

For example, the code cell below defines the function \(f(x) = x^2\), then evaluate it for the input \(x=3\).

# define the function f that takes input x

def f(x):

return x**2

# calling the function g on input x=4

f(3)

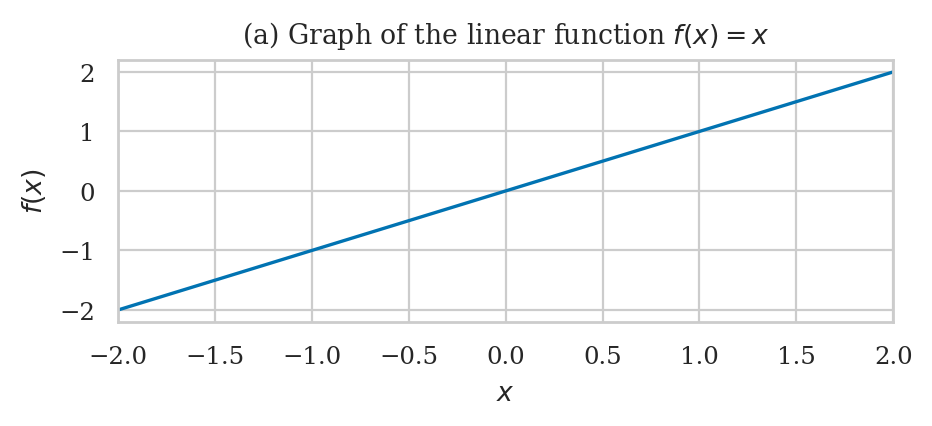

Function graphs#

The graph of the function \(f(x)\) is obtained by plotting a curve that passes through the set of input-output coordinate pairs \((x, f(x))\).

import numpy as np

xs = np.linspace(-3, 3, 1000)

fxs = f(xs)

The function linspace(-3,3,1000) creates an array of 1000 points in the interval \([-3,3]\).

We store this sequence of inputs into the variable xs.

Next, we computer the output value \(f(x)\) for each of the inputs in the array xs,

and store the result in the array fxs.

We can now use the function sns.lineplot() to generate the plot.

The helper function plot_func(f, xlim=[-3,3]) produces the same output.

Inverse functions#

The inverse function \(f^{-1}\) performs the \emph{inverse operation} of the function \(f\). If you start from some \(x\), apply \(f\), then apply \(f^{-1}\), you’ll arrive—full circle—back to the original input \(x\):

The inverse of the function \(f(x) = x^2\) is the function \(f^{-1}(x) = \sqrt{x}\). Earlier we computed \(f(3) = 9\). If we apply the inverse function to \(9\), we get \(f^{-1}(9) = \sqrt{9} = 3\).

from math import sqrt

sqrt(9)

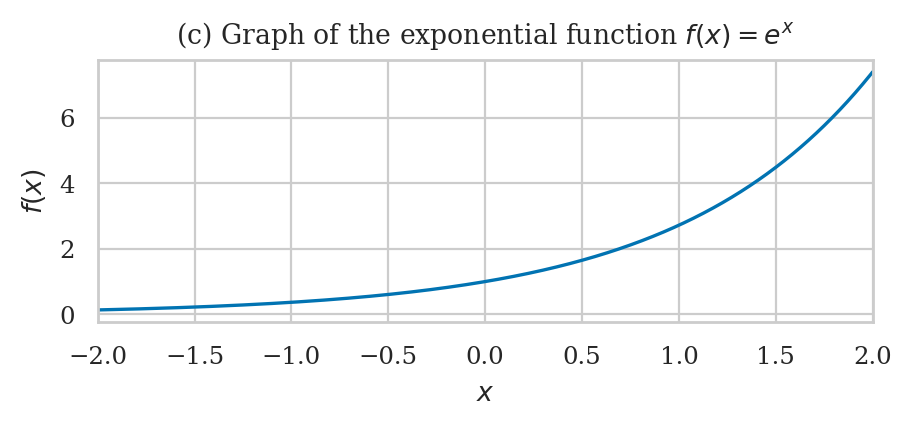

Another important pair of functions are the exponential function \(e^x\) and logarithmic functions \(\log(x)\). The logarithmic function \(\log(x)\) is the inverse of the exponential function \(e^x\), and vice versa. If if we compute the exponential function of a number, then apply the logarithmic function, we get back the original input.

from math import exp, log

log(exp(5))

exp(log(4))

Function properties#

We use the notation \(f \colon A \to B\) to denote a function from the input set \(A\) to the output set \(B\).

\(A\) is the domain of \(f\): the set of allowed inputs of the function.

\(B\) is the image of \(f\): the set of possible outputs of the function.

For example, the domain of the function \(f(x) = x^2\) is \(\mathbb{R}\) (any real number) and its image is \(\mathbb{R}_+\) (nonnegative real numbers), so we say \(f\) is a function of the form \(f \colon \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}_+\).

Function inventory#

Constant function#

Linear function#

Quadratic function#

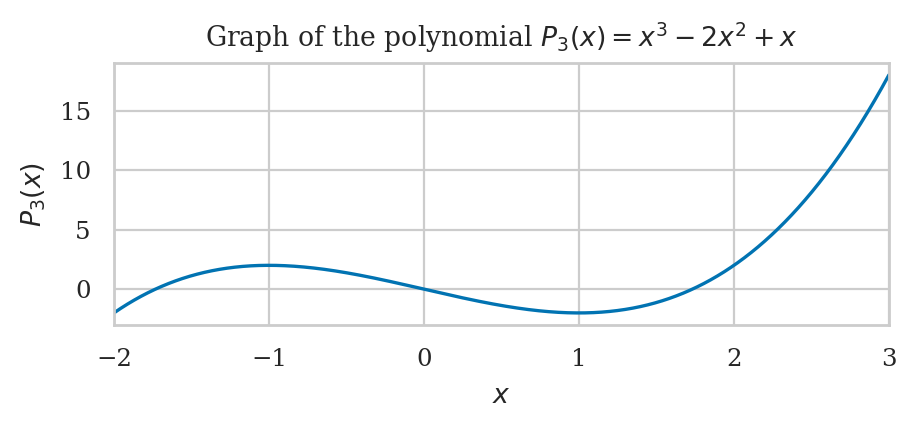

Polynomial functions#

Exponential function#

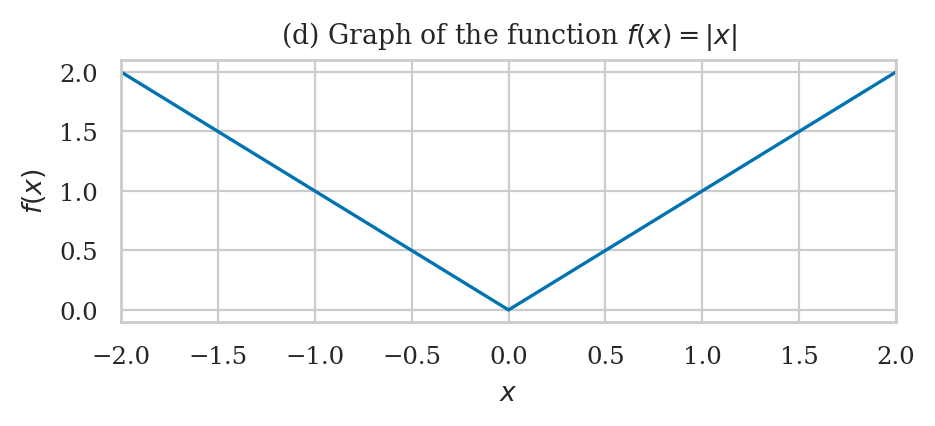

Absolute value function#

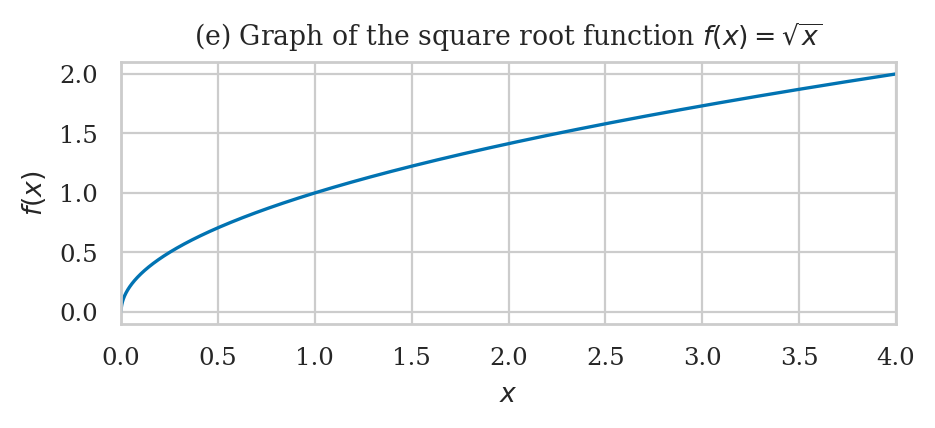

Square root function#

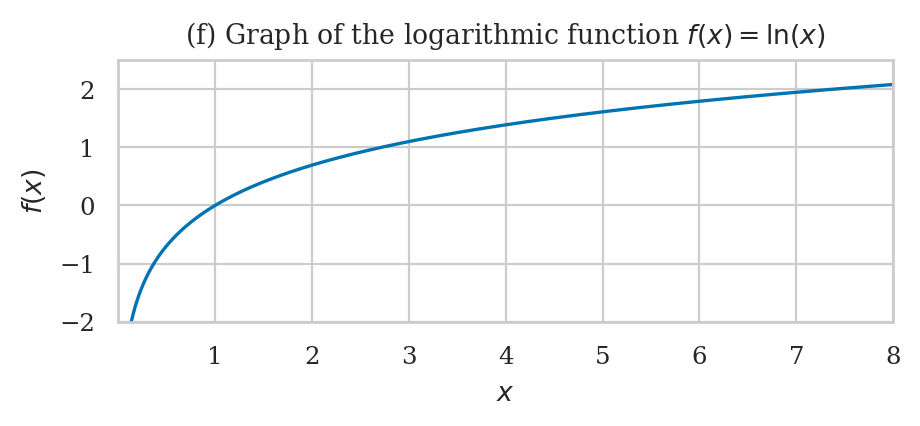

Logarithmic function#

Functions with discrete inputs#

Later in this tutorial, we’ll study functions with discrete inputs, \(a_k : \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{R}\), which are called sequences. We often express sequences by writing explicitly the first few values the sequence \([a_0, a_1, a_2, a_3, \ldots]\), which correspond to evaluating \(a_k\) for \(k=0\), \(k=1\), \(k=2\), \(k=3\), etc.

Geometry of rectangles and triangles#

The area of a rectangle of base \(b\) and height \(h\) is \(A = bh\).

The area of a triangle is equal to \(\frac{1}{2}\) times the length of its base \(b\) times its height \(h\): \(A = \tfrac{1}{2} b h\).

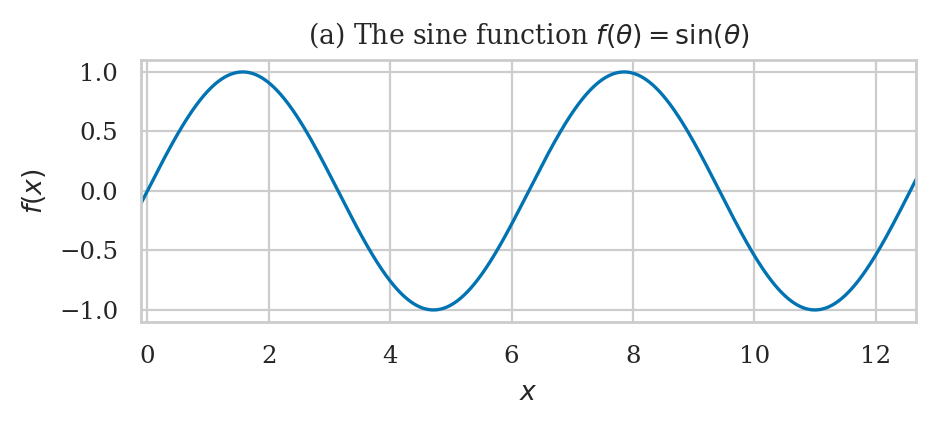

Trigonometric functions#

Sine function#

The trigonometric functions sin and cos take inputs in radians:

sp.sin(sp.pi/6)

For angles in degrees, you need a conversion factor of \(\frac{\pi}{180}\)[rad/\(^\circ\)]:

sp.sin(30*sp.pi/180) # 30 deg = pi/6 rads

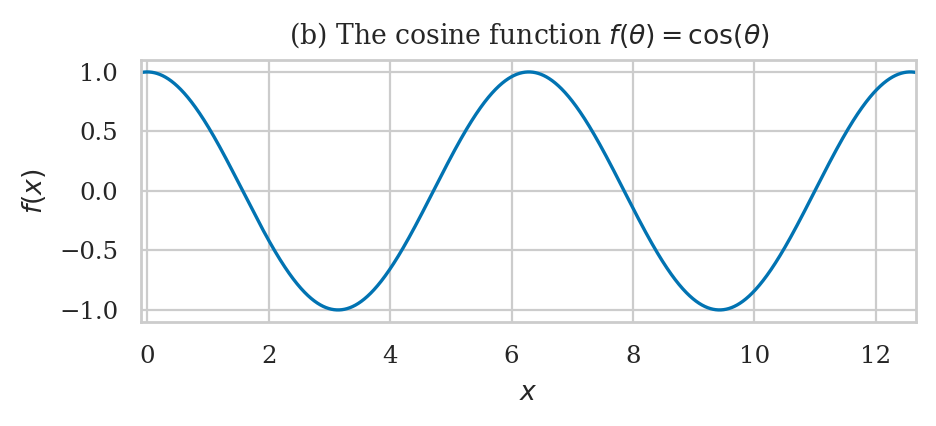

Cosine function#

sp.cos(sp.pi/6)

Overview and a look ahead#

Limits#

We use limits to describe, with mathematical precision, infinitely large quantities, infinitely small quantities, and procedures with infinitely many steps.

