Appendix D — Pandas tutorial#

The Python library Pandas is a versatile toolbox for working with tabular data. Pandas is often used for data loading from different sources, data cleaning, data transformations, statistical analysis, and many other data management tasks. This tutorial will introduce you to the central Pandas functionality with a specific focus on the data manipulation tasks used in statistics.

Click the binder button

or this link

bit.ly/46gBen4

to play with the tutorial notebook interactively.

Pandas overview#

The Pandas library provide many helper functions for data management tasks and statistical calculations. Pandas functionality is organized around data frame objects, which are containers objects for tabular data. A Pandas data frame is roughly equivalent to a spreadsheet that contains data values organized into rows and columns. Similar to spreadsheet software, a Pandas data frame provides functions for computing sums, averages, sorting, filtering values, etc.

The goal of this tutorial is to reach you to use Pandas for practical data management tasks. Becoming good at data management will give you the practical skills you need to apply statistics in real-world scenarios. Indeed, professional statisticians and data scientists spend a large proportion of their time on data extraction, data processing, and data cleaning tasks, which are essential prerequisites consist of the significant part of the work for any statistical analysis. Pandas is like a Swiss Army knife of data manipulations, which makes it very useful for all these data manipulation tasks.

Learning objectives#

In this tutorial, I’m going to show you how to …

TODO import from gdoc

Notebook setup#

Before we begin the tutorial, we we must take care of some preliminary tasks to prepare the notebook environment. Feel free to skip this commands

Installing Pandas and other libraries#

We can install Python package pandas in the current environment using the %pip Jupyter magic command.

%pip install --quiet pandas

[notice] A new release of pip is available: 26.0 -> 26.0.1

[notice] To update, run: pip install --upgrade pip

Note: you may need to restart the kernel to use updated packages.

We’ll use the same command to install some additional Python packages that we’ll need throughout the tutorial.

%pip install --quiet ministats lxml odfpy openpyxl xlrd sqlalchemy

[notice] A new release of pip is available: 26.0 -> 26.0.1

[notice] To update, run: pip install --upgrade pip

Note: you may need to restart the kernel to use updated packages.

The ministats package provides a helper function we’ll use to download datasets.

The lxml, odfpy, openpyxl, and sqlalchemy provide additional functionality

for loading data stored in various file formats.

Setting display options#

Next, we run some commands to configure the display of figures and number formatting.

# high-resolution figures

%matplotlib inline

%config InlineBackend.figure_format = 'retina'

# simplified int and float __repr__

import numpy as np

np.set_printoptions(legacy='1.25')

Download datasets#

We use a helper function from the ministats library

to make sure the datasets/ folder that accompanies this tutorial is present.

# download datasets/ directory if necessary

from ministats import ensure_datasets

ensure_datasets()

datasets/ directory already exists.

With all these preliminaries in place, we can now get the Pandas show started!

Data frames#

Most of Pandas functionality is organized around the data frame objects (DataFrame),

which are containers for tabular data.

A Pandas data frame is analogous to a spreadsheet:

it provides functionality for storing, viewing, and transforming data

organized into rows and columns.

If you understand how DataFrame objects work,

then you’ll know most of what you need to know about data management with Pandas,

so this is why we start the tutorial here.

Creating a data frame from a CSV file#

The most common way to create a data frame object

is to read data from a CSV (Comma-Separated-Values) file.

Let’s look at the raw contents of the sample data file datasets/minimal.csv.

!cat "datasets/minimal.csv"

x,y,team,level

1.0,2.0,a,3

1.5,1.0,a,2

2.0,1.5,a,1

2.5,2.0,b,3

3.0,1.5,b,3

The first line in the CSV file is called the header row

and contains the variables names: x, y, team, and level,

separated by commas.

The next five rows contain the data values separated by commas.

The data corresponds to five players in a computer game.

The columns x and y describe the position of the player,

the variable team indicates which team the player is part of,

and the column level specifies the character’s strength.

We want to load the data file datasets/minimal.csv into Pandas.

We start by importing the pandas library under the alias pd

then call the Pandas function pd.read_csv(),

which is used load data from CSV files.

import pandas as pd

df = pd.read_csv("datasets/minimal.csv")

df

| x | y | team | level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | a | 3 |

| 1 | 1.5 | 1.0 | a | 2 |

| 2 | 2.0 | 1.5 | a | 1 |

| 3 | 2.5 | 2.0 | b | 3 |

| 4 | 3.0 | 1.5 | b | 3 |

The import statement makes all the Pandas functions available under the alias pd,

which is the standard short-name used for Pandas in the data science community.

On the next line,

the function pd.read_csv() reads the contents of the data file datasets/minimal.csv

and stores them into a data frame called df,

which we then display on the final line.

The data frame df is fairly small,

so it makes sense to display it in full.

When working with larger data frames with thousands or millions of rows,

it will not be practical to print all their contents.

We can use the data frame method .head(k)

to prints the first k rows the data frame

to see what the data looks like.

df.head(2)

| x | y | team | level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | a | 3 |

| 1 | 1.5 | 1.0 | a | 2 |

We can also use df.tail(k) to print the last \(k\) rows of the data frame,

or df.sample(k) to select k rows at random from the data frame.

Data frame properties#

We’ll use the data frame df for many of the examples in the remainder of this tutorial,

which is why we gave it a very short name.

Let’s explore the attributes and methods of the data frame df.

First let’s use the Python function type to confirm that df is indeed a data frame object.

type(df)

pandas.core.frame.DataFrame

The above message tells us that the df object

is an instance of the DataFrame class.

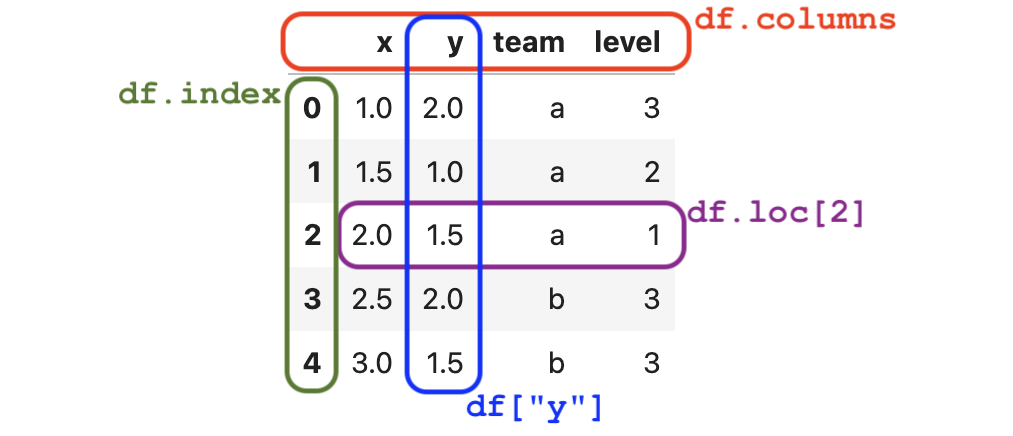

Every data frame has the attributes index and columns,

as illustrated in the following figure:

Figure 1. The anatomy is the data frame

Figure 1. The anatomy is the data frame df with annotations for its different parts.

Rows index#

The index of the data frame contains unique labels

that we use to refer to the rows of the data frame.

The row-index labels in data frames

are analogous to the row numbers used in spreadsheets.

df.index

RangeIndex(start=0, stop=5, step=1)

list(df.index)

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4]

The data frame df uses the “default” range index

that consists of a sequence integer labels: [0,1,2,3,4].

More generally,

index values can be arbitrary labels:

text identifiers, dates, timestamps, etc.

Columns index#

The columns-index attribute .columns tells us the names of the columns (variables) in the data frame.

df.columns

Index(['x', 'y', 'team', 'level'], dtype='object')

These column names were automatically determined based on header row in the CSV file.

Column names usually consist of short textual identifiers for the variable (Python strings).

Spaces and special characters are allowed in column names,

so we could have used names like "x position" and "level (1 to 3)" if we wanted to.

However,

long column names make data manipulation code more difficult to read,

so they are discouraged.

Shape, data types, and momory usage#

Another important property of the data frame is its shape.

df.shape

(5, 4)

The shape of the data frame df is \(5 \times 4\),

which means it has five rows and four columns.

The .dtypes (data types) attribute

tells us what type of data is stored in each of the columns.

df.dtypes

x float64

y float64

team object

level int64

dtype: object

We see that the columns x and y contain floating point numbers,

the column team can contain arbitrary Python objects (in this case Python strings),

and the column level contains integers.

The method .info() provides additional information about the data frame object df,

including missing values (null values) and the total memory usage.

df.info(memory_usage="deep")

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 5 entries, 0 to 4

Data columns (total 4 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 x 5 non-null float64

1 y 5 non-null float64

2 team 5 non-null object

3 level 5 non-null int64

dtypes: float64(2), int64(1), object(1)

memory usage: 538.0 bytes

The data frame df takes up 502 bytes of memory, which is not a lot.

You don’t have to worry about memory usage for any of the datasets we’ll analyze in this book,

since they are all small- and medium-sized.

Accessing and selecting values#

We use the .loc[] attribute to access rows, columns, and individual values within data frames.

Accessing individual values#

We use the syntax df.loc[<row>,<col>]

to select the value with row label <row>

and column label <col> in the data frame df.

For example,

to extract the value of the variable y

for the third row, we use:

df.loc[2,"y"]

1.5

Note the row label 2

is a particular value within the rows-index df.index

and not the sequential row number:

the row label just happens to be same as the row number in this case.

Selecting entire rows#

To select rows from a data frame,

we use df.loc[<row>,:],

where <row> is the rows-index label

and : is shorthand for “all columns.”

row2 = df.loc[2,:]

row2

x 2.0

y 1.5

team a

level 1

Name: 2, dtype: object

The rows of a data frame are Pandas Series objects,

which are one-dimensional containers for data values.

type(row2)

pandas.core.series.Series

We’ll defer the discussion on Series objects until the next section.

For now,

I just want you to know that series have an index property,

which tells you the labels you must use to access the values in the series.

The index of the series row2 is the same as the columns index of the data frame.

row2.index

Index(['x', 'y', 'team', 'level'], dtype='object')

We can access individual elements using these index labels.

row2["y"]

1.5

If you need iterate through all the rows of the data frame,

you can use the df.iterrows() method as part of a for-loop.

For example, for idx, row in df.iterrows().

Selecting entire columns#

We use the syntax df[<col>] to select the column <col> from a data frame.

For example,

here is how to select the column y from the data frame df.

ys = df["y"]

ys

0 2.0

1 1.0

2 1.5

3 2.0

4 1.5

Name: y, dtype: float64

The column ys is a Pandas series

and its index is the same as the data frame index df.index = [0,1,2,3,4].

ys.index

RangeIndex(start=0, stop=5, step=1)

We can select individual values within the series ys

using the index labels.

ys[2]

1.5

The column-selector syntax df[<col>]

is shorthand for the expression df.loc[:,<col>],

which means “select all the rows for the column <col>.”

We can verify that df["y"] equals df.loc[:,"y"] using the .equals() method.

df["y"].equals( df.loc[:,"y"] )

True

If you need iterate through all the columns of the data frame,

you can use the df.items() method in a for-loop.

For example, for name, col in df.items().

Selecting multiple columns#

We can extract multiple columns from a data frame by passing a list of column names inside the square brackets.

df[["x", "y"]]

| x | y | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.0 | 2.0 |

| 1 | 1.5 | 1.0 |

| 2 | 2.0 | 1.5 |

| 3 | 2.5 | 2.0 |

| 4 | 3.0 | 1.5 |

The result is a new data frame object

that contains only the x and y columns from the original df.

Selecting only certain rows#

A common task when working with data frames is to select the rows that fit one or more criteria. We usually carry out this selection procedure in two steps:

Build a boolean “selection mask” that contains the value

Truefor the rows we want to keep, and the valueFalsefor the rows we want to filter out.Select the subset of rows from the data frame using the mask. The result is a new data frame that contains only the rows that correspond to the

Truevalues in the selection mask.

For example,

to select the rows from the data frame that are part of team b,

we first build the selection mask.

mask = df["team"] == "b"

mask

0 False

1 False

2 False

3 True

4 True

Name: team, dtype: bool

The rows that match the criterion “team column equal to b”

correspond to the True values in the mask,

while the remaining values are False.

We can now select the desired subset by placing the mask inside the square brackets.

df[mask]

| x | y | team | level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 2.5 | 2.0 | b | 3 |

| 4 | 3.0 | 1.5 | b | 3 |

The result is a new data frame that contains only the rows that correspond to the True values in the mask series.

We often combine the two steps we described above

into a single expression df[df["team"]=="b"].

This combined expression is a little hard to read at first,

since it contains two pairs of square brackets and two occurrences of the data frame name df,

but you’ll get used to it,

since you’ll see selection expressions many times.

df[df["team"]=="b"]

| x | y | team | level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 2.5 | 2.0 | b | 3 |

| 4 | 3.0 | 1.5 | b | 3 |

We can use the Python bitwise boolean operators & (AND), | (OR) and ~ (NOT)

to build selection masks with multiple criteria.

For example,

to select the rows with team is b where the x value is greater or equal to 3,

we would use the following expression.

df[(df["team"] == "b") & (df["x"] >= 3)]

| x | y | team | level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 3.0 | 1.5 | b | 3 |

The selection mask consists of two terms (df["team"]=="b") and (df["x"]>=3)

that are combined with the bitwise AND operator &.

Note the use of extra parentheses to ensure the masks for the two conditions are computed first before the & operation is applied.

If we want to select multiple values of a variable,

we can use the .isin() method and specify a list of values to compare with.

For example,

to build a mask that select all the observations that have level equal to 2 or 3,

we can use the following code.

df["level"].isin([2,3])

0 True

1 True

2 False

3 True

4 True

Name: level, dtype: bool

We see the above mask correctly selects all observations except the one at index 2,

which has level equal to 1.

Creating data frames from Python objects#

We sometimes obtain data in the form of regular Python objects like lists and dictionaries.

If we want to use Pandas functionality to work with this data,

we’ll need to “package” it as a pd.DataFrame object first.

One way to create a data frame object

is to load a Python dictionary whose keys are the column names,

and whose values are lists of the data in each column.

The code below shows how to create a data frame df2

by initializing a pd.DataFrame object from a columns dictionary.

dict_of_columns = {

"x": [1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5, 3.0],

"y": [2.0, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 1.5],

"team": ["a", "a", "a", "b", "b"],

"level": [3, 2, 1, 3, 3],

}

df2 = pd.DataFrame(dict_of_columns)

df2

| x | y | team | level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | a | 3 |

| 1 | 1.5 | 1.0 | a | 2 |

| 2 | 2.0 | 1.5 | a | 1 |

| 3 | 2.5 | 2.0 | b | 3 |

| 4 | 3.0 | 1.5 | b | 3 |

The data frame df2

is identical to the data frame df that we loaded from the CSV file earlier.

We can confirm this by calling the .equals() method.

df2.equals(df)

True

We can also create a data frame from a list of observation records. Each record (row) corresponds to the data of one observation.

list_of_records = [

[1.0, 2.0, "a", 3],

[1.5, 1.0, "a", 2],

[2.0, 1.5, "a", 1],

[2.5, 2.0, "b", 3],

[3.0, 1.5, "b", 3],

]

columns = ["x", "y", "team", "level"]

df3 = pd.DataFrame(list_of_records, columns=columns)

When using the list-of-records approach,

Pandas can’t determine the names of the columns automatically,

so we pass in the list of column names as the columns argument.

The data frame df3 created from the lists of records

is identical to the data frame df that saw earlier.

df3.equals(df)

True

A third way to create a data frame is to pass in a list of dictionary objects.

list_of_dicts = [

dict(x=1.0, y=2.0, team="a", level=3),

dict(x=1.5, y=1.0, team="a", level=2),

dict(x=2.0, y=1.5, team="a", level=1),

dict(x=2.5, y=2.0, team="b", level=3),

dict(x=3.0, y=1.5, team="b", level=3),

]

df4 = pd.DataFrame(list_of_dicts)

Once again,

the data frame df4 we obtain in this way

is identical to the original df.

df4.equals(df)

True

Data frames exercises#

I invite you to try solving the following exercises before continuing with the rest of the tutorial.

Exercise 1: Select a column#

Select the column that contains the variable x from the data frame df.

# Instructions: write your Pandas code in this cell

Exercise 2: Select rows#

Select the rows from the data frame df that correspond to the players on team a.

# Instructions: write your Pandas code in this cell

Series#

Pandas Series objects are list-like containers of values.

The rows and the and the columns of a data frame are series objects.