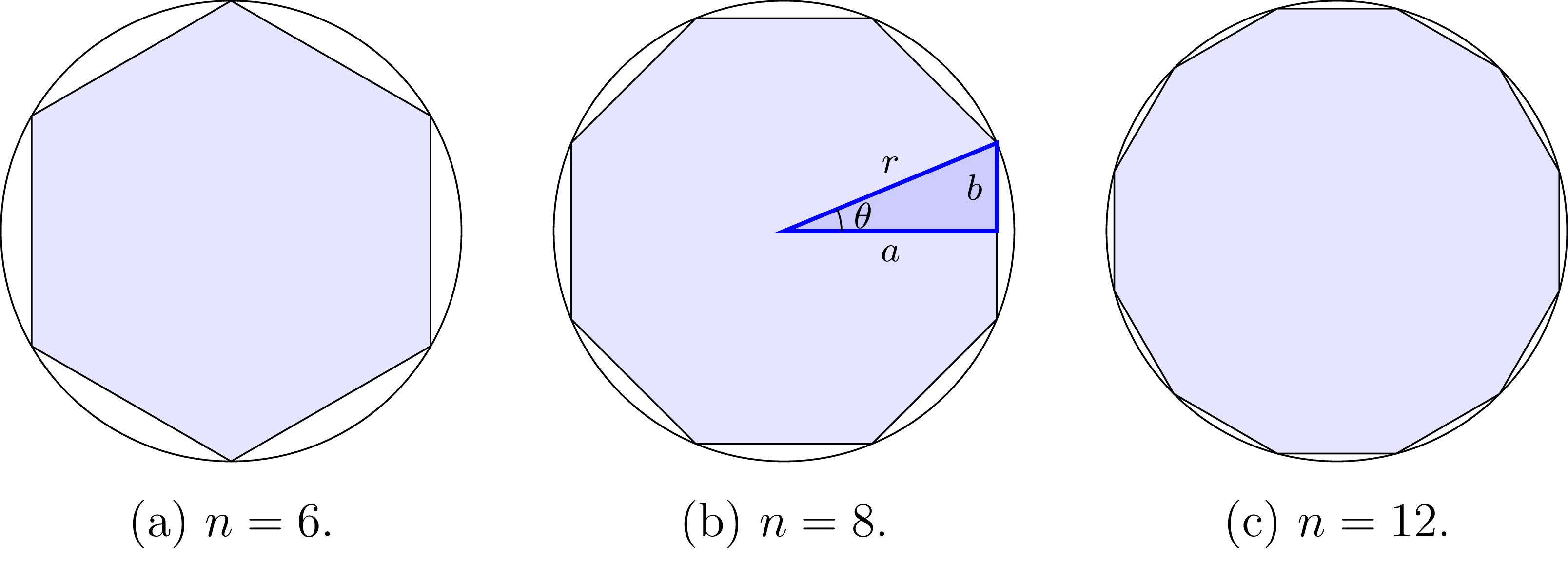

Example 1: Archimedes’ approximation to \(\pi\)#

Suppose we want to calculate the area of a circle of radius \(r=1\). Today we know the formula for the are of the circle is \(A_{\circ} = \pi r^2\), so the area of a circle with radius \(r=1\) is \(\pi\), but let’s suppose that you don’t know the formula.

Sometime around 250 BCE, Archimedes of Syracuse came up with clever idea was to approximate the circle as a regular polygon with \(n\) sides inscribed in the circle. The figure below shows the hexagonal (6-sides), octagonal (8-sides), and dodecagonal (12-sides) approximations to the circle.

Part (b) of the figure highlights one of the \(16\) identical triangular slices in the case when \(n=8\). The hypotenuse of this triangle has length \(r\), the angle \(\theta\) is \(\frac{360\circ}{16} = \frac{2\pi}{16} = \frac{\pi}{8}\)[rad], and its sides have length \(a=r\cos(\frac{\pi}{8})\) and \(b=r\sin(\frac{\pi}{8})\).

More generally, if we Consider a polygon with \(n\) sides inscribed in inside of a circle of radius \(r\). The total area of the polygon with \(n\) sides is:

The \(n\)-sided-polygon approximation to the area of the circle becomes more and more accurate as \(n\) grows. Here is the code that computes the approximations to the area of a circle with polygons with more and more sides.

import math

def calc_area(n, r=1):

theta = 2 * math.pi / (2 * n)

a = r * math.cos(theta)

b = r * math.sin(theta)

area = 2 * n * a * b / 2

return area

for n in [6, 8, 12, 50, 100, 1000, 10000]:

area_n = calc_area(n)

error = area_n - math.pi

print(f"{n=}, {area_n=}, {error=}")

n=6, area_n=2.5980762113533156, error=-0.5435164422364775

n=8, area_n=2.8284271247461903, error=-0.3131655288436028

n=12, area_n=3.0, error=-0.14159265358979312

n=50, area_n=3.133330839107606, error=-0.008261814482187102

n=100, area_n=3.1395259764656687, error=-0.0020666771241244497

n=1000, area_n=3.141571982779476, error=-2.0670810317202637e-05

n=10000, area_n=3.1415924468812855, error=-2.067085076440378e-07

In the limit as \(n \to \infty\), the \(n\)-sided-polygon approximation to the area of the circle will becomes exactly equal to area

We can use SymPy to calculate the limit as \(n\) goes to infinity:

n, r = sp.symbols("n r")

A_n = n * r**2 * sp.cos(sp.pi/n) * sp.sin(sp.pi/n)

sp.limit(A_n, n, sp.oo)

The result is \(\pi r^2\), which is the formula for the area of a circle.

Example 2: Euler’s number#

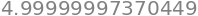

(1+1/2)**2

(1+1/3)**3

(1+1/4)**4

(1+1/12)**12

(1+1/365)**365

(1+1/1000)**1000

import sympy as sp

n = sp.symbols("n")

sp.limit( (1+1/n)**n, n, sp.oo).evalf()

Arithmetic operations with infinity#

The infinity symbol is denoted oo (two lowercase os) in SymPy. Infinity

is not a number but a process: the process of counting forever. Thus,

\(\infty + 1 = \infty\), \(\infty\) is greater than any finite number, and \(1/\infty\) is an

infinitely small number. Sympy knows how to correctly treat infinity

in expressions:

from sympy import oo

5000 < oo

oo + 1

1 / oo

Limits at infinity#

Limits are also useful to describe the behaviour of functions.

Example 3#

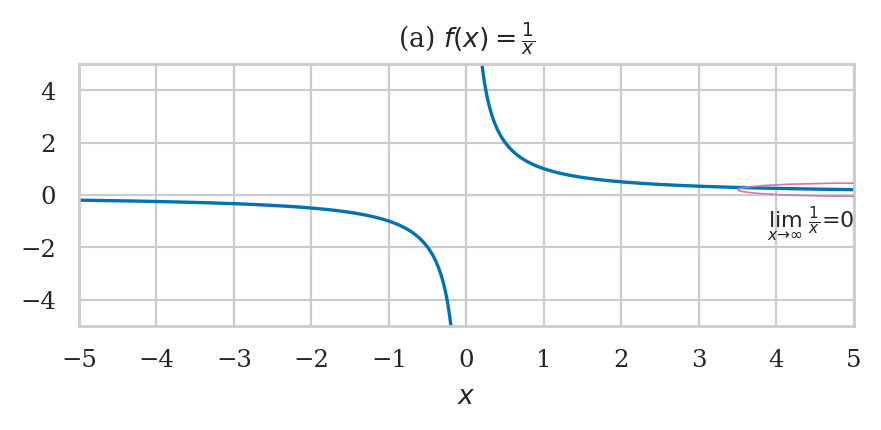

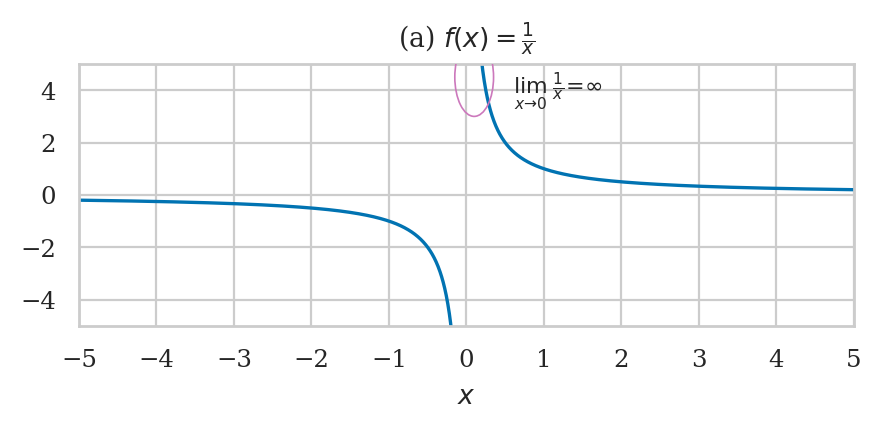

Consider the function \(f(x) = \frac{1}{x}\).

The limit command shows us what happens to \(f(x)\) as \(x\) goes to infinity:

As \(x\) becomes larger and larger, the fraction \(\frac{1}{x}\) becomes smaller and smaller. In the limit where \(x\) goes to infinity, \(\frac{1}{x}\) approaches zero: \(\lim_{x\to\infty}\frac{1}{x} = 0\).

from ministats.calculus import plot_limit

from ministats.calculus import plot_ellipse

# (a) Limits involving f(x) = 1/x

def finv(x):

return 1/x

ax = plot_limit(finv, xlim=[[-5,0],[0,5]], ylim=[-5,5])

ax.set_xticks([-5,-4,-3,-2,-1,0,1,2,3,4,5])

ax.set_xlabel("$x$")

ax.set_title(r"(a) $f(x) = \frac{1}{x}$")

# ellipse annotaiton x \to infty

plot_ellipse(ax, 5, 0.2, 3, 0.5, lx=5, ly=-1.1, ha="right",

label=r"$\lim_{x \to \infty}\; \frac{1}{x} = 0$");

Limit formulas#

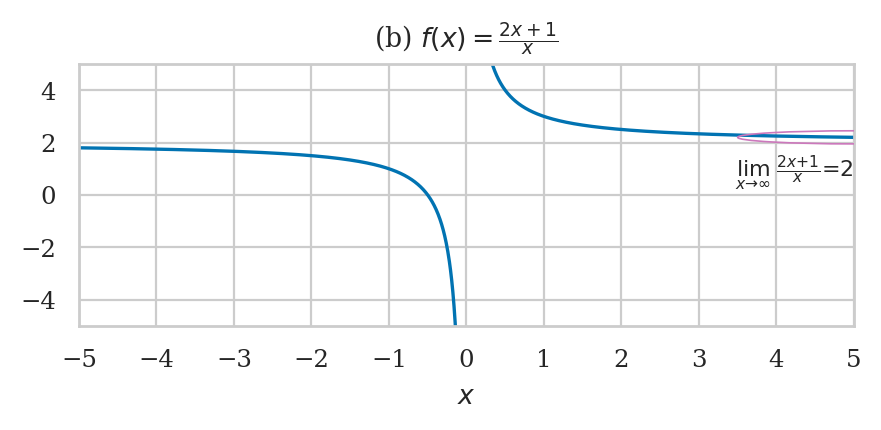

Example 4#

# (b) Limits involving f(x) = (2x+1)/x

def f2example(x):

return (2*x+1)/x

ax = plot_limit(f2example, xlim=[[-5,0],[0,5]], ylim=[-5,5])

ax.set_xticks([-5,-4,-3,-2,-1,0,1,2,3,4,5])

ax.set_xlabel("$x$")

ax.set_title("(b) $f(x) = \\frac{2x+1}{x}$")

# ellipse annotation x \to infty

plot_ellipse(ax, 5, 2.2, 3, 0.5, lx=5, ly=0.85, ha="right",

label=r"$\lim_{x \to \infty}\; \frac{2x+1}{x} = 2$");

Limit to zero#

Limit to a number#

Continuity#

Example 5#

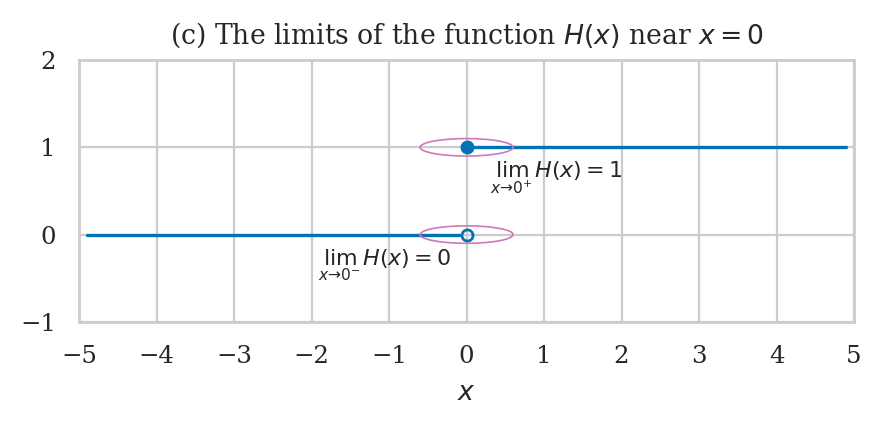

# (c) Limits involving the Heaviside step function f(x) = H(x)

def H(x):

if x >= 0:

return 1

else:

return 0

ax = plot_limit(H, xlim=[[-5,0],[0,5]], eps=0.1, ylim=[-1,2])

ax.set_xticks([-5,-4,-3,-2,-1,0,1,2,3,4,5])

ax.set_xlabel("$x$")

ax.set_title("(c) The limits of the function $H(x)$ near $x=0$")

# continuous point (filled circle)

ax.plot(0, 1, marker='o', markersize=4, color='C0')

# discontinuous point (open circle)

ax.plot(0, 0, marker='o', markersize=4, markerfacecolor='none', markeredgecolor='C0')

# ellipse annotation (from the left)

plot_ellipse(ax, 0, 0, 1.2, 0.2, lx=-0.2, ly=-0.35, ha="right",

label=r"$\lim_{x \to 0^-} H(x) = 0$")

# ellipse annotation (from the right)

plot_ellipse(ax, 0, 1, 1.2, 0.2, lx=0.3, ly=0.65,

label=r"$\lim_{x \to 0^+} H(x) = 1$");

Computing limits using SymPy#

import sympy as sp

Example 2 using SymPy#

The number \(e\) is defined as the limit \(e \equiv \lim_{n\to\infty}\left(1+\frac{1}{n}\right)^n\):

n = sp.symbols("n")

sp.limit((1+1/n)**n, n, sp.oo)

sp.limit((1+1/n)**n, n, sp.oo).evalf(40)

This limit expression describes the annual growth rate of a loan with a nominal interest rate of 100% and infinitely frequent compounding. Borrow \(\$1000\) in such a scheme, and you’ll owe \(\$2718.28\) after one year.

Example 3 using SymPy#

x = sp.symbols("x")

sp.limit(1/x, x, oo)

sp.limit(1/x, x, 0)

Example 4 using SymPy#

sp.limit((2*x+1)/x, x, sp.oo)

Example 5 using SymPy#

from sympy import Heaviside

sp.limit(Heaviside(x,1), x, 0, "-")

sp.limit(Heaviside(x,1), x, 0, "+")

Applications of limits#

Limits for derivatives#

The formal definition of a function’s derivative is expressed in terms of the rise-over-run formula for an infinitely short run:

We’ll continue the discussion of derivatives below.

Limit for integrals#

One way to approximate the area under the graph of the function \(f(x)\) between \(x=a\) and \(x=b\) is to split the area into \(n\) rectangular strips of width \(\Delta x = \frac{b-a}{n}\) and height \(f(x)\), and then calculate the sum of the areas of the rectangles:

We obtain the exact value of the area in the limit where we split the area into an infinite number of rectangles of infinitely small width:

Limits for series#

We use limits to describe the convergence properties of series. For example, the sum of the first \(n\) terms of the geometric series \(a_k= r^k\) corresponds to the following expression:

The series \(\sum a_k\) is defined as the limit \(n\to \infty\) of the above expression. When \(|r|<1\), the series converges to the a finite value:

In each of these domains, limit expressions will help us make precise statements that describe calculus procedures with infinite small lengths and infinite number of steps.

Derivatives#

The derivative function, denoted \(f'(x)\), \(\frac{d}{dx}f(x)\), \(\frac{df}{dx}\), or \(\frac{dy}{dx}\), describes the rate of change of the function \(f(x)\).

Let’s start by looking at slope calculations.

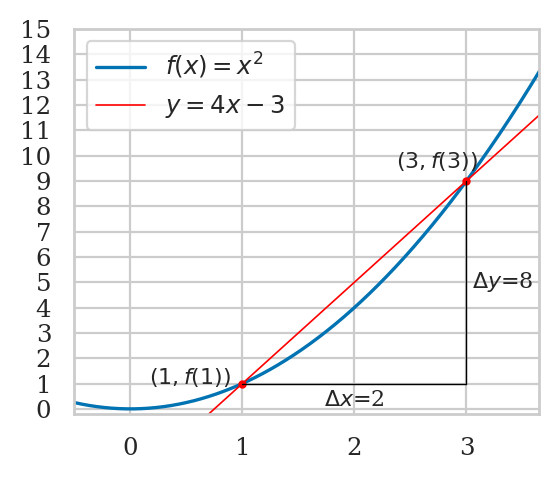

from ministats.calculus import plot_slope

def f(x):

return x**2

delta = 2

with plt.rc_context({"figure.figsize": (3,2.5)}):

ax = plot_slope(f, x=1, delta=delta, xlim=[-0.5,3.65], ylim=[-0.2, 12])

ax.set_xticks(range(0,4))

ax.set_yticks(range(0,16))

Numerical derivative calculations#

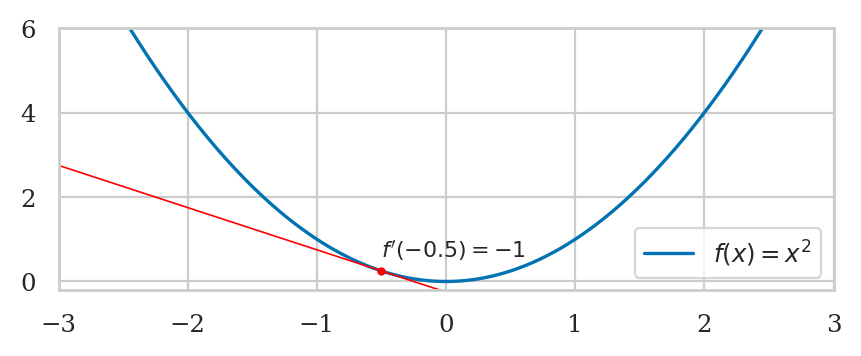

def differentiate(f, x, delta=1e-9):

"""

Compute the derivative of the function `f` at `x`

using a slope calculation for very short `delta`.

"""

df = f(x+delta) - f(x)

dx = (x + delta) - x

return df / dx

def f(x):

return x**2

differentiate(f, 1)

differentiate(f, -0.5)

Derivative formulas#

Derivative rules#

In addition to the table of derivative formulas, there are some important derivatives rules that allow you to find derivatives of composite functions.

Constant multiple rule#

The derivative of \(k\) times the function \(f(x)\) is equal to \(k\) times the derivative of \(f(x)\):

Sum rule#

The derivative of the sum of two functions is the sum of their derivatives:

Product rule#

The derivative of a product of two functions is the sum of two contributions:

In each term, the derivative of one of the functions is multiplied by the value of the other function.

Quotient rule#

This formula tells us how to obtain the derivative of a fraction of two functions:

Chain rule#

If you encounter a situation that includes an inner function and an outer function, like \(f(g(x))\), you can obtain the derivative by a two-step process:

In the first step, we leave the inner function \(g(x)\) alone and focus on taking the derivative of the outer function \(f(x)\). This step gives us \(f^{\prime\!}(g(x))\), which is the value of \(f^{\prime}\) evaluated at \(g(x)\). In the second step, we multiply this expression by the derivative of the inner function \(g^{\prime\!}(x)\).

Higher derivatives#

The second derivative of \(f(x)\) is denoted \(f^{\prime\prime\!}(x)\) or \(\frac{d^2f}{dx^2}\). It is obtained by applying the derivative operation to \(f(x)\) twice: \(\frac{d}{dx}\big[ \frac{d}{dx}[\tt{<f>}] \big]\).

Geometrically, the second derivative \(f^{\prime\prime\!}(x)\) tells us the curvature of \(f(x)\). Positive curvature means the function opens upward and looks like the bottom of a valley. The function \(f(x)=x^2\) has derivative \(f^{\prime\!}(x) = 2x\) and second derivative \(f^{\prime\prime\!}(x) = 2\), which means it has positive curvature. Negative curvature means the function opens downward and looks like a mountain peak. For example, the function \(g(x) = -x^2\) has negative curvature.

Examples#

We’ll use the SymPy function sp.diff to computes the derivative in the following examples.

Example 6#

x = sp.symbols("x")

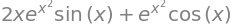

sp.diff(sp.exp(x**2), x)

Example 7#

sp.diff(sp.sin(x)*sp.exp(x**2), x)

Example 8#

sp.diff(sp.sin(x**2), x)

Computing derivatives using SymPy#

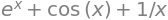

m, x, b = sp.symbols("m x b")

sp.diff(m*x + b, x)

x, n = sp.symbols("x n")

sp.simplify(sp.diff(x**n, x))

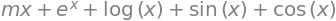

The exponential function \(f(x)=e^x\) is special because it is equal to its derivative:

from sympy import exp

sp.diff(exp(x), x)

from sympy import sqrt, exp, sin, log

sp.diff(exp(x) + sin(x) + log(x), x)

Applications of derivatives#

Tangent lines#

The tangent line to the function \(f(x)\) at \(x=x_0\) is the line that passes through the point \((x_0, f(x_0))\) and has the same slope as the function at that point. The tangent line to the function \(f(x)\) at the point \(x=x_0\) is described by the equation

What is the equation of the tangent line to \(f(x)=x^2\) at \(x_0=1\)?

fs = x**2

fs

dfsdx = sp.diff(fs, x)

dfsdx

a = 1

T_1 = fs.subs({x:a}) + dfsdx.subs({x:a})*(x - a)

T_1

Solving optimization problems using derivatives#

Optimization is about choosing an input for a function \(f(x)\) that results in the best value for \(f(x)\). The best value usually means the maximum value (if the function represents something desirable like profits) or the minimum value (if the function represents something undesirable like costs).

The derivative \(f'(x)\) encodes the information about the slope of \(f(x)\). Positive slope \(f'(x)>0\) means \(f(x)\) is increasing, negative slope \(f'(x)<0\) means \(f(x)\) is decreasing, and zero slope \(f'(x)=0\) means the graph of the function is horizontal. The critical points of a function \(f(x)\) are the solutions to the equation \(f'(x)=0\). Each critical point is a candidate to be either a maximum or a minimum of the function.

Analytical optimization using SymPy#

Example 9#

x = sp.symbols('x')

qx = (x - 5)**2

sp.diff(qx, x)

sols = sp.solve(sp.diff(qx,x), x)

sols # critical value

sp.diff(qx, x, 2).subs({x:sols[0]})

The second derivative is positive (bottom of a valley), so this means \(x^*_1 = 5\) is a minimum.

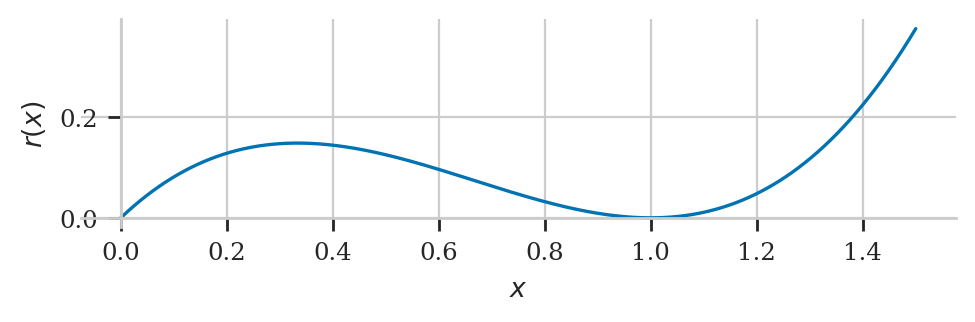

Example 10#

Let’s find the critical points of the function \(r(x)=x^3-2x^2+x\) and use the information from its second derivative to find the maximum of the function on the interval \(x \in [0,1]\).

x = sp.symbols('x')

rx = x**3 - 2*x**2 + x

sp.diff(rx, x).factor()

sols = sp.solve(sp.diff(rx,x), x)

sols # critical values

sp.diff(rx, x, 2).subs({x:sols[0]})

sp.diff(rx, x, 2).subs({x:sols[1]})

It we look at the graph of this function, we see the point \(x=\frac{1}{3}\) is a local maximum because it is a critical point of \(r(x)\) where the curvature is negative, meaning \(r(x)\) looks like the peak of a mountain at \(x=\frac{1}{3}\).