Let’s extract the column y from the data frame df

and use it to illustrate the properties of methods of series objects.

ys = df["y"]

ys

0 2.0

1 1.0

2 1.5

3 2.0

4 1.5

Name: y, dtype: float64

The numbers printed on the left are the series index.

The numbers printed on the right are the values in the series.

The last line shows the series name and the data type of the values.

We can call the .info() method on the series ys

to display detailed information about it.

ys.info()

<class 'pandas.core.series.Series'>

RangeIndex: 5 entries, 0 to 4

Series name: y

Non-Null Count Dtype

-------------- -----

5 non-null float64

dtypes: float64(1)

memory usage: 168.0 bytes

Series properties#

The series index tells us the labels we must use to access the values in the series.

The series ys has the same index as the data frame df.

ys.index

RangeIndex(start=0, stop=5, step=1)

We can access the individual elements of the series

by specifying an index label inside square brackets.

The first element in the series is at index 0,

so we access it as follows:

ys[0]

2.0

We can select a range of elements from the series using the slice notation inside the square brackets.

ys[0:3]

0 2.0

1 1.0

2 1.5

Name: y, dtype: float64

The slice notation 0:3 refers to the list of indices [0,1,2].

The result of ys[0:3] is a new series

that contains a subset of the original series

that contains the first three elements of ys.

The values attributes returns all the values stored in the series as a NumPy array.

ys.values

array([2. , 1. , 1.5, 2. , 1.5])

Series calculations#

Series have methods for performing common calculations.

For example,

the method .count() counts the number of values in the series.

ys.count()

5

The method .value_counts() counts the number of times each value occurs in the series.

ys.value_counts()

y

2.0 2

1.5 2

1.0 1

Name: count, dtype: int64

You can perform arithmetic operations like +, -, *, /, ** with series.

For example,

we can calculate the squared y-value plus 1 for each player

using the following code.

ys**2 + 1

0 5.00

1 2.00

2 3.25

3 5.00

4 3.25

Name: y, dtype: float64

We can also apply arbitrary numpy functions to series.

For example,

here is how we can compute the square root of the y-values.

import numpy as np

np.sqrt(ys)

0 1.414214

1 1.000000

2 1.224745

3 1.414214

4 1.224745

Name: y, dtype: float64

The method .sum() computes the sum of the values in the series.

ys.sum()

8.0

We can calculate the arithmetic mean \(\overline{y} = \frac{1}{5}\sum y_i\)

of the values in the series ys by calling its .mean() method.

ys.mean() # == ys.sum() / ys.count()

1.6

Series have numerous other methods for computing summary statistics

like .min(), .max(), .median(), .std(), etc.

The following table lists commonly used statistics method available on series.

Method name |

Descriptions |

Series |

DataFrame |

|---|---|---|---|

|

count of non-null values |

✓ |

✓ |

|

mean (average) |

✓ |

✓ |

|

median |

✓ |

✓ |

|

standard deviation |

✓ |

✓ |

|

variance |

✓ |

✓ |

|

skewness |

✓ |

✓ |

|

kurtosis |

✓ |

✓ |

|

minimum value |

✓ |

✓ |

|

maximum value |

✓ |

✓ |

|

index label of the minimum |

✓ |

✓ |

|

index label of the maximum |

✓ |

✓ |

|

quantile function |

✓ |

✓ |

|

mode |

✓ |

✓ |

|

sum |

✓ |

✓ |

|

product |

✓ |

✓ |

|

correlation |

✓ |

✓ |

|

covariance |

✓ |

✓ |

|

ranks |

✓ |

✓ |

The .quantile(q) method can be used to compute quartiles (use q multiple of 0.25)

and percentiles (use q multiple of 0.01).

The same methods are actually available on Pandas DataFrame objects.

For example,

we can compute the mean of all the numeric columns in the data frame df

by calling its .mean() method.

df.mean(numeric_only=True)

x 2.0

y 1.6

level 2.4

dtype: float64

We used the option numeric_only=True to avoid computing the mean of the team column,

which is not numeric.

The results show the mean of the x, y, and level columns packaged as a Pandas series.

Pandas also provides two methods

that allow us to compute several statistics at once.

Use the .aggregate(<list>) method to compute

multiple statistics specified as a list.

ys.aggregate(["count", "sum", "mean"])

count 5.0

sum 8.0

mean 1.6

Name: y, dtype: float64

The method .describe() computes a descriptive summary

that consists the standard descriptive statistics including

the mean,

the standard deviation,

and the five-number summary (min, Q1, Q2, Q2, max).

ys.describe()

count 5.00000

mean 1.60000

std 0.41833

min 1.00000

25% 1.50000

50% 1.50000

75% 2.00000

max 2.00000

Name: y, dtype: float64

Creating Pandas series from Python lists#

We sometimes create Pandas Series objects from Python lists in order to benefit

all the calculation and aggregation methods available for series objects.

For example,

the code below creates a Pandas series

from a Python list of three numbers then computes their mean,

variance, and standard deviation.

s = pd.Series([5, 10, 15])

s

0 5

1 10

2 15

dtype: int64

s.aggregate(["mean", "var", "std"])

mean 10.0

var 25.0

std 5.0

dtype: float64

Series exercises#

Exercise 3#

TODO

Exercise 4#

TODO

Sorting, grouping, and aggregation#

Sorting and ranking#

We can sort the rows of the data frame based on the values of the column <col>

by calling the method .sort_values(<col>).

For example,

here is how we can sort the data frame by df by the team column.

df.sort_values("level")

| x | y | team | level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 2.0 | 1.5 | a | 1 |

| 1 | 1.5 | 1.0 | a | 2 |

| 0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | a | 3 |

| 3 | 2.5 | 2.0 | b | 3 |

| 4 | 3.0 | 1.5 | b | 3 |

The default behaviour of .sort_values() is to sort the values in ascending order.

We can use the option ascending=False to sort values in descending order.

Note the index in the sorted data frame is now out of order.

since the rows order is now based on the level column,

and not based on their index labels.

If we want the re-index the data frame,

we can call the method .reset_index(drop=True).

df.sort_values("level").reset_index(drop=True)

| x | y | team | level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2.0 | 1.5 | a | 1 |

| 1 | 1.5 | 1.0 | a | 2 |

| 2 | 1.0 | 2.0 | a | 3 |

| 3 | 2.5 | 2.0 | b | 3 |

| 4 | 3.0 | 1.5 | b | 3 |

We can sort by multiple columns using the syntax .sort_values(["<col1>","<col2>"]),

which will sort the rows based the values of the column <col1> first then by <col2>.

For example,

to sort the data frame df by y then by x,

we would use the code df.sort_values(["y","x"]).

Ranking values#

We can obtain the sort-order of values in a data frame

by calling the .rank() method.

The rank of an element in a series tells us the position it appears in when the list is sorted.

Here is how to obtain the ranks of the y-values in the data frame df.

df["y"].rank(ascending=True)

0 4.5

1 1.0

2 2.5

3 4.5

4 2.5

Name: y, dtype: float64

This result tells us that value at index 1 is the smallest (first rank in ascending order).

The value 1.5 appears both at index 2 and 4 so we have a tie.

The default method for dealing with ties,

is to assign the average of the two ranks to both values:

we assign the rank 2.5 to both of them (the average between second and third rank).

The last two values are also tied,

so we assign rank 4.5 to both of them.

You can obtain different way to handle ties

by passing the method option when calling .rank().

Group by and aggregation#

A common calculation we need to perform in statistics

is to compare different groups of observations,

where the grouping is determined by the values in one of the columns.

The Pandas method .groupby() is used for this purpose.

For example,

we can group the observations in the data frame df by the value of the team variable using the following code.

df.groupby("team")

<pandas.core.groupby.generic.DataFrameGroupBy object at 0x7fa67072f550>

The result of calling the .groupby("team") method is a DataFrameGroupBy object

that contains the subsets of the data frame,

which correspond to the different values of the team variable.

The .groupby("mean") method starts

a parallel computation on the two subsets of rows:

the rows of the players from team a (df[df["team"]=="a"])

and rows of the players from team b (df[df["team"]=="b"]).

We can use the DataFrameGroupBy object to do further selection of variables and perform computations.

For example,

to compute the mean value of the x variable within the two groups,

we run the following code.

df.groupby("team")["y"].mean()

team

a 1.50

b 1.75

Name: y, dtype: float64

The result is a series containing the mean for the two groups.

The first row contains the value df[df["team"]=="a"]["y"].mean().

The second row’s value is df[df["team"]=="b"]["y"].mean().