The point \(x=1\) is a local minimum because it is a critical point with positive curvature, meaning \(r(x)\) looks like the bottom of a valley at \(x=1\).

Numerical optimization#

def gradient_descent(f, x0=0, alpha=0.01, tol=1e-10):

"""

Find the minimum of the function `f` using gradient descent.

"""

current_x = x0

change = 1

while change > tol:

df_at_x = differentiate(f, current_x)

next_x = current_x - alpha * df_at_x

change = abs(next_x - current_x)

current_x = next_x

return current_x

Example 9 revisited#

def q(x):

return (x - 5)**2

gradient_descent(q, x0=10)

Example 10 revisited#

def r(x):

return x**3 - 2*x**2 + x

gradient_descent(r, x0=10)

Numerical optimization using SciPy#

Let’s now solve the same optimization problems from examples 9 and 10 using the function minimize from scipy.optimize.

from scipy.optimize import minimize

minimize(q, x0=10)["x"][0]

minimize(r, x0=10)["x"][0]

Integrals#

Act 1: Integrals as area calculations#

The integral of \(f(x)\) corresponds to the computation of the area under the graph of \(f(x)\). The area under \(f(x)\) between the points \(x=a\) and \(x=b\) is denoted as follows:

Properties of integrals#

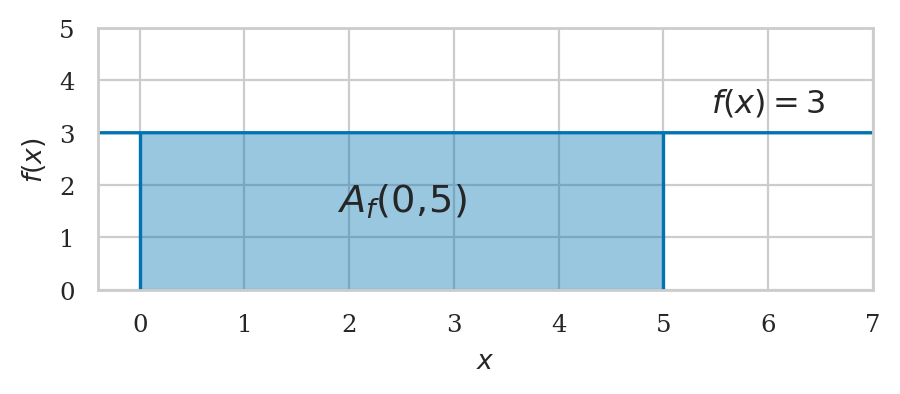

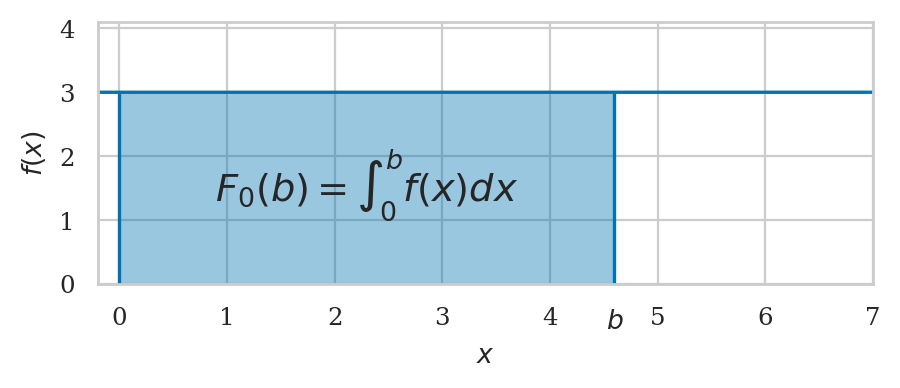

Example 11: integral of a constant function#

The following code shows the integral under \(f(x) = 3\) between \(a=0\) and \(b=5\).

def f(x):

return 3

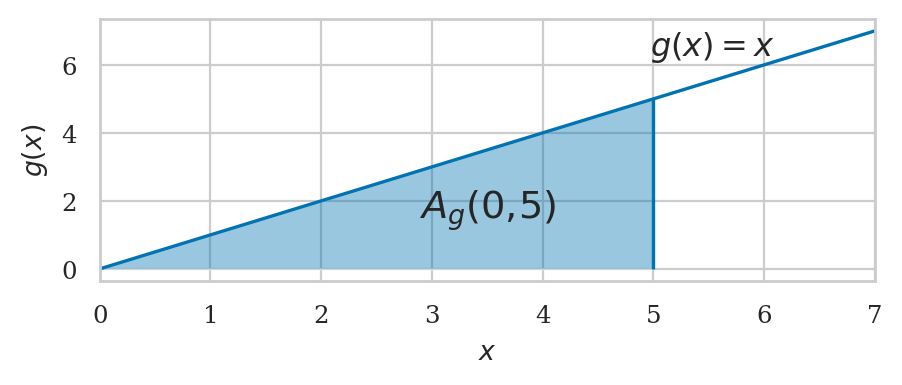

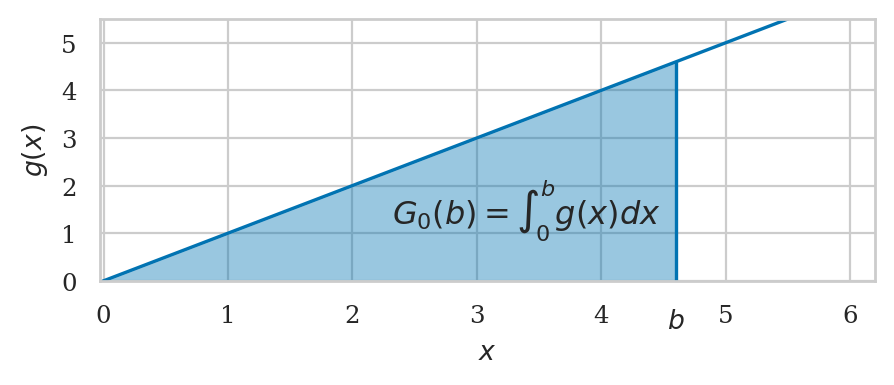

Example 12: integral of a linear function#

Let’s now plot the integral under \(g(x) = x\) between \(a=0\) and \(b=5\).

def g(x):

return x

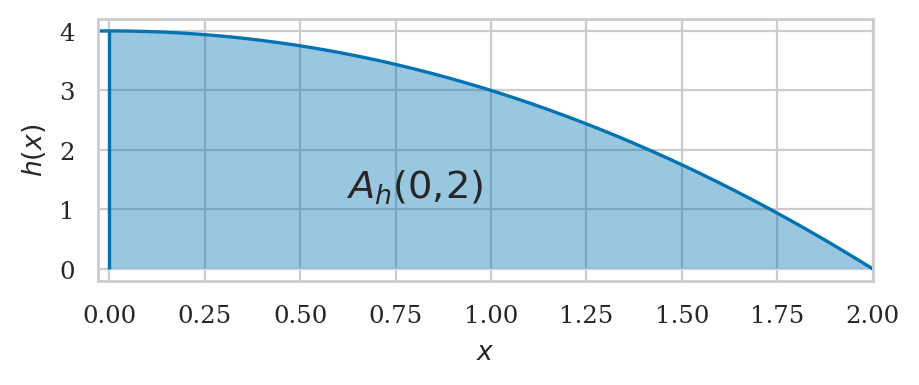

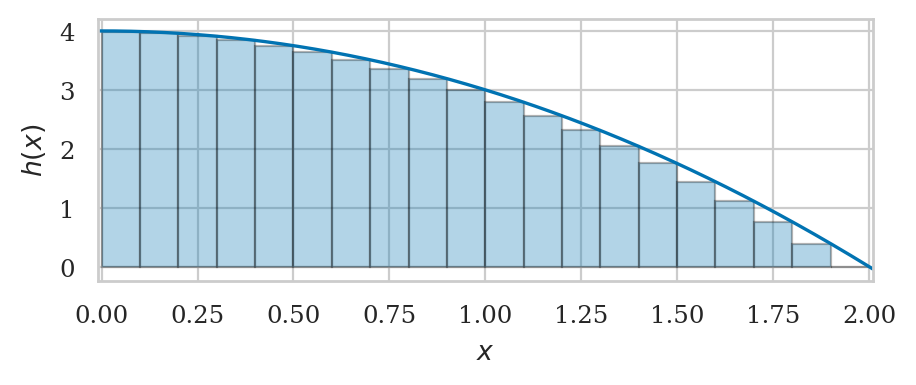

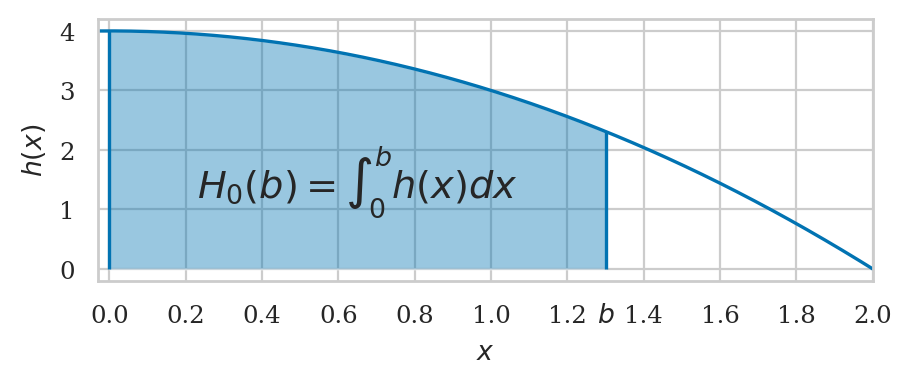

Example 13: integral of a polynomial#

def h(x):

return 4 - x**2

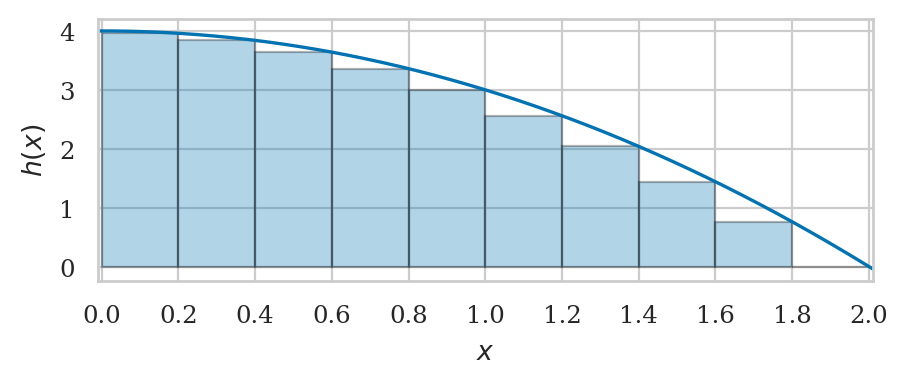

Computing integrals numerically#

Computing integral of \(f(x)\) “numerically” means we’re splitting the region of integration into many (think thousands or millions) of strips, computing the areas of these strips, then adding up the areas to obtain the total area under the graph of \(f(x)\). The approximation to the area under \(f(x)\) between \(x=a\) and \(x=b\) using \(n\) rectangular strips corresponds to the following formula:

where \(\Delta x = \frac{b-a}{n}\) is the width of the rectangular strips. The right endpoint of the \(k\)\textsuperscript{th} is located at \(x_k = a + k\Delta x\), so the height of the rectangular strips \(f(x_k)\) varies as \(k\) goes from between \(k=1\) (first strip) and \(k=n\) (last strip).

def integrate(f, a, b, n=10000):

"""

Computes the area under the graph of `f`

between `x=a` and `x=b` using `n` rectangles.

"""

dx = (b - a) / n # width of rectangular strips

xs = [a + k*dx for k in range(1,n+1)] # right-corners of the strips

fxs = [f(x) for x in xs] # heights of the strips

area = sum([fx*dx for fx in fxs]) # total area

return area

Example 13 continued#

def h(x):

return 4 - x**2

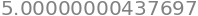

integrate(h, a=0, b=2, n=10)

from ministats.calculus import plot_riemann_sum

ax = plot_riemann_sum(h, a=0, b=2, xlim=[-0.01,2.01], n=10, flabel="h")

ax.set_xticks(np.arange(0,2.2,0.2));

integrate(h, a=0, b=2, n=20)

plot_riemann_sum(h, a=0, b=2, xlim=[-0.01,2.01], n=20, flabel="h");

integrate(h, a=0, b=2, n=50)

integrate(h, a=0, b=2, n=100)

integrate(h, a=0, b=2, n=1000)

integrate(h, a=0, b=2, n=10000)

integrate(h, a=0, b=2, n=1_000_000)

Example 11N#

We can also use integrate to compute the integral of the constant function \(f(x)=3\)

that we computed geometrically earlier.

def f(x):

return 3

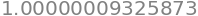

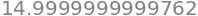

integrate(f, a=0, b=5, n=100000)

The numerical approximations we obtain is close to the exact answers \(\int_0^5 f(x)\,dx = 15\) we obtained earlier.

Example 12N#

Let’s now use integrate to compute the integral of the linear function \(g(x)=x\).

def g(x):

return x

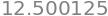

integrate(g, a=0, b=5, n=100000)

The numerical approximation is again close to the exact answers \(\int_0^5 g(x) \, dx = 12.5\).