Note the result is a series indexed by the values of the team variable (the team labels a and b).

We often call the .aggregate() method after the goupyby() method

to compute multiple statistics for the two groups.

For example,

to compute the count, the sum, and the mean value in each group

we use the following code.

df.groupby("team")["y"].aggregate(["count", "sum", "mean"])

| count | sum | mean | |

|---|---|---|---|

| team | |||

| a | 3 | 4.5 | 1.50 |

| b | 2 | 3.5 | 1.75 |

The result is a data frame

whose rows correspond to values of the group-by variable team,

and whose columns are the statistics we wanted to calculate.

Sidenote 1: Pandas method chaining#

The groupby example we saw in the previous section

illustrates the “method chaining” pattern,

which is used often in Pandas calculations.

We can “chain” together any number of Pandas methods

to perform complicated data selection and aggregation operations.

We start with the data frame df,

call its .goupyby() method,

select the y column using the square brackets ["y"],

then call the method .aggregate() on the result.

This is “chain” includes contains two methods,

but it is common to chain together three or more methods.

This ability to carry out data manipulations using a sequence of simple method applications

is one of the main benefits of using Pandas for data processing.

Method chaining operations work because Pandas Series, DataFrame,

and GroupBy objects all offer the same methods,

so the output of one calculation can be fed into the next.

Sidenote 2: Line-continuation strategies#

When using method chaining,

the command chains tend to become very long

and often don’t fit on a single line of input.

We can split Pandas expressions on multiple lines

using the Python line-continuation character \ (backslash),

as shown in the code example below.

df.groupby("team")["y"] \

.aggregate(["sum", "count", "mean"])

| sum | count | mean | |

|---|---|---|---|

| team | |||

| a | 4.5 | 3 | 1.50 |

| b | 3.5 | 2 | 1.75 |

The result of this code cell

is identical to the result we saw above,

however writing the code on two lines using the line-continuation character \

makes the operations are easier to read.

It is customary (but not required)

to indent the second line by a few spaces so the dots line up.

The indentation gives a visual appearance of a “bullet list”

of operation we apply to a data frame.

Another way to get the benefits of multi-line commands is to wrap the entire expression in parentheses.

(df

.groupby("team")["y"]

.aggregate(["sum", "count", "mean"])

)

| sum | count | mean | |

|---|---|---|---|

| team | |||

| a | 4.5 | 3 | 1.50 |

| b | 3.5 | 2 | 1.75 |

The result is identical to the result we obtained earlier.

This works because we’re allowed to wrap any Python expression in parentheses without changing its value.

We do this wrapping

because newlines are ignored inside parentheses,

so we’re allowed to break the expression onto multiple lines

without the need to add the character \ at the end of each line.

Don’t worry too much about the line-continuation and parentheses tricks for multi-line expressions. Most of the Pandas expressions you’ll see in this tutorial will fit on a single line, but I wanted to show you some multi-line expressions, so you won’t be wondering what is going on if you see it.

Counting values#

We’re often interested in the counts (frequencies)

of different values that occur in a particular column.

The .value_counts() can do this counting for us.

For example,

here is how we can count the number of players on each team.

df["team"].value_counts()

team

a 3

b 2

Name: count, dtype: int64

The is sometimes called a one-way table or a frequency table.

We can also count combinations of values,

which is called a two-way table.

We can obtain a two-way table y calling the Pandas function pd.crosstab

and specifying which variable we want to use for the index

and which variable we want to use as the columns of the resulting table.

pd.crosstab(index=df["team"],

columns=df["level"])

| level | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| team | |||

| a | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| b | 0 | 0 | 2 |

See Section 1.3.4 in the book,

for additional examples of the pd.crosstab function,

including different use cases of the options margin and normalize.

Using pivot_table for aggregation#

The .pivot_table(...) method produces a spreadsheet-style pivot table

that shows aggregated values, grouped into rows and columns that correspond to categorical columns in the data.

To produce the pivot table must specify:

values: the column to be aggregatedaggfunc: the function used to aggregate the valuesindex: the variable to group by for the pivot table rowscolumns: the variable to group by for the pivot table columns

For example,

the following code produces a pivot table

that display the average y coordinates,

for different teams (rows) and different levels (columns).

df.pivot_table(values="y",

aggfunc="mean",

index="team",

columns="level")

| level | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| team | |||

| a | 1.5 | 1.0 | 2.00 |

| b | NaN | NaN | 1.75 |

Sorting and aggregation exercises#

Exercise 5#

TODO

Exercise 6#

TODO

Data transformations#

Pandas provides dozens of methods for modifying the shape, the index, the columns, and the data types of data frames. Below is a list of common data transformations that you’re likely to encounter when preparing datasets for statistical analysis.

Renaming the column names of a data frame.

Reshaping and restructuring the way the data is organized.

Imputation: filling in missing values based on the surrounding data or a fixed constant.

Merging data from multiple sources.

Filtering to select the subset of the data we’re interested in.

Splitting up columns that contain multiple values.

Data cleaning procedures for identifying and correcting bad data. Data cleaning procedures include dealing with missing values, outliers, coding errors, duplicate observations, and other inconsistencies in the data.

In this section, we’ll show examples of the most common data frame transformations, and defer the data cleaning and outlier detection topics until the next section.

Adding new columns#

We can add a new column to a data frame by assigning data to a new column name as shown below.

df_with_xy = df.copy()

df_with_xy["xy"] = df["x"] * df["y"]

df_with_xy

| x | y | team | level | xy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | a | 3 | 2.0 |

| 1 | 1.5 | 1.0 | a | 2 | 1.5 |

| 2 | 2.0 | 1.5 | a | 1 | 3.0 |

| 3 | 2.5 | 2.0 | b | 3 | 5.0 |

| 4 | 3.0 | 1.5 | b | 3 | 4.5 |

The first line makes a copy of the data frame df

and saves it as a new variable called df_with_xy.

The second line computes the product of the x and y columns from the original df

and assigns the result to a new column named xy in df_with_xy.

We then display the modified data frame df_with_xy

to show the presence the additional column.

Avoiding in-place modifications#

The code example above follows best practices for variable naming:

it uses a different variable name for the modified data frame.

The new variable name df_with_xy

makes it clear this is a modified data frame

and not the same as the original df,

which remains unchanged.

Following this naming convention

makes your code easier to reason about

and avoids many kinds of confusion.

This convention is particularly important in notebook environments,

where code cells can be executed out of order.

Suppose we didn’t follow the convention,

and instead added the column xy to the original df.

In other words,

we’re modifying the data frame df without changing its name.

In this case,

we would need to keep track of which “version” of df

we’re working with in each code cell.

In all the earlier code cells,

the data frame df had columns ["x", "y", "team", "level"],

while later on df has columns ["x", "y", "team", "level", "xy"].

Keeping track of different “versions” of df adds unnecessary cognitive load,

so it’s best if we can avoid it:

use different names for different objects!

The good news is that most of the Pandas transformation methods

do not modify data frames,

but instead return a new data frame,

so you don’t have to manually do the .copy() operation.

You just have to remember to save the transformed version of the data frame as a new variable.

The assign method#

The .assign() method is another way to add new columns to a data frame.

df_with_xy = df.assign(xy = df["x"] * df["y"])

The .assign() method returns a new data frame without modifying the original df.

We save the result to a new variable df_with_xy,

so the end result

is the same as the data frame df_with_xy

that we obtained earlier using the copy-then-modify approach.

The main reason for using the .assign() method

is because it allows us to perform multiple transformations at once

by using the method chaining pattern.

The following example shows how we can perform four different transformation

to the data frame df in a single statement.

df.assign(xy = df["x"] * df["y"]) \

.assign(z = 1) \

.assign(r = np.sqrt(df["x"]**2 + df["y"]**2)) \

.assign(team = df["team"].str.upper())

| x | y | team | level | xy | z | r | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | A | 3 | 2.0 | 1 | 2.236068 |

| 1 | 1.5 | 1.0 | A | 2 | 1.5 | 1 | 1.802776 |

| 2 | 2.0 | 1.5 | A | 1 | 3.0 | 1 | 2.500000 |

| 3 | 2.5 | 2.0 | B | 3 | 5.0 | 1 | 3.201562 |

| 4 | 3.0 | 1.5 | B | 3 | 4.5 | 1 | 3.354102 |

The effect of the first .assign() operation

is to add the new column xy that contains the product of x and y values.

The second operation adds a new constant column z equal to 1.