Formal definition of the integral#

Riemann sum

As \(n\) goes to infinity…

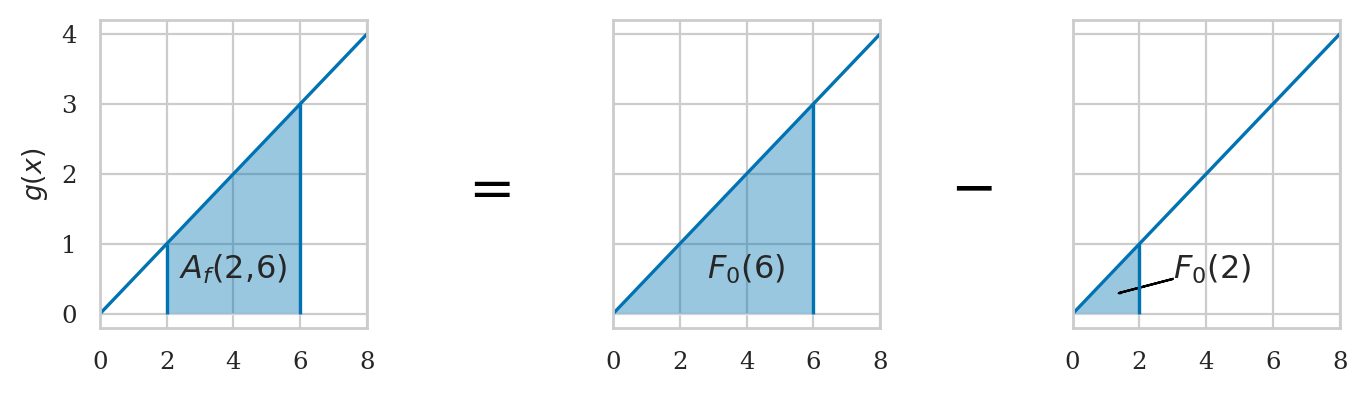

Act 2: Integrals as functions#

The integral function \(F\) corresponds to the area calculation as a function of the upper limit of integration:

The area under \(f(x)\) between \(x=a\) and \(x=b\) is obtained by calculating the change in the integral function:

In SymPy we use integrate(f, x) to obtain the integral function \(F(x)\) of any function \(f(x)\):

\(F_0(x) = \int_0^x f(u)\,du\).

from ministats.book.figures import integral_as_difference_in_G

integral_as_difference_in_G(flabel="f");

Example 11 revisited#

Example 12 revisited#

Example 13 revisited#

Act 3: Fundamental theorem of calculus#

The integral is the “inverse operation” of the derivative. If you perform the integral operation followed by the derivative operation on some function, you’ll obtain the same function:

x = sp.symbols("x")

fx = x**2

Fx = sp.integrate(fx, x)

Fx

sp.diff(Fx, x)

Alternately, if you compute the derivative of a function \(F(x)\) followed by the integral, you will obtain the original function (up to a constant):

Gx = x**3

dGdx = sp.diff(Gx, x)

dGdx

sp.integrate(dGdx, x)

Using antiderivatives to compute integrals#

The fundamental theorem of calculus gives us a symbolic trick for computing the integrals functions \(\int f(x)\,dx\) for many simple functions.

If you can find a function \(F(x)\) such that \(F'(x) = f(x)\), then the integral of \(f(x)\) is \(F(x)\) plus some constant:

Using derivative formulas in reverse#

fx = m + sp.exp(x) + 1/x + sp.cos(x) - sp.sin(x)

sp.integrate(fx, x)

Act 4: Techniques of integration#

Substitution trick#

Example 14#

Integration by parts#

Example 15#

Other techniques#

Computing integrals numerically using SciPy#

We’ll now show some examples using the function quad form the module scipy.integrate.

The function quad(f,a,b) is short for quadrature,

which is an old name for computing areas.

Example 11N using SciPy#

Let’s integrate the function \(f(x) = 3\).

from scipy.integrate import quad

def f(x):

return 3

quad(f, 0, 5)

The function quad returns two numbers as output:

the value of the integral and a precision parameter.

In output of the code,

tells us the value of the integral is \(\int_{0}^5 f(x)\,dx\)

is 15.0 and guarantees the accuracy of this value up to an error of \(1.7\times 10^{-13}\).

Since we’re usually only interested in the value of the integral, we often select the first output of quad so you’ll see the code like quad(...)[0] in all the code examples below.

quad(f, 0, 5)[0]

Example 12N using SciPy#

Define the function \(g(x) = x\).

def g(x):

return x

quad(g, 0, 5)[0]

Example 13N using SciPy#

Lets now compute \(\int_{-1}^4 h(x)\,dx\)

def h(x):

return 4 - x**2

quad(h, -2, 2)[0]

Computing integral functions symbolically using SymPy#

This is known as an indefinite integral since the limits of integration are not defined.

In contrast,

a definite integral computes the area under \(f(x)\) between \(x=a\) and \(x=b\).

Use integrate(f, (x,a,b)) to compute the definite integrals of the form \(A(a,b)=\int_a^b f(x) \, dx\):

import sympy as sp

x, a, b = sp.symbols("x a b")

The symbols function creates SymPy symbolic variables.

Unlike ordinary Python variables that hold a particular value,

SymPy variables act as placeholders that can take on any value.

We can use the symbolic variables to create expressions, just like we do with math variables in pen-and-paper calculations.

Example 11S: Constant function#

\(f(x) = 3\)

fx = 3

fx

We’ll use the SymPy function integrate for computing integrals.

We call this function

by passing in the expression we want to integrate as the first argument.

The second argument is a triple \((x,a,b)\),

which specifies the variable of integration \(x\),

the lower limit of integration \(a\),

and the upper limit of integration \(b\).

sp.integrate(fx, (x,a,b)) # = A_f(a,b)

The answer \(3\cdot (b-a)\) is the general expression for calculating the area under \(f(x)=c\), for between any starting point \(x=a\) and end point \(x=b\). Geometrically, this is just a height-times-width formula for the area of a rectangle.

To compute the specific integral between \(a=0\) and \(b=5\) under \(f(x)=3\),

we use the subs (substitute) method,

passing in a Python dictionary of the values we want to “plug” into the general expression.

sp.integrate(fx, (x,a,b)).subs({a:0, b:5})

The integral function (indefinite integral) \(F_0(b) = \int_0^b f(x) dx\) is obtained as follows.

F0b = sp.integrate(fx, (x,0,b)) # = F_0(b)

F0b

We can obtain the area by using \(A_f(0,5) = F_0(5) - F_0(0)\):

F0b.subs({b:5}) - F0b.subs({b:0})

Example 12S: Linear function#

\(g(x) = mx\)

gx = x

gx

The integral function \(G_0(b) = \int_0^b g(x) dx\) is obtained by leaving the variable upper limit of integrartion.

G0b = sp.integrate(gx, (x,0,b)) # = G_0(b)

G0b

We can obtain the definite intagral using \(\int_0^5 g(x)\,dx = G_0(5) - G_0(0)\):

G0b.subs({b:5}) - G0b.subs({b:0})

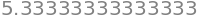

SymPy computed the exact answer for us as a fraction \(\frac{25}{2}\). We can force SymPy to produce a numeric answer by calling \tt{sp.N} on this expression.

sp.N(G0b.subs({b:5}) - G0b.subs({b:0}))

Example 13S: Polynomial function#

\(h(x) = 4 - x^2\)

hx = 4 - x**2

hx

H0b = sp.integrate(hx, (x,0,b))

H0b

We can obtain the area by using \(A_h(0,2) = H_0(2) - H_0(0)\).

H0b.subs({b:2}) - H0b.subs({b:0})

Applications of integration#

Kinematics#

The uniform acceleration motion (UAM) equations…

Let’s analyze the case where the net force on the object is constant. A constant force causes a constant acceleration \(a = \frac{F}{m} = \textrm{constant}\). If the acceleration function is constant over time \(a(t)=a\). We find \(v(t)\) and \(x(t)\) as follows:

t, a, v_i, x_i = sp.symbols('t a v_i x_i')

vt = v_i + sp.integrate(a, (t, 0,t) )

vt

xt = x_i + sp.integrate(vt, (t,0,t))

xt

You may remember these equations from your high school physics class. They are the uniform accelerated motion (UAM) equations:

In high school, you probably had to memorize these equations. Now you know how to derive them yourself starting from first principles.

Solving differential equations#

The fundamental theorem of calculus is important because it tells us how to solve differential equations. If we have to solve for \(f(x)\) in the differential equation \(\frac{d}{dx}f(x) = g(x)\), we can take the integral on both sides of the equation to obtain the answer \(f(x) = \int g(x)\,dx + C\).

A differential equation is an equation that relates some unknown function \(f(x)\) to its derivative.

An example of a differential equation is \(f'(x)=f(x)\).

What is the function \(f(x)\) which is equal to its derivative?

You can either try to guess what \(f(x)\) is or use the dsolve function:

Kinematics revisited#

t, a, k, lam = sp.symbols("t a k \\lambda")

x = sp.Function("x")

newton_eqn = sp.diff(x(t), t, t) - a

sp.dsolve(newton_eqn, x(t)).rhs

Bacterial growth#

b = sp.Function('b')

bio_eqn = k*b(t) - sp.diff(b(t), t)

sp.dsolve(bio_eqn, b(t)).rhs

Radioactive decay#

r = sp.Function('r')

radioactive_eqn = lam*r(t) + sp.diff(r(t), t)

sp.dsolve(radioactive_eqn, r(t)).rhs

Simple harmonic motion (SHM)#

w = sp.symbols("w", nonnegative=True)

SHM_eqn = sp.diff(x(t), t, t) + w**2*x(t)

sp.dsolve(SHM_eqn, x(t)).rhs

Probability calculations#

def fZ(z):

return 1 / np.sqrt(2*np.pi) * exp(-z**2 / 2)

quad(fZ, a=-1, b=1)[0]

quad(fZ, a=-2, b=2)[0]

quad(fZ, a=-3, b=3)[0]

Sequences and series#

Sequences are functions with discrete inputs#

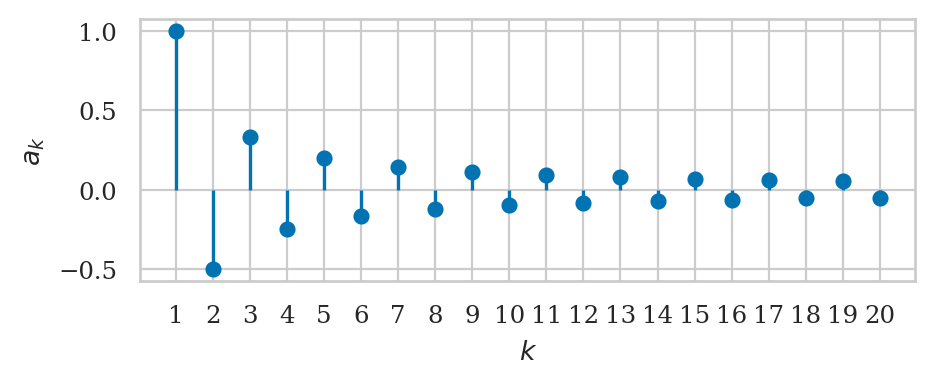

Sequences are functions that take whole numbers as inputs. Instead of continuous inputs \(x\in \mathbb{R}\), sequences take natural numbers \(k\in\mathbb{N}\) as inputs. We denote sequences as \(a_k\) instead of the usual function notation \(a(k)\).

We define a sequence by specifying an expression for its \(k^\mathrm{th}\) term.