The third operation adds the column r

computed from the formula \(r = \sqrt{x^2 + y^2}\),

which is the distance between the point with coordinates \((x,y)\) and the origin.

Note we used the function np.sqrt from the NumPy module

to perform the square root operation.

The last assignment operation

transforms the values in the team column to uppercase.

The apply method#

The .apply() method allows you to apply a function

to every row or every column in the data frame.

The following example shows how

we can perform four transformations

by applying a function on each row of the data frame.

def four_ops(row):

row["xy"] = row["x"] * row["y"]

row["z"] = 1

row["r"] = np.sqrt(row["x"]**2 + row["y"]**2)

row["team"] = row["team"].upper()

return row

df.apply(four_ops, axis=1)

| x | y | team | level | xy | z | r | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | A | 3 | 2.0 | 1 | 2.236068 |

| 1 | 1.5 | 1.0 | A | 2 | 1.5 | 1 | 1.802776 |

| 2 | 2.0 | 1.5 | A | 1 | 3.0 | 1 | 2.500000 |

| 3 | 2.5 | 2.0 | B | 3 | 5.0 | 1 | 3.201562 |

| 4 | 3.0 | 1.5 | B | 3 | 4.5 | 1 | 3.354102 |

Dropping rows and and columns#

Pandas provides several methods for removing rows and columns of a data frame.

For example,

to drop the first (index 0), third (index 2), and fifth (index 4) rows of the data frame df

we can use the .drop() method and pass in the list of indices to remove as the index argument.

df.drop(index=[0,2,4])

| x | y | team | level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.5 | 1.0 | a | 2 |

| 3 | 2.5 | 2.0 | b | 3 |

The result is a new data frame

that contains only the second row (index 1)

and the fourth row (index 3).

To remove columns from a data frame,

use .drop() method with the columns option.

Here is the code to delete the column level.

df.drop(columns=["level"])

| x | y | team | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | a |

| 1 | 1.5 | 1.0 | a |

| 2 | 2.0 | 1.5 | a |

| 3 | 2.5 | 2.0 | b |

| 4 | 3.0 | 1.5 | b |

The result is a new data frame that no longer has the level column.

An alternative way to obtain the same result

is to select the three columns

that we want to keep using the code df[["x", "y", "team"]].

Pandas also provides the methods .dropna() for removing rows that contain missing values

and .drop_duplicates() for removing rows that contain duplicate data.

We’ll learn more about these methods in the section on data cleaning later on.

Renaming columns and values#

To change the column names of a data frame,

we can use the .rename() method and pass in to the columns argument

a Python dictionary of the replacements we want to make.

For example,

the code below renames the columns names team and level to uppercase.

df.rename(columns={"team":"TEAM", "level":"LEVEL"})

| x | y | TEAM | LEVEL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | a | 3 |

| 1 | 1.5 | 1.0 | a | 2 |

| 2 | 2.0 | 1.5 | a | 1 |

| 3 | 2.5 | 2.0 | b | 3 |

| 4 | 3.0 | 1.5 | b | 3 |

The dictionary {"team":"TEAM", "level":"LEVEL"} specifies the old:new replacement pairs

for the column names.

To rename the values in the data frame,

we can use the .replace() method,

passing in a Python dictionary of replacements

that we want to perform on the values in each column.

For example,

here is the code for replacing the values in the team column to uppercase letters.

team_mapping = {"a":"A", "b":"B"}

df.replace({"team":team_mapping})

| x | y | team | level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | A | 3 |

| 1 | 1.5 | 1.0 | A | 2 |

| 2 | 2.0 | 1.5 | A | 1 |

| 3 | 2.5 | 2.0 | B | 3 |

| 4 | 3.0 | 1.5 | B | 3 |

The dictionary {"a":"A", "b":"B"} specifies the old:new replacement pairs

specifies the old:new replacement pairs for the values.

Reshaping data frames#

One of the most common transformations we need to do with data frames, is to convert them from “wide” format to “long” format. Data tables in “wide” format contain multiple observations in each row, with the column headers conveying some information about the observations in the different columns. The code example below shows a sample data frame with the viewership numbers for a TV show organized by season (rows) and by episode (columns).

views_data = {

"season": ["Season 1", "Season 2"],

"Episode 1": [1000, 10000],

"Episode 2": [2000, 20000],

"Episode 3": [3000, 30000],

}

tvwide = pd.DataFrame(views_data)

tvwide

| season | Episode 1 | Episode 2 | Episode 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Season 1 | 1000 | 2000 | 3000 |

| 1 | Season 2 | 10000 | 20000 | 30000 |

This organizational structure is very commonly used

for data entered manually into in a spreadsheet,

since it’s easy for humans to interpret values based on the columns they appear in.

However,

working with datasets complicates data selection, grouping, and filtering operations.

Data scientists and statisticians prefer to work with “long” format datasets,

where each row corresponds to a single observation,

and each column corresponds to a single variable,

like the minimal dataset we discussed earlier.

The Pandas operation for converting “wide” data to “long” data is called melt,

which is an analogy to melting a wide block of ice into a vertical stream of water.

The method .melt() requires several arguments

to specify how to treat each of the columns in the input data frame,

and the names we want to assign to the columns in the output data frame.

Let’s look at the code example first,

and explain the arguments after.

tvlong = tvwide.melt(id_vars=["season"],

var_name="episode",

value_name="views")

tvlong

| season | episode | views | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Season 1 | Episode 1 | 1000 |

| 1 | Season 2 | Episode 1 | 10000 |

| 2 | Season 1 | Episode 2 | 2000 |

| 3 | Season 2 | Episode 2 | 20000 |

| 4 | Season 1 | Episode 3 | 3000 |

| 5 | Season 2 | Episode 3 | 30000 |

The argument id_vars specifies the column that contain identifier variables for each row,

which is the column season in the data frame tvwide.

All other columns are treated as “value variables”

that identify the properties of all the values in that column.

In the above example,

the values variables are the columns Episode 1, Episode 2, and Episode 3.

The argument var_name allows us to choose the name for the variable

that is represented in the different columns,

which we set to the descriptive name episode.

Finally,

the value_name argument determines name of the value column in the melted data frame,

which we set to views since this what the numbers represent.

The result tvlong has six rows,

one for each observation in the original data frame tvwide.

Each row in tvlong corresponds to one episode of the TV show,

and each column corresponds to a different variable for that episode

(the season, the episode, and the number of views).

The rows in the data frame tvlong

have are ordered strangely after the melt operation.

It would make more sense

for the all the Season 1 episodes to appear first,

followed by Season 2.

We can fix the sort order

by calling the .sort_values() method

and specifying the column names by which we want the data to be sorted.

tvlong.sort_values(by=["season", "episode"]) \

.reset_index(drop=True)

| season | episode | views | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Season 1 | Episode 1 | 1000 |

| 1 | Season 1 | Episode 2 | 2000 |

| 2 | Season 1 | Episode 3 | 3000 |

| 3 | Season 2 | Episode 1 | 10000 |

| 4 | Season 2 | Episode 2 | 20000 |

| 5 | Season 2 | Episode 3 | 30000 |

The data is now sorted by season first then by episode,

which is the natural order for this data.

The also called the method .reset_index()

to re-index the rows using the sequential numbering

according to the new sort order.

Tidy data#

The concept of tidy data is a convention for structuring datasets that makes them easy to work with. A tidy dataset has the following characteristics:

Each column contains the values for one variable.

Each row contains the values for one observation.

Each data cell contains a single value.

The data frame tvlong we saw in the previous has all three characteristics:

each column contains a different variable,

each row contains the data for one episode,

and each cell contains one piece of information.

In contrast,

the data frame tvwide is not tidy data,

since each row contains the information from three episodes.

An example of a cell that contains multiple values

would be the case where age and gender are stored together,

where the code 32F would indicate a 32 year old female.

This is not tidy and will complicate all selection and filtering procedures.

It would be preferable to store age and sex as two separate columns,

and put the values 32 and F in the corresponding columns.

The tidy data convention for organizing datasets

makes it easy to select subsets of the data based on values of different columns,

and perform arbitrary transformations, groupings, and aggregations.

For example,

the data frame tvlong allows us filter and group views

based on any combination of the season and episode variables.

Another reason for working with tidy data is that it makes data visualization easier. We can create advanced Seaborn plots by simply mapping column names to different attributes of the graphs like x- and y-positions, colors, sizes, and marker types. We’ll learn more about this in the Seaborn tutorial (Appendix E).