The natural numbers#

Squares of natural numbers#

Harmonic sequence#

The alternating harmonic sequence#

Inverse factorial sequence#

Geometric sequence#

Powers of two#

Convergence of sequences#

Divergent sequences#

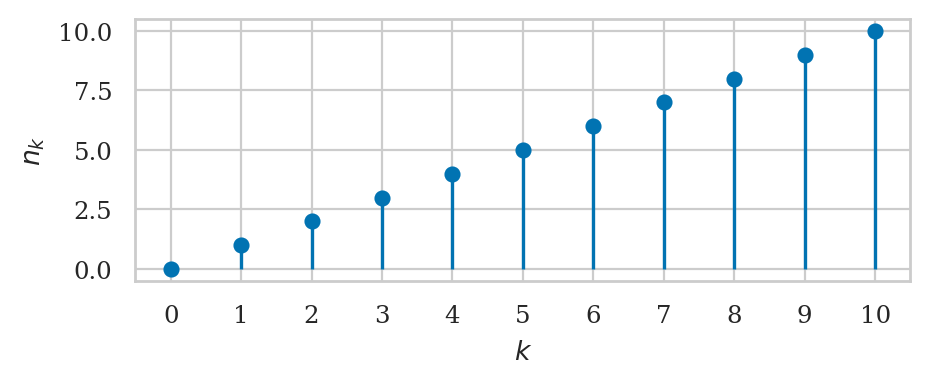

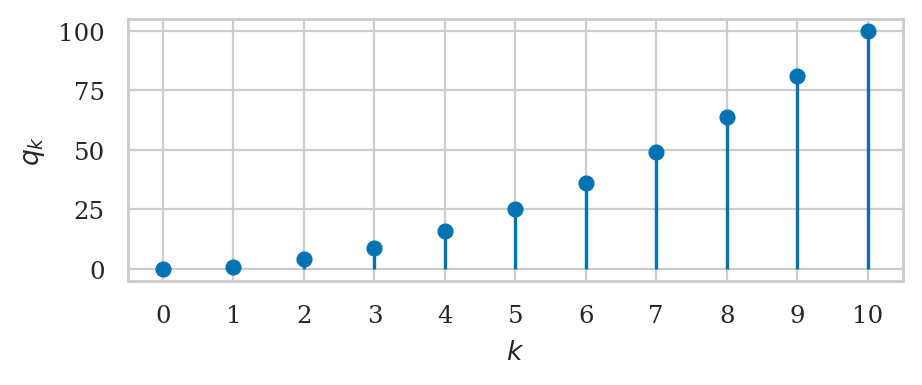

The sequences \(n_k = k\), \(q_k = k^2\), and \(b_k = 2^k \) keep getting larger and larger as \(k\) goes to infinity.

k = sp.symbols("k")

sp.limit(k, k, sp.oo)

sp.limit(k**2, k, sp.oo)

sp.limit(2**k, k, sp.oo)

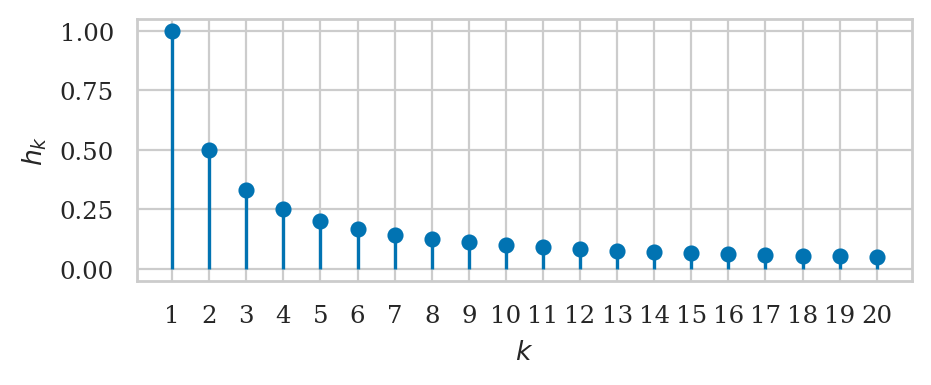

Convergent sequences#

The sequences \(h_k = \tfrac{1}{k}\), \(a_k = \tfrac{(-1)^{k+1}}{k}\), and \(f_k = \tfrac{1}{k!}\) converge to \(0\) in the limit as \(k\) goes to infinity.

sp.limit(1/k, k, sp.oo)

sp.limit_seq((-1)**(k+1)/k, k)

sp.limit(1/sp.factorial(k), k, sp.oo)

Summation notation#

The capital Greek letter sigma stands in for the word sum, and the range of index values included in this sum is denoted below and above the summation sign. For example, the sum of the values in the sequence \(c_k\) from \(k=0\) until \(k=n\) is denoted

Exact formulas for finite summations#

We’ll now show some useful formulas for calculating sum of the terms in certain sequences.

Geometric sums#

The formula for the sum of the first \(n\) terms in the geometric sequence is

Let’s verify this using SymPy.

To work with series,

use the sp.summation function whose syntax is analogous to the sp.integrate function.

r, n = sp.symbols("r n")

sp.summation(r**k, (k,0,n))

We can use this formula to find the sum of the powers of \(2\):

sp.summation(2**k, (k,0,n))

Arithmetic sums#

The sum of the first \(n\) positive integers and the sum of their squares are described by the following formulas:

sp.simplify(sp.summation(k, (k,0,n)))

sp.factor(sp.summation(k**2, (k,0,n)))

Sums of binomial coefficients#

The binomial coefficient is denoted using the symbol \({n \choose k}\), which is read as “\(n\) choose \(k\).” The binomial coefficient counts the number of combinations of \(k\) items we can choose from a set of \(n\) items, and it is computed using the formula: \({n \choose k} = \frac{n!}{(n-k)! \, k!}\). For example, the number of combinations of size \(2\) selected from a list of \(5\) items is \({5 \choose 2} = \frac{5!}{(5-2)!\,2!} = \frac{5!}{3!\,2!} = \frac{5\cdot 4 \cdot 3 \cdot 2 \cdot 1}{3 \cdot 2 \cdot 1 \;\; \cdot \;\; 2 \cdot 1 } = \frac{120}{6 \cdot 2} = 10\).

The binomial coefficient appears in the expansion of the binomial expression \((a + b)^n\), which can written as the following summation:

This sum appears in several calculations in probability theory.

Series#

Series are sums of sequences. Summing the values of a sequence \(a_k:\mathbb{N}\to \mathbb{R}\) is analogous to taking the integral of a function \(f:\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\).

Series are defined as the sums computed from the terms in the sequence \(c_k\). The finite series \(\sum_{k=1}^n c_k\) computes the first \(n\) terms of the sequence:

The infinite series \(\sum c_k\) computes all the terms in the sequence:

The infinite series \(\sum c_k\) of the sequence \(c_k : \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{R}\) is analogous to the integral \(\int_0^\infty f(x) \,dx\) of a function \(f : \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\).

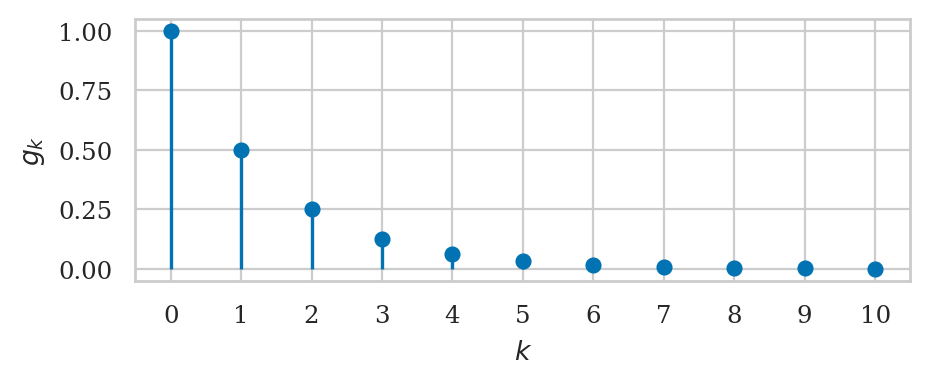

Some infinite series converge to a finite value. For example, when \(|r|<1\), the limit as \(n \to \infty\) of the geometric series converges to the following value:

This expression describes an infinite sum, which is not possible to compute in practice, but we can see the truth of this equation using our mind’s eye. The formula for first \(n\) terms is the geometric series is \(G_n = \frac{1-r^{n+1}}{1-r}\). The term \(r^{n+1}\) goes to zero as \(n \to \infty\), so the only part of the formula that remains is \(\frac{1}{1-r}\).

r = sp.symbols("r")

sp.summation(r**k, (k,0,sp.oo))

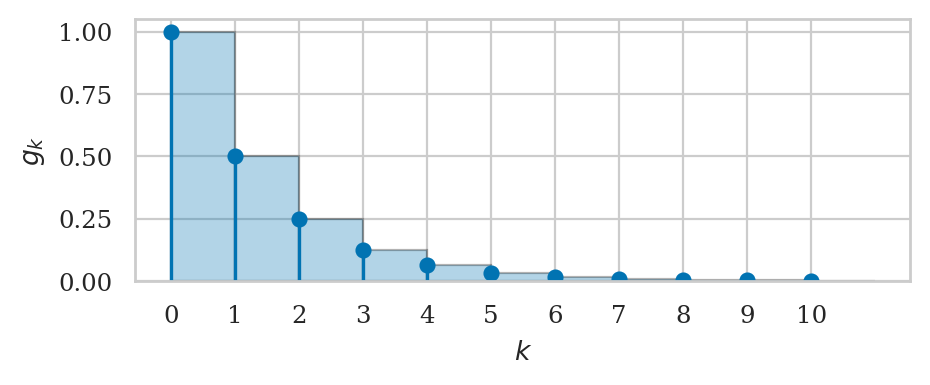

Example 16: sum of a geometric series#

from ministats.calculus import plot_series

def g_k(k):

return (1/2)**k

plot_series(g_k, start=0, stop=10, label="$g_k$");

sum([g_k(k) for k in range(0, 10)])

sum([g_k(k) for k in range(0, 20)])

sum([g_k(k) for k in range(0, 100)])

Confirm the exact sum by computing the limit to infinity using SymPy.

sp.summation((1/2)**k, (k,0,sp.oo))

Convergent and divergent series#

We say the geometric series \(G_\infty = \sum g_k = \sum_{k=0}^\infty r^k\) converges to the value \(\frac{1}{1-r}\). We can also say that the infinite geometric series \(\sum g_k\) is convergent, meaning it has a finite value and doesn’t blow up. Another example of a converging infinite series is \(F_\infty = \sum f_k\), which converges to the number \(e\), as we’ll see in Example 17 below.

In contrast, the harmonic series \(\sum h_k\) diverges. When we sum together more and more terms of the sequences \(h_k\), the total computed keeps growing and the infinite series blows up to infinity \(\sum h_k = \infty\). We say that the harmonic series is divergent.

for n in [20, 100, 1000, 10000, 1_000_000]:

H_n = sum([h_k(k) for k in range(1, n)])

print("Harmonic series up to n=", n, "is", H_n)

Harmonic series up to n= 20 is 3.547739657143682

Harmonic series up to n= 100 is 5.177377517639621

Harmonic series up to n= 1000 is 7.484470860550343

Harmonic series up to n= 10000 is 9.787506036044348

Harmonic series up to n= 1000000 is 14.39272572286499

sp.summation(1/k, (k,1,sp.oo))

Using convergent series for practical calculations#

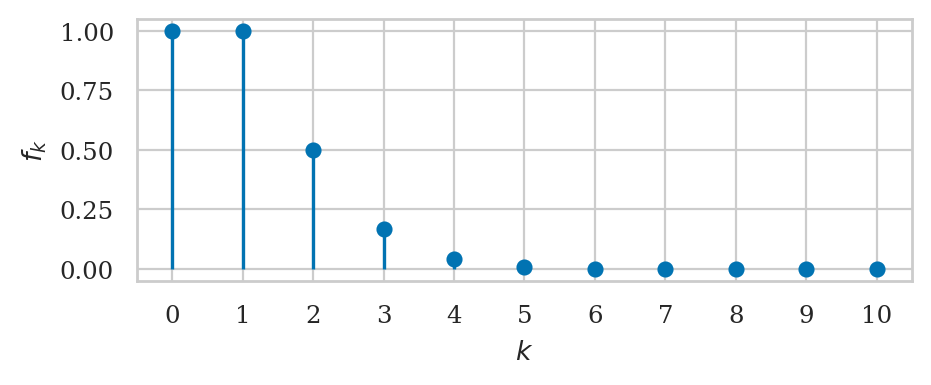

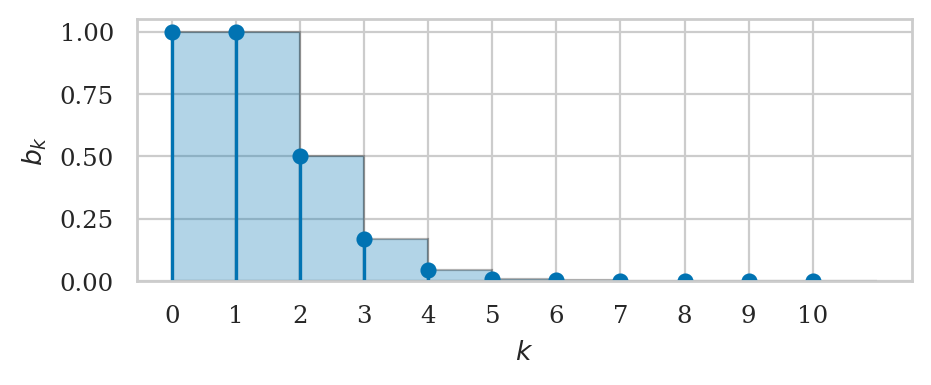

Example 17: Euler’s number#

The infinite sum of the sequence \(f_k = \tfrac{1}{k!}\) converges to Euler’s number \(e = 2.71828182845905\ldots\):

The calculation above is not just cool math fact, but a useful computational procedure that we can use to approximate the value of \(e = 2.71828\ldots\) using only basic arithmetic operations like repeated multiplication (factorial), division, and addition.