Perhaps the biggest reason behind the popularity of the tidy data convention is that it standardizes the formatting of datasets. When starting to work on a new tidy dataset, you don’t waste any time trying to understand how the data is structured, since you know all the variables are in different columns, and each row corresponds to a different observation.

“Tidy datasets are all alike, but every messy dataset is messy in its own way.” —Hadley Wickham

Indeed, whenever encountering datasets that are don’t have the tidy data characteristics, data scientist will first spend the tidying it up.

String methods#

You can use the .str prefix to access string manipulation methods like

.str.split(), .str.startswith(), .str.strip(), etc.

Any operation that you can perform on a Python string,

you can also perform on Pandas series by calling the appropriate str-method.

For example,

suppose we have a data frame ppl_df

with a column agesex that contain the age and sex information as a single string.

ppl_df = pd.DataFrame({

"names": ["Jane", "John", "Jill"],

"agesex": ["32F", "20M", "21F"]

})

ppl_df

| names | agesex | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Jane | 32F |

| 1 | John | 20M |

| 2 | Jill | 21F |

We can split the agesex column into separate age with sex columns

using the following code.

ages = ppl_df["agesex"].str[0:-1].astype(int)

sexes = ppl_df["agesex"].str[-1]

ppl_df2 = ppl_df.drop(columns=["agesex"])

ppl_df2["age"] = ages

ppl_df2["sex"] = sexes

ppl_df2

| names | age | sex | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Jane | 32 | F |

| 1 | John | 20 | M |

| 2 | Jill | 21 | F |

Another way to extract the two values would

be to use the .str.extract() method

with a regular expression .str.extract("(?P<age>\\d*)(?P<sex>[MF])").

Merging data frames#

We sometimes need to combine data from multiple data frames.

For example,

suppose we’re given a data frame levels_info with additional info about

the game characters’ life and power depending their level in the game.

# levels_info table (one row per level)

levels_info = pd.DataFrame({

"lvl": [1, 2, 3],

"life": [100, 200, 300],

"power": [10, 20, 30],

})

levels_info

| lvl | life | power | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 100 | 10 |

| 1 | 2 | 200 | 20 |

| 2 | 3 | 300 | 30 |

We can add this information

to the players data frame df

by calling the method pd.merge.

We link the information in the two data frames

by matching between the level column in df

and the lvl column in the levels_info data frame.

pd.merge(left=df, right=levels_info,

left_on="level", right_on="lvl")

| x | y | team | level | lvl | life | power | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | a | 3 | 3 | 300 | 30 |

| 1 | 1.5 | 1.0 | a | 2 | 2 | 200 | 20 |

| 2 | 2.0 | 1.5 | a | 1 | 1 | 100 | 10 |

| 3 | 2.5 | 2.0 | b | 3 | 3 | 300 | 30 |

| 4 | 3.0 | 1.5 | b | 3 | 3 | 300 | 30 |

Another method for combining data frames include df.join()

which uses the index to matches the rows based data frames.

Concatenating data frames#

Sometimes we need to extend a data frame by adding a new row of observations.

We can use the pd.concat function to concatenate two data frames,

as shown below.

new_df = pd.DataFrame([{"x":2, "y":3, "team":"b", "level":2}])

pd.concat([df,new_df], axis="index", ignore_index=True)

| x | y | team | level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | a | 3 |

| 1 | 1.5 | 1.0 | a | 2 |

| 2 | 2.0 | 1.5 | a | 1 |

| 3 | 2.5 | 2.0 | b | 3 |

| 4 | 3.0 | 1.5 | b | 3 |

| 5 | 2.0 | 3.0 | b | 2 |

Data type conversions#

The method .astype allows us to transform a column into a different data type.

For example,

the level column in the data frame df has data type int64,

which stores integers as 64 bits.

Using int64 allows us to store very large values,

but this is excessive given the largest number we store in this column is 3.

df["level"].dtype

dtype('int64')

If we convert the column level to data type int8,

it will take up eight times less space.

df["level"].astype(np.int8)

0 3

1 2

2 1

3 3

4 3

Name: level, dtype: int8

One-hot and dummy coding for categorical variables#

We often need to convert categorical variables into numerical values

to use them in statistics and machine learning models.

The key idea is to represent the different values as separate columns

that contain indicator variables.

An indicator variable \(\texttt{var}_{\texttt{val}}\)

is a variable that is equal to \(1\)

when the categorical variable var has the value val,

else is equal to \(0\).

The one-hot encoding of a categorical variable with \(K\) possible values

requires \(K\) different columns,

named after the value they encode.

The Pandas function pd.get_dummies() performs this encoding.

For example,

the one-hot encoding of the variable team looks like this:

pd.get_dummies(df["team"],

dtype=int,

prefix="team")

| team_a | team_b | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 1 |

| 4 | 0 | 1 |

The column team_a contains indicator variable \(\texttt{team}_{\texttt{a}}\),

which is 1 whenever the team variable has value a, and is 0 otherwise.

The column team_b contains the indicator variable \(\texttt{team}_{\texttt{b}}\).

The name one-hot encoding comes from the observation there is only a single 1 per row.

A commonly used variant of the one-hot encoding scheme is dummy coding,

which treats the first value of a categorical variable as the “reference” value,

and uses indicator variables to represent the other levels.

When using dummy coding,

a categorical variable with \(K\) possible values

gets encoded into \(K-1\) columns.

Passing the option drop_first to the pd.get_dummies() function.

pd.get_dummies(df["team"],

dtype=int,

prefix="team",

drop_first=True)

| team_b | |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 |

| 3 | 1 |

| 4 | 1 |

The rows where team_b is 0 indicate the variable team has its reference value,

which is a.

In statistics,

we use this dummy coding

when fitting linear regression models with categorical predictors,

which is discussed in Section 4.4.

Transpose#

The transpose transformation flips a data frame through the diagonal, turning the rows into columns, and columns into rows.

dfT = df.transpose()

dfT

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | 1.0 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 3.0 |

| y | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 1.5 |

| team | a | a | a | b | b |

| level | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

After the transpose operation,

the rows index df.index becomes the columns index dfT.columns,

while the columns index df.columns

becomes the rows index dfT.index.

I hope the above examples gave you some idea of the transformations that we can apply to data frames. Try solving the exercises to practice your new skills.

Transformation exercises#

Exercise 7#

TODO

Exercise 8#

TODO

Data cleaning#

The term data cleaning describes the various procedures that we do to prepare datasets for statistical analysis. Data cleaning steps include fixing typos and coding errors, removing duplicate observations, detecting outliers, and correcting inconsistencies in the data. These data cleaning steps are essential for the validity of all the subsequent analysis you might perform on this data. We need to make sure that the statistical calculations will not “choke” on the data, or produce erroneous results.

We can conceptualize data cleaning as starting from a “raw” dataset and transforming it into a “clean” dataset through a sequence operations like renaming variables, replacing values, changing data types, dropping duplicates, filtering outliers, etc. Data cleaning is often the most time consuming part of any data job, and it is definitely not glamorous work, but you must get used to it. The only datasets that don’t require cleaning are the ones created for educational purposes. Most real-world datasets you download from the internet or use at work will needs some cleaning before they can be used. Luckily, Pandas provides lots of helper functions that make data cleaning a breeze.

Standardize categorical values#

A very common problem that occurs for categorical variables is the use of multiple codes to represent the same concept. Consider the following series containing what-type-of-pet-is-it data in which “dog” is encoded using four different labels.

pets = pd.Series(["D", "dog", "Dog", "doggo"])

pets

0 D

1 dog

2 Dog

3 doggo

dtype: object

This type of inconsistent encoding will cause lots of trouble down the line.

For example,

performing a .groupby() operation on this variable will result in four different groups,

even though all these pets are dogs.

We can fix this encoding problem by standardizing on a single code for representing dogs and replacing all other values with the standardized code, as shown below.

dogsubs = {"D":"dog", "Dog":"dog", "doggo":"dog"}

pets.replace(dogsubs)

0 dog

1 dog

2 dog

3 dog

dtype: object

The method .value_counts() is helpful for detecting coding errors and inconsistencies.

Looking at the counts of how many times each value occurs can help us notice exceptional values,

near-duplicates, and other problems with categorical variables.

pets.replace(dogsubs).value_counts()

dog 4

Name: count, dtype: int64

Exercise 9: cleaning the cats data#

Write the code to standardize all the cat labels to be cat.

# Instructions: clean the cat labels in the following series

pets2 = pd.Series(["cat", "dog", "Cat", "CAT"])

pets2

0 cat

1 dog

2 Cat

3 CAT

dtype: object

Number formatting errors#

The text string "1.2" corresponds to the number \(1.2\) (a float).

We can do the conversion from text string to floating point number as follows.

float("1.2")

1.2

When loading data,

Pandas will automatically recognize numerical expression like this and load them into columns of type float.

There are some common number formatting problems you need to watch out for.

Many languages use the comma is the decimal separator instead of a decimal point,

so the number 1.2 might be written as the text string "1,2",

which will not be recognized as a float.

float("1,2")

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ValueError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[93], line 1

----> 1 float("1,2")

ValueError: could not convert string to float: '1,2'

To fix this issue, we replace the comma character in the string with a period character as follows.

"1,2".replace(",", ".")

'1.2'

Another example of a problematic numeric value is "1. 2",

which is not a valid float because of the extra space.

We can fix this by getting rid of the space using "1. 2".replace(" ", "").

Let’s see how to perform this kind of string manipulations when working with data stored in a series or a data frame.

rawns = pd.Series(["1.2", "1,3", "1. 4"])

rawns

0 1.2

1 1,3

2 1. 4

dtype: object

The series rawns contains strings with correct and incorrect formatting.

Note the series rawns has dtype (data type) of object,

which is what Pandas uses for strings.

Let’s try to convert this series to a numeric values (floats).

We can do this by calling the method .astype() as shown below.

# uncomment to see the ERROR

# rawns.astype(float)

Calling the method .astype(float)

is essentially the same as calling float on each of the values in the series.

We get an error since the string "1,3" is not a valid float.

We can perform the string replacements on the data series rawns using the “str-methods” as shown below.

rawns.str.replace(",", ".") \

.str.replace(" ", "") \

.astype(float)

0 1.2

1 1.3

2 1.4

dtype: float64

After performing the replacements of commas to periods and removing unwanted spaces,

the method .astype(float) succeeds.

Note the method we used in the above example is the string method .str.replace()

and not general .replace() method.

Other types of data that might have format inconsistencies include dates, times, addresses, and postal codes. We need to watch out when processing these types of data, and make sure all the data is in a consistent format before starting the statistical analysis.

Dealing with missing values#

Real-world datasets often suffer from missing values

because of mistakes in the data collection process.

Missing values in Pandas are indicated with the special symbol NaN (Not a Number),

or sometimes using the symbol <NA> (Not Available).

In Python, the absence of a value corresponds to the value None.

The term null value is a synonym for missing value.

You can think of NaN values as empty slots.

To illustrate some examples of dealing with missing values,

we’ll load the dataset located at datasets/raw/minimal.csv,

which has several “holes” in it.

rawdf = pd.read_csv("datasets/raw/minimal.csv")

rawdf

| x | y | team | level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | a | 3.0 |

| 1 | 1.5 | 1.0 | a | 2.0 |

| 2 | 2.0 | 1.5 | a | 1.0 |

| 3 | 1.5 | 1.5 | a | NaN |

| 4 | 2.5 | 2.0 | b | 3.0 |

| 5 | 3.0 | 1.5 | b | 3.0 |

| 6 | 11.0 | NaN | NaN | 2.0 |

The data frame rawdf contains the same data we worked on previously

plus additional rows with “problematic” values that we need to deal with.

The missing values are indicated by the NaN symbol.

Specifically,

the rows with index 3 is missing the level variable,

and row 6 is missing the values for the y and team variables.

We can call the .info() method

to get an idea of the number of missing values in the data frame.

rawdf.info()

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 7 entries, 0 to 6

Data columns (total 4 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 x 7 non-null float64

1 y 6 non-null float64

2 team 6 non-null object

3 level 6 non-null float64

dtypes: float64(3), object(1)

memory usage: 352.0+ bytes

The data frame has a total of 7 rows,

but the columns level, y, and team have only 6 non-null values,

which tells us these columns contain one missing value each.

We can use the method .isna() to get a complete picture of all the values that are missing (not available).

rawdf.isna()

| x | y | team | level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | False | False | False | False |

| 1 | False | False | False | False |

| 2 | False | False | False | False |

| 3 | False | False | False | True |

| 4 | False | False | False | False |

| 5 | False | False | False | False |

| 6 | False | True | True | False |

The locations in the above data frame that contain the value True

correspond to the missing values in the data frame rawdf.

We can summarize the information about missing values, by computing the row-sum of the above data frame, which tells us count of the missing values for each variable.

rawdf.isna().sum(axis="rows")

x 0

y 1

team 1

level 1

dtype: int64

We can also compute the column-sum to count the number of missing values in each row.

rawdf.isna().sum(axis="columns")

0 0

1 0

2 0

3 1

4 0

5 0

6 2

dtype: int64

The most common way of dealing with missing values is to exclude them from the dataset,

by dropping all rows that contain missing values.

The method .dropna() filters out any rows that contain null values

and returns a new “clean” data frame with no NaNs.

rawdf.dropna()

| x | y | team | level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | a | 3.0 |

| 1 | 1.5 | 1.0 | a | 2.0 |

| 2 | 2.0 | 1.5 | a | 1.0 |

| 4 | 2.5 | 2.0 | b | 3.0 |

| 5 | 3.0 | 1.5 | b | 3.0 |

We can provide various option subset to the .dropna() method to focus on specific columns.

For example,

to drop only rows that contain null values in the columns x or y,

we would use the code rawdf.dropna(subset=["x","y"]).

Using the subset option makes sense if we

plan analyze only these columns,

and missing values in the other columns will not be a problem.

Another approach for dealing with missing values is to use imputation, which is the process of “filling in” values based on our best guess of what the missing values might have been. One common approaches for filling in missing numeric values is to use the mean of the other values in that column.

fill_values = {

"y": rawdf["y"].mean()

}

rawdf.fillna(value=fill_values)

| x | y | team | level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.0 | 2.000000 | a | 3.0 |

| 1 | 1.5 | 1.000000 | a | 2.0 |

| 2 | 2.0 | 1.500000 | a | 1.0 |

| 3 | 1.5 | 1.500000 | a | NaN |

| 4 | 2.5 | 2.000000 | b | 3.0 |

| 5 | 3.0 | 1.500000 | b | 3.0 |

| 6 | 11.0 | 1.583333 | NaN | 2.0 |

Imputation is a tricky process, since it changes the data, which can affect the statistical analysis performed on the data. It would be much better if you go back to the data source to find what the missing values are, instead of making arbitrary choice like the mean.

Removing duplicates#

The method .drop_duplicates() can be used to remove redundant rows

that contain the same data.

Duplicate rows can appear as a result of repeated data entry,

or due to overlaps that occur when merging datasets.

Identifying and removing outliers#

Outliers are data values that are much larger or much smaller than other values. A mistake in the data collection process like measurement instrument malfunctions, measurements of the wrong subject, or typos can produce extreme observations in a dataset that don’t make sense. For example, if we intend to study the weights of different dog breeds but somehow end up including a grizzly bear in the measurements, your dogs dataset will the value 600 kg for a dog’s weight. This extreme weight outlier tells you some mistake has occurred, since such a weight measurement is impossible for a dog.

It’s important for you to know if your data contains outliers before you start your analysis on this data, otherwise the presence of outliers might “break” the statistical inference machinery, and lead you to biased or erroneous results.

Sometimes we can correct outliers by repeating the measurement. For example, if the data was manually transcribed from a paper notebook, we could consult the original notebook to find the correct value. Other times, we can’t fix the faulty observations, so our only option is to exclude it (drop it) from the dataset.

Let’s look at an example dataset that contains an outlier. The data sample \(\texttt{xs} = [1,2,3,4,5,6,50]\) consists of seven values, one of which is much much larger than the others.

xs = pd.Series([1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 50], name="x")

xs

0 1

1 2

2 3

3 4

4 5

5 6

6 50

Name: x, dtype: int64

We can clearly see that the value 50 is an outlier in this case,

but the task may not be so easy for larger datasets

with hundreds or thousands of observations.

Why outliers are problematic#

Outliers can have undue leverage on the value of certain statistics

and may produce misleading analysis results.

Statistics like the mean, variance, and standard deviation

are affected by the presence of outliers.

For example,

let’s compute the mean (average value)

and the standard deviation (dispersion from the mean)

of the sample xs.

xs.mean(), xs.std()

(10.142857142857142, 17.65812911408012)

These values are very misleading: they give us the wrong impression about the centre of the data distribution and how spread out it is. In reality, the first six values are small numbers, but the presence of the large outlier \(50\) makes the mean and the standard deviation appear much larger.