Let’s start with a visualization of the series.

import math

def f_k(k):

return 1 / math.factorial(k)

plot_series(f_k, start=0, stop=10, label="$b_k$");

Using a Python for-loop,

we can obtain an approximation to \(e\) that is accurate to six decimals by summing 10 terms in the series:

sum([f_k(k) for k in range(0, 10)])

sum([f_k(k) for k in range(0, 15)])

sum([f_k(k) for k in range(0, 20)])

The approximation we obtain using 20 terms in a series is a very good approximation to the exact value.

import math

math.e

The SymPy function sp.summation to compute the infinite sum.

sp.summation(1/sp.factorial(k), (k,0,sp.oo))

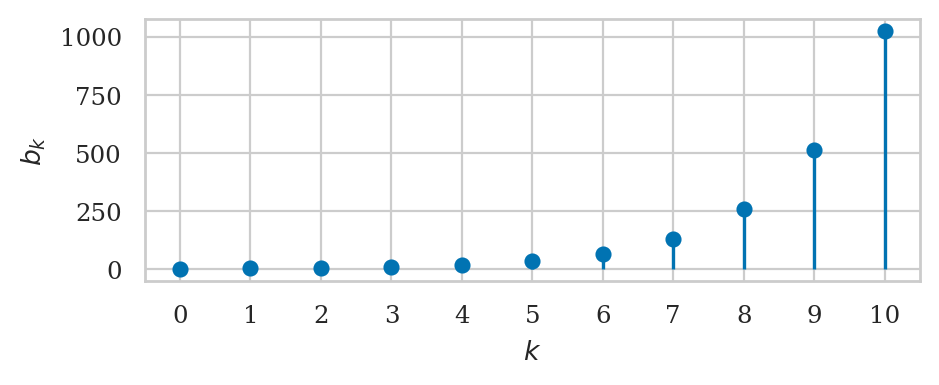

Example 18: Natural logarithm of 2#

def a_k(k):

return (-1)**(k+1) / k

for n in [10, 100, 1000, 1_000_000]:

A_n = sum([a_k(k) for k in range(1,n+1)])

print("Alternating geometric series up to n=", n, "is", A_n)

Alternating geometric series up to n= 10 is 0.6456349206349207

Alternating geometric series up to n= 100 is 0.688172179310195

Alternating geometric series up to n= 1000 is 0.6926474305598223

Alternating geometric series up to n= 1000000 is 0.6931466805602525

math.log(2)

sp.summation((-1)**(k+1) / k, (k,1,sp.oo))

Power series#

The term power series describes a series whose terms contain different powers of the variable \(x\). The \(k\)^th^ term in a power series consists of some coefficient \(c_k\) and the \(k\)^th^ power of \(x\):

The math expression we obtain in this way is a polynomial of degree \(n\) in \(x\), which we denote \(P_n(x)\). Depending on the choice of the coefficients \((c_0, c_1, c_2, c_3, \ldots, c_n)\) we can make the polynomial function \(P_n(x)\) approximate some other function \(f : \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\). To find such approximations, we need some way to choose the coefficients \(c_k\) of the power series, so that the resulting polynomial approximates the function: \(P_n(x) \approx f(x)\).

Taylor series#

The Taylor series approximation to the function \(f(x)\) is a power series whose coefficients \(c_k\) are computed by evaluating the \(k\)th derivative of the function \(f(x)\) at \(x=0\), which we denote \(f^{(k)}(0)\). Specifically, the \(k\)^th^ coefficient in the Taylor series approximation for the function \(f(x)\) is \(c_k = \frac{f^{(k)}(0)}{k!}\), where \(k!\) is the factorial function.

The finite series with \(n\) terms produces the following approximation:

In the limit as \(n\) goes to infinity, the Taylor series approximation becomes exactly equal to the function \(f(x)\):

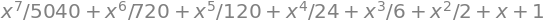

Using this formula and your knowledge of derivative formulas, you can compute the Taylor series of any function \(f(x)\). For example, let’s find the Taylor series of the function \(f(x) = e^x\) at \(x=0\). The first derivative of \(f(x) = e^x\) is \(f^{\prime\!}(x) = e^x\). The second derivative of \(f(x) = e^x\) is \(f^{\prime\prime\!}(x) = e^x\). In fact, all the derivatives of \(f(x)\) will be \(e^x\) because the derivative of \(e^x\) is equal to \(e^x\). The \(k\)th coefficient in the power series of \(f(x)=e^x\) at the point \(x=0\) is equal to the value of the \(k\)th derivative of \(f(x)\) evaluated at \(x=0\) divided by \(k!\). In the case of \(f(x) = e^x\), we have \(f^{(k)}(0) = e^0 = 1\), so the coefficient of the \(k\)th term is \(c_k = \tfrac{f^{(k)}(0)}{k!} = \tfrac{1}{k!}\).

The Taylor series of \(f(x) = e^x\) is

Taylor series are a powerful computational tool for approximating functions. As we compute more terms from the above series, the polynomial approximation to the function \(f(x)=e^x\) becomes more accurate.

x = sp.symbols("x")

# first derivative of e^x at x=0

sp.diff(sp.exp(x), x, 1).subs({x:0})

# second derivative of e^x at x=0

sp.diff(sp.exp(x), x, 2).subs({x:0})

# fifth derivative of e^x at x=0

sp.diff(sp.exp(x), x, 5).subs({x:0})

exp_c_k = x**k / sp.factorial(k)

sp.Sum(exp_c_k, (k,0,7))

sp.Sum(exp_c_k, (k,0,7)).doit()

sp.summation( exp_c_k.subs({x:0}), (k,0,sp.oo))

This is the value \(\exp(0) = e^0 = 1\).

We can also compute \(e^5\):

sp.summation( exp_c_k.subs({x:5}), (k,0,sp.oo))

Obtaining Taylor series using SymPy#

The SymPy function series is a convenient way to obtain the series of any function fun.

Calling sp.series(fun,var,x0,n)

will show you the series expansion of expr

near var=x0 including all powers of var less than n.

import sympy as sp

x = sp.symbols("x")

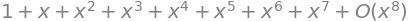

sp.series(1/(1-x), x, x0=0, n=8)

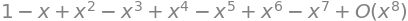

sp.series(1/(1+x), x, x0=0, n=8)

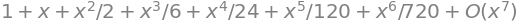

sp.series(sp.E**x, x, x0=0, n=7)

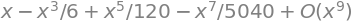

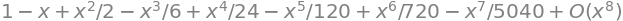

sp.series(sp.sin(x), x, x0=0, n=9)

sp.series(sp.cos(x), x, x0=0, n=8)

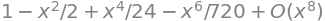

sp.series(sp.ln(x+1), x, x0=0, n=6)

Applications of series#

Series allow us to compute numbers like \(e\), \(\pi\), \(\ln(2)\), etc. Taylor series allow us to approximate functions.

The Taylor series representation for the function \(f(x)\) also provides an easy way to compute its integral function \(F_0(x) = \int_0^x f(u)\,du\). The Taylor series of \(f(x)\) consists only of polynomial terms of the form \(c_n x^n\). To compute the integral function \(F_0(x) = \int_0^x f(u)\,du\), we can compute the integrals of the individual terms, which gives us \(\frac{c_n}{n+1}x^{n+1}\).

Multivariable calculus#

In multivariable calculus, we extend the ideas of differential and integral calculus to functions with multiple input variables.

Multivariable functions#

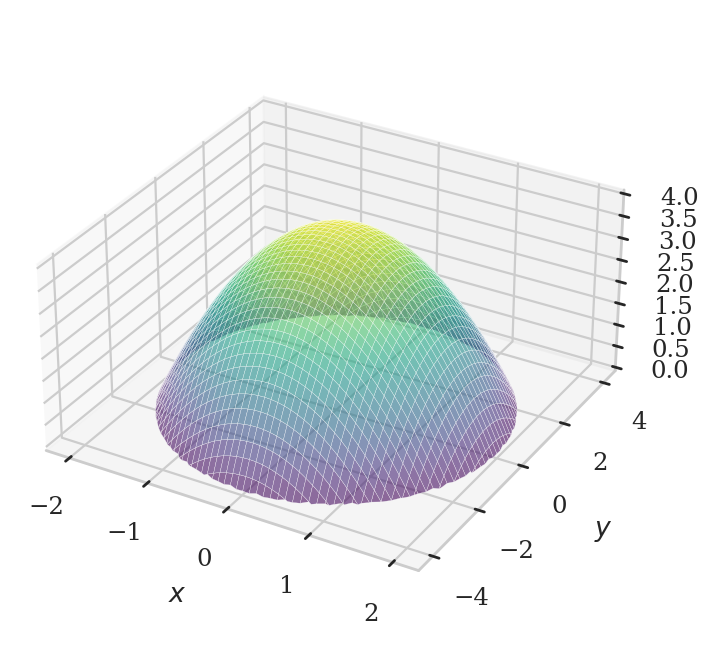

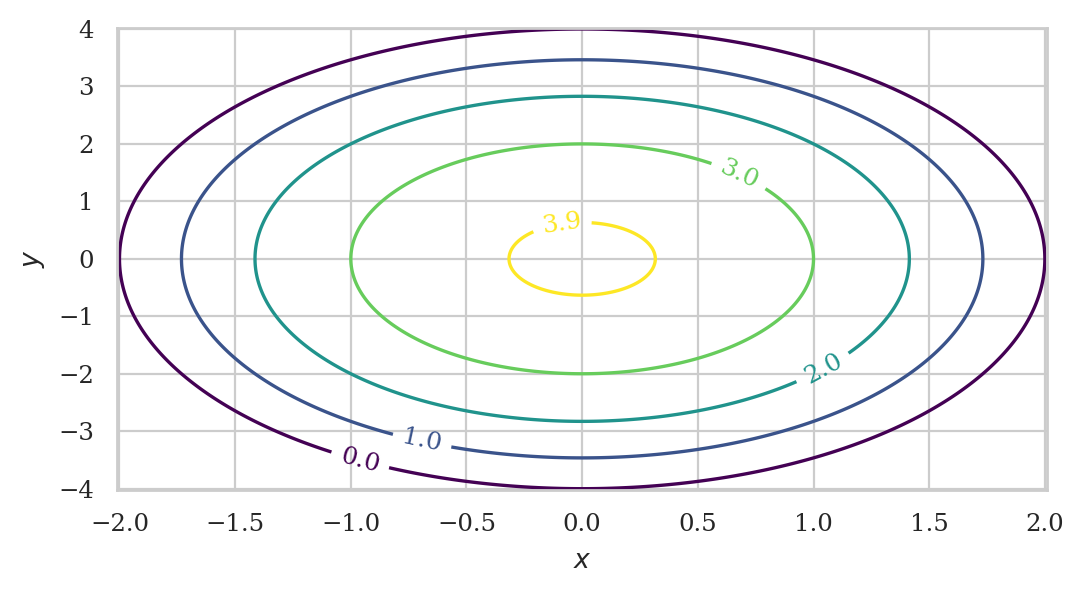

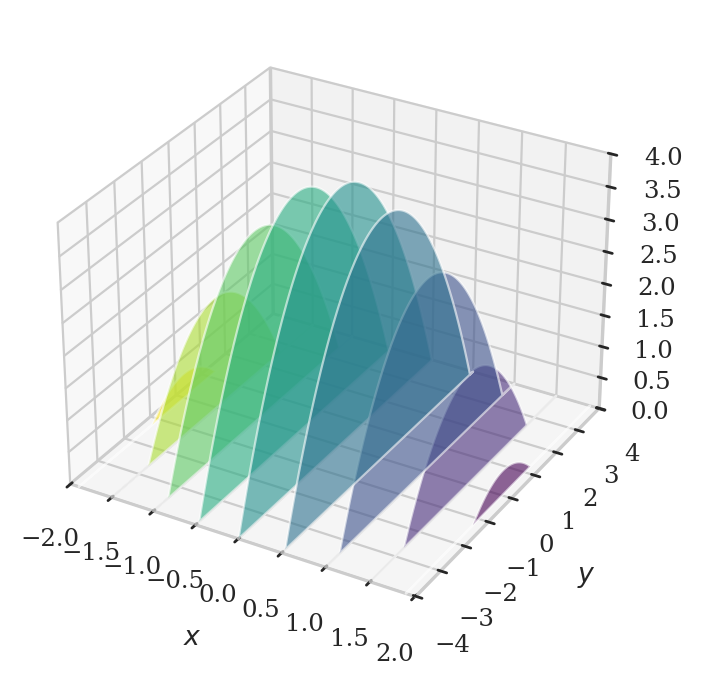

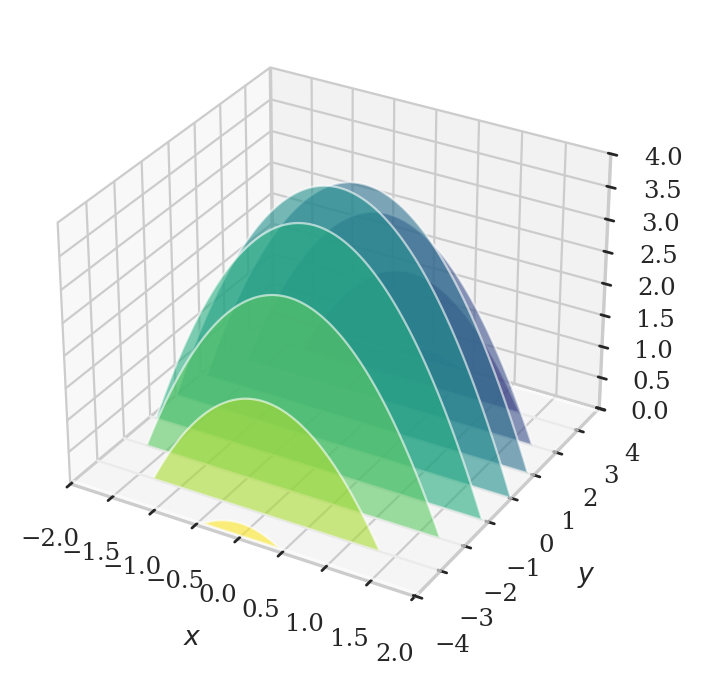

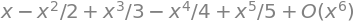

Consider the bivariate function \(f(x,y) = 4 - x^2 - \frac{1}{4}y^2\).

x, y = sp.symbols("x y")

fxy = 4 - x**2 - y**2/4

fxy

We can plot this function as a surface in a three-dimensional space.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

xmax = 2.01

ymax = 4.02

xs = np.linspace(-xmax, xmax, 300)

ys = np.linspace(-ymax, ymax, 300)

X, Y = np.meshgrid(xs, ys)

Z = 4 - X**2 - Y**2/4

# Surface plot

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(4,4))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection="3d")

Zpos = np.ma.masked_where(Z < 0, Z)

surf = ax.plot_surface(X, Y, Zpos,

# rstride=3, cstride=3,

alpha=0.6,

linewidth=0.1,

antialiased=True,

cmap="viridis")

ax.set_box_aspect((2, 2, 1))

ax.set_xlabel("$x$")

ax.set_ylabel("$y$")

ax.set_zlabel("$f(x,y)$");

We can trace level curves in the surface, to produce a “topographic map” of the surface where each level curve shows the points that are at a certain height.