If we remove the outlier \(50\), the mean of the standard deviation of the remaining values \([1,2,3,4,5,6]\) is much smaller.

xs[0:6].mean(), xs[0:6].std()

(3.5, 1.8708286933869707)

These summary statistics are much more representative of the data. The mean value \(3.5\) is a good single-number description for the “centre” of the data points, and the standard deviation of \(1.87\) also gives us a good idea of the dispersion of the data points.

Any subsequent statistical analyses we might perform with this data will benefit from these more accurate summary statistics we calculated after removing the outlier.

Criteria for identifying outliers#

We’ll now describe some procedures for detecting outliers. There are several criteria we can use to identify outliers:

Visual inspection is probably the simplest way to detect outliers. Simply plot the data as a strip plot or scatter plot, and look for values that don’t seem to fit with the rest.

The Tukey criterion considers any value that is more than 1.5 the interquartile range, \(\mathbf{IQR} = \mathbf{Q}_3 - \mathbf{Q}_1\), away from the outer quartiles of the data to be an outlier. This is the criterion we used when drawing Tukey box-plots in Section 1.3.

The \(z\)-score criterion allows us to identify values that are very far away from the mean, using a multiple of the standard deviation as the measure of distance.

We’ll now show how to apply these criteria to the data sample xs.

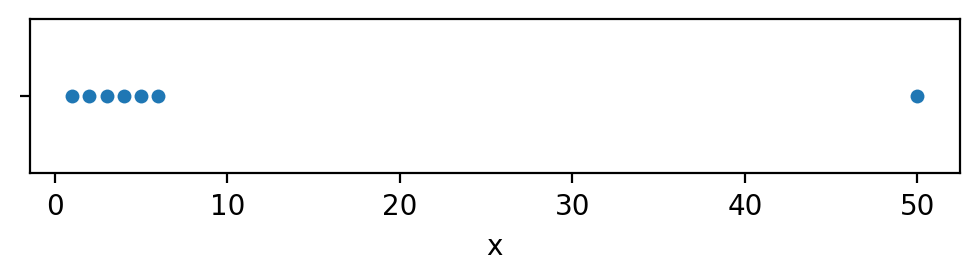

Visual inspection of the data#

A strip plot of the data sample xs

can help us simply “see” outliers if they are present.

Here is how to use the Seaborn function sns.stripplot to plot the data.

import matplotlib.pylab as plt

import seaborn as sns

plt.figure(figsize=(6,1))

sns.stripplot(x=xs, jitter=0);

# # FIGURES ONLY

# import matplotlib.pylab as plt

# import seaborn as sns

# with plt.rc_context({"figure.figsize":(6,1)}):

# ax = sns.stripplot(x=xs, jitter=0);

# ax.set_xlabel(None)

We clearly see one of these is not like the others.

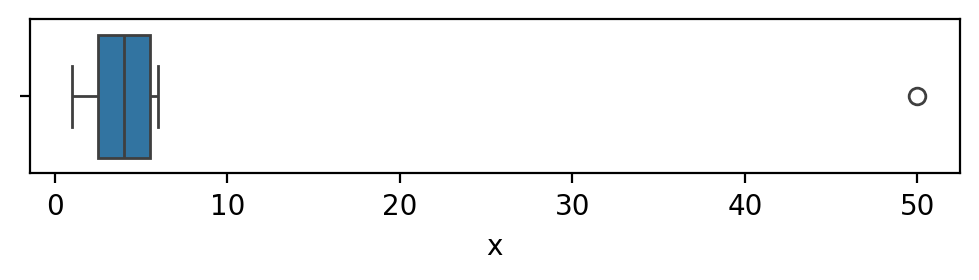

Tukey outliers#

The Tukey box plot is a standard data visualization plot

produced from the quartiles of dataset,

The rectangular “box” goes from \(\mathbf{Q}_{1}\) to \(\mathbf{Q}_{3}\).

The width of this box is the interquartile range \(\mathbf{IQR}\).

A vertical line is placed in the \(\mathbf{Q}_{2}\) (the median).

Tukey box plots give special attention to the display of outliers,

which are represented as individual circles.

The lines extending from the box are called whiskers

and represent the range of the data excluding outliers.

We can use the Seaborn function sns.boxplot to obtain a Tukey box plot of the data xs.

# # FIGURES ONLY

# with plt.rc_context({"figure.figsize":(6,1)}):

# ax = sns.boxplot(x=xs)

# ax.set_xlabel(None)

The Tukey plot uses the distance \(1.5 \cdot \mathbf{IQR}\)

away from the quartiles box as the criterion for identifying outliers.

In other words,

any values that fall outside the interval

\([\mathbf{Q}_{1} - 1.5 \cdot \mathbf{IQR}, \mathbf{Q}_{3} + 1.5 \cdot \mathbf{IQR}]\)

is an outlier.

The outlier at \(x=50\) is displayed as circle,

and clearly stands out.

The whiskers in the box plot range from the smallest and largest values within the interval

\([\mathbf{Q}_{1} - 1.5 \cdot \mathbf{IQR}, \mathbf{Q}_{3} + 1.5 \cdot \mathbf{IQR}]\).

The right whisker in the above figure is placed at \(x=6\)

which is the largest non-outlier value in xs.

Let’s reproduce the calculations that Seaborn performed to identify the outliers in the Tukey box plot using Pandas methods. We start by compute the first quartile \(\mathbf{Q}_{1}\), the third quartiles \(\mathbf{Q}_{3}\), and the interquartile range \(\mathbf{IQR}\).

Q1, Q3 = xs.quantile([0.25, 0.75])

IQR = Q3 - Q1

Q1, Q3, IQR

(2.5, 5.5, 3.0)

We can now calculate the cutoff values for Tukey outlier criterion, which is 1.5 times the interquartile range away from the outer quartiles.

[Q1 - 1.5*IQR, Q3 + 1.5*IQR]

[-2.0, 10.0]

The Tukey plot identifies values outside the interval \([-2,10]\) as outliers.

In words,

values smaller than \(-2\) or greater than \(10\)

are “unusual” for the data sample xs.

We can build a mask that selects values that fit the Tukey criteria

by combining the two conditions xs < -2 and xs > 10

using the bitwise OR operator |.

tukey_outliers = (xs < -2.0) | (xs > 10.0)

tukey_outliers

0 False

1 False

2 False

3 False

4 False

5 False

6 True

Name: x, dtype: bool

The tukey_outliers series

tells us which values in the series xs are outliers.

We can use this mask to filter out the outliers,

as we’ll show later in this section.

Detecting outliers using z-scores#

Another way to detect extreme values

is to identify values that are multiple standard deviations away from the mean.

Given the data \([x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_n]\),

we compute the \(z\)-scores \([z_1, z_2, \ldots, z_n]\),

using the formula \(z_i = \frac{x_i - \overline{\texttt{xs}}}{s_{\texttt{xs}}}\),

where \(\overline{\texttt{xs}} = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n x_{i} =\) xs.mean() is the same mean,

and \(s_{\texttt{xs}} = \sqrt{\frac{1}{n-1}\sum_{i=1}^{n}(x_i - \overline{\texttt{xs}} )^2 } =\) xs.std()

is the sample standard deviation.

The \(z\)-score \(z_i\) of an observation \(x_i\)

tells you where \(x_i\) sits relative to the mean \(\overline{\texttt{xs}}\).

xbar = xs.mean()

xstd = xs.std()

zscores = (xs - xbar) / xstd

zscores

0 -0.517770

1 -0.461139

2 -0.404508

3 -0.347877

4 -0.291246

5 -0.234615

6 2.257155

Name: x, dtype: float64

We can identify outliers by their unusually large \(z\)-scores. For example, we could check which values are more than two standard deviations away from the mean, by selecting \(z\)-scores that are less than \(-2\) or greater than \(2\).

zscore_outliers = (zscores < -2) | (zscores > 2)

zscore_outliers

0 False

1 False

2 False

3 False

4 False

5 False

6 True

Name: x, dtype: bool

We see that the \(z\)-scores method also identifies \(50\) as an outlier.

Removing outliers#

We can use the tukey_outliers or the zscore_outliers criteria

to filter out the outliers.

We’ll actually invert the tukey_outliers mask

using the Python NOT operator ~

to obtain a mask for all the values which are not outliers,

and use this mask to select only the subset of values that are not outliers.