Partial derivatives#

sp.diff(fxy, x)

sp.diff(fxy, y)

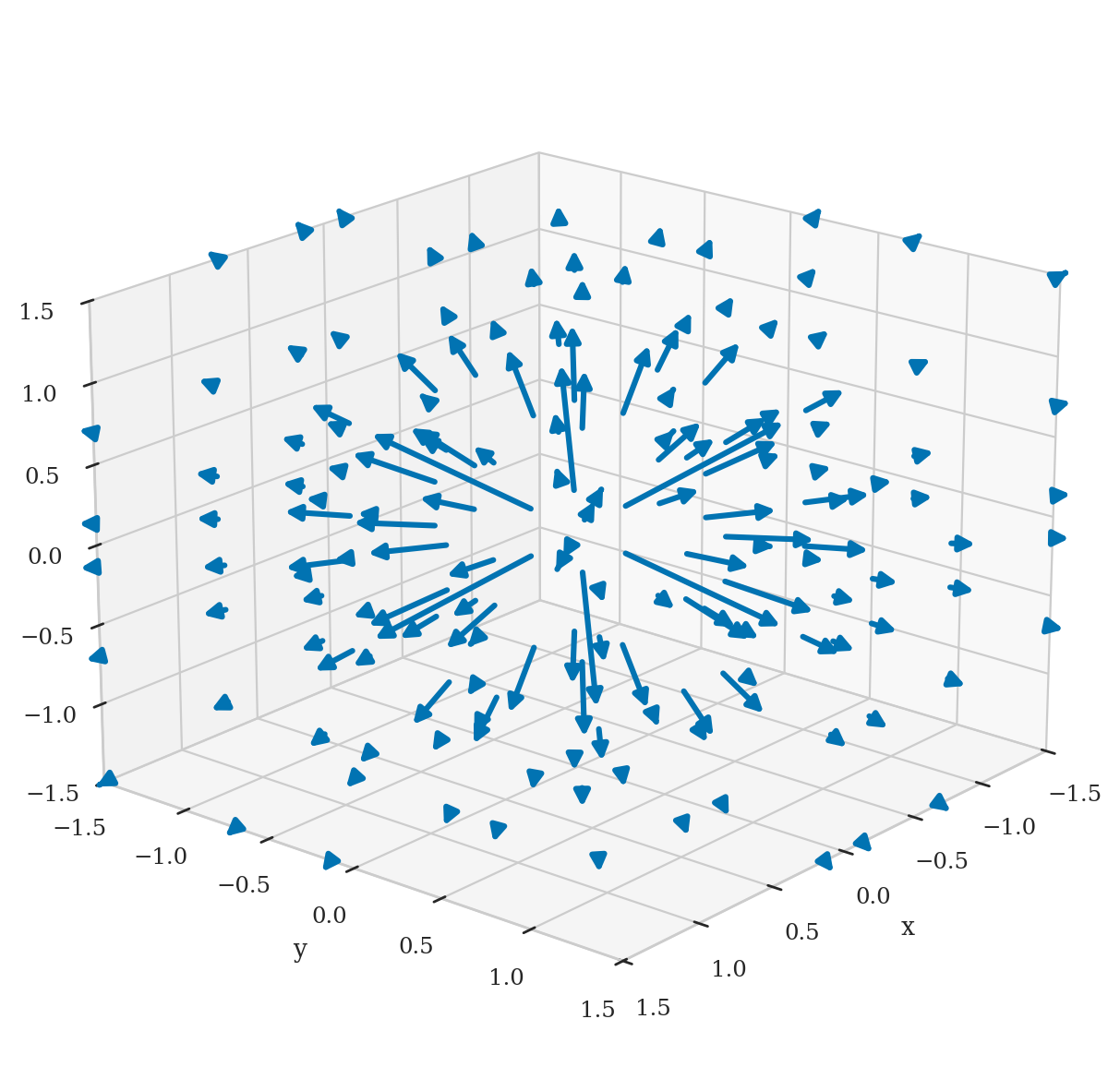

The gradient operator#

[sp.diff(fxy, x), sp.diff(fxy, y)]

Partial integration#

from ministats.book.figures import plot_slices_through_paraboloid

plot_slices_through_paraboloid(direction="x");

Double integrals#

The multivariable generalization of the integral \(\int_a^b f(x) \, dx\) that computes the total amount of \(f(x)\) between \(a\) and \(b\) is the multivariable integral of the form:

where \(R\) is called the \emph{region of integration} and corresponds to some subset of the Cartesian plane \(\mathbb{R} \times \mathbb{R}\).

Applications of multivariable calculus#

Multivariable functions appear all the time in machine learning, engineering, physics, and other sciences. The optimization techniques we learned for single variables generalize to functions with multiple variables. Indeed, the gradient descent algorithm is often used to optimize functions with hundreds or thousands of variables. Multivariable integrals are used a lot in probability theory and statistics, where they are used to compute probabilities and expectations. Your basic knowledge of derivatives and integrals concepts we discussed earlier in this tutorial will be very useful for understanding multivariable calculus topics.

Vector calculus#

Example: electric field around a positive charge#

The strength of the electric field \(\mathbf{E}\) at the point \(\mathbf{r} = (x,y,z)\) is

where \(k\) is Coulomb’s constant, \(r = |\mathbf{r}| = \sqrt{x^2+y^2+z^2}\) is the distance from the origin, and \(\hat{\mathbf{r}} = \frac{\mathbf{r}}{r}\) is a unit vector in the same direction as \(\mathbf{r}\).

Vector calculus derivatives#

The derivative operator \(\nabla\) (nabla) is defined as \(\nabla = \big( \frac{\partial}{\partial x}, \frac{\partial}{\partial y}, \frac{\partial}{\partial z} \big)\).

The divergence of the vector field \(\mathbf{F}\) is computed by taking the “dot product” of \(\nabla\) and the vector field \(\mathbf{F} = (F_x, F_y, F_z)\):

The divergence tells us if the field \(\mathbf{F}\) is acting as a “source” or a “sink” at the point \((x,y,z)\).

The curl of the vector field \(\mathbf{F}\) is defined as the “cross product” of \(\nabla\) and the vector field \(\mathbf{F} = (F_x, F_y, F_z)\):

The curl tells us the rotational tendency of the vector field \(\mathbf{F}\).

Vector calculus integrals#

Path integrals#

The concept of a vector path integral is denoted \(\int_C \mathbf{F}(\mathbf{r}) \cdot d\mathbf{r}\), where \(C\) is some curve in three dimensional space, and \(d\mathbf{r}\) describes a short step along this curve. This integral computes the total action of the vector field \(\mathbf{F}\) in the direction along the curve \(C\).

Surface integrals#

The vector surface integral is denoted \(\iint_S \mathbf{F}(\mathbf{r}) \cdot d\mathbf{S}\), where \(S\) is some surface in three dimensional space, and \(d\mathbf{S}\) is a small “piece of the surface.” This integral computes the total flux of the vector field \(\mathbf{F}\) flowing through the surface \(S\).

Applications of vector calculus#

Vector calculus is used in physics (electricity and magnetism, mechanics, thermodynamics) and electrical engineering.

Practice problems#

Learning calculus requires calculating lots of limits, derivatives, and integrals. Here are some practice problems for you.

P1 Calculate the following limit expressions:

x = sp.symbols("x")

# (a)

sp.limit(7/(x+4), x, sp.oo)

# (b)

sp.limit((4*x**2-7*x+1)/ x**2, x, sp.oo)

# (c)

sp.limit(1/x, x, 0, "-")

P2 Assuming \(\displaystyle\lim_{x\to\infty} f(x)= 2\) and \(\displaystyle\lim_{x\to\infty} g(x)=3\), compute: $\(\text{(a)}~\!\!\lim_{x\to\infty}\bigl(2f(x)-g(x)\bigr) \quad \text{(b)}~\!\!\lim_{x\to\infty} f(x)g(x) \quad \text{(c)}~\!\!\lim_{x\to\infty}\tfrac{4f(x)}{g(x)+1}.\)$

P3 Find the derivative with respect to \(x\) of the functions: $\(\text{(a)}~f(x) = x^{13} \qquad \text{(b)}~g(x) = \sqrt[3]{x} \qquad \text{(c)}~h(x) = ax^2 + bx + c.\)$

# (a)

sp.diff(x**13)

# (b)

sp.diff(sp.root(x,3), x)

# (c)

a, b, c = sp.symbols("a b c")

sp.diff(a*x**2 + b*x + c, x)

P4 Calculate the derivatives of the following functions: $\(\text{(a)}~p(x) = \tfrac{2x + 3}{3x + 2} \qquad \text{(b)}~q(x) = \sqrt{x^2 + 1} \qquad \text{(c)}~r(\theta) = \sin^3 \theta.\)$

# (a)

sp.together(sp.diff((2*x+3)/(3*x+2), x))

# (b)

sp.diff(sp.sqrt(x**2+1), x)

# (c)

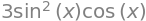

sp.diff((sp.sin(x))**3, x)

P5 Find the maximum and the minimum of \(f(x) = x^5-5x\).

x = sp.symbols("x", real=True)

fx = x**5 - 5*x

dfdx = sp.diff(fx, x)

sols = sp.solve(dfdx, x)

sols

df2dx2 = sp.diff(fx, x, x)

print("When x =", sols[0], ", f''(-1) =", df2dx2.subs({x:sols[0]}), "so maximum")

When x = -1 , f''(-1) = -20 so maximum

print("When x =", sols[1], ", f''(1) =", df2dx2.subs({x:sols[1]}), "so minimum")

When x = 1 , f''(1) = 20 so minimum

P6 Calculate the integral function \(F_0(b) = \int_0^b f(x)\,dx\) for the polynomial \(f(x) = 4x^3 + 3x^2 + 2x + 1\).

F0b = sp.integrate(4*x**3 + 3*x**2 + 2*x + 1, (x,0,b))

F0b

P7 Find the area under \(f(x)=8-x^3\) from \(x=0\) to \(x=2\).

def fcubic(x):

return 8 - x**3

quad(fcubic, a=0, b=2)[0]

P8 Find the area under the graph of the function \(g(x)=\sin(x)\) between \(x=0\) to \(x=\pi\).

quad(np.sin, a=0, b=np.pi)[0]

P9 Compute \(\int_{0}^{1} \frac{4x}{(1+x^2)^3}\,dx\) using the

substitution \(u = 1 + x^2\). Check your answer numerically using the

SciPy function quad.

sp.integrate(4*x/(1+x**2)**3, (x,0,1))

P10 Calculate the value of the infinite series \(\sum_{k=0}^\infty \left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^{\!k}\).

sp.summation((2/3)**k, (k,0,sp.oo))

P11 Find the Taylor series for the function \(f(x) = e^{-x}\).

sp.series(sp.exp(-x), x, 0, 8)

Bonus question#

Compute the definite integral \(\int_{-\infty}^\infty e^{-x^2}\,dx\)

numerically using the quad function.

def expxsq(x):

return np.exp(-x**2)

quad(expxsq, a=-np.inf, b=np.inf)[0]

Links#

Here are some recommended resources to learn more about calculus.

[ Calculus for beginners and srtists ]

https://math.mit.edu/~djk/calculus_beginners/

via https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=41086531

[ Jim Fowler video lectures ]

https://www.youtube.com/@kisonecat/playlists

[ Highlights of Calculus lectures by Gilbert Strang ]

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLBE9407EA64E2C318

[ Nice visualization of integration ]

https://x.com/abakcus/status/1898933342457758033

Book plug#

This material in this tutorial comes from